Art and wine have been linked for centuries as partners in celebrating the human needs to be creative and to find pleasure. But more recently, the term “appreciation” as applied to wine and art has changed from being one of veneration to one of realizing financial gains, as the two have journeyed hand in hand deeper into secondary markets that now threaten to overwhelm primary markets.

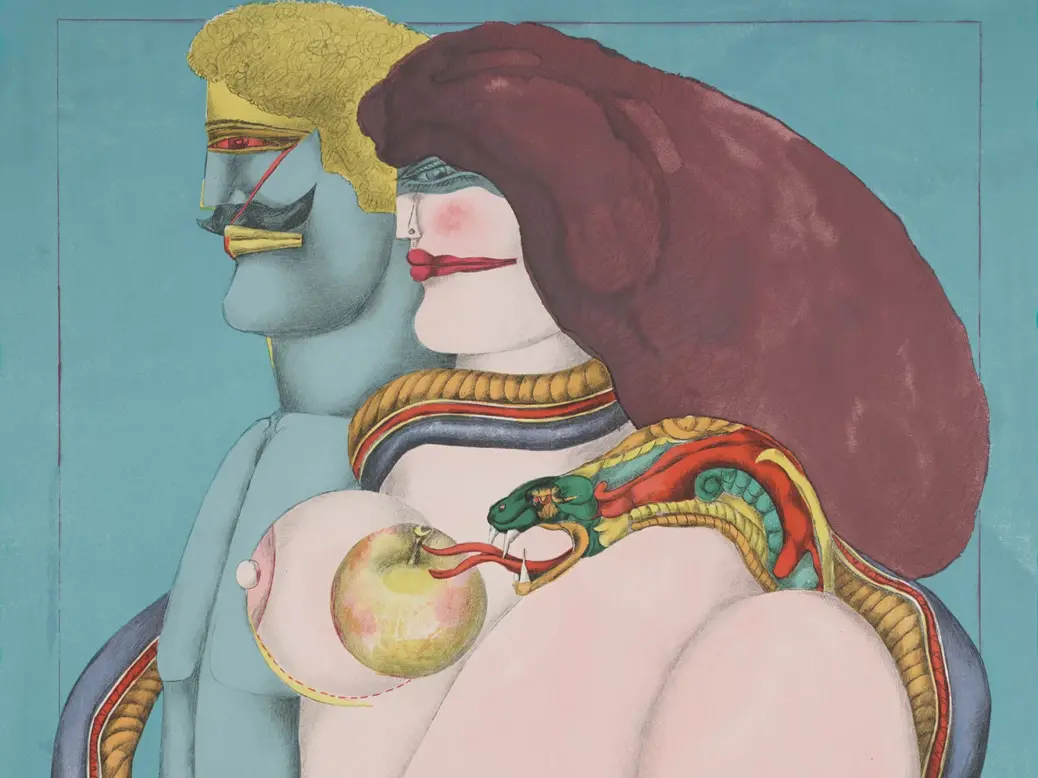

Every couple needs an origin story, and has there ever been a more Hollywood-style “meet cute” saga than that of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden? (Sadly, theirs wasn’t exactly a happy ending, however, so there go the film rights.) It might be amusing, then, to use this universal metaphor to consider another creative couple who have been intimately paired for millennia by poets, playwrights, and even critics—wine and art—and see how their origin story might adapt to their own garden.

We would begin by considering which one of our two was Adam and which was Eve. And where does the snake fit in? And which of the two companions took the first bite of the apple? And was the apple an erotic red, as it is historically depicted, or was it actually a lush green—as in cash? Finally, might it now be time to reexamine—and bring up to date—this enduring relationship between wine and art?

Much has been written about the eons-long creative coupling between the two—art and wine, wine and art—often in exalted terms. One reason is that both activities were among primitive humans’ first attempts at creativity that went beyond what was needed to survive and evolve. Instead, art and wine were early appeals to our aesthetic nature—something to enjoy after the labors of daily survival. It isn’t surprising, then, that the two quickly intertwined. Grapes and wine have long appeared linked in primitive drawings and paintings, and winemakers have added decorations to their product by creating beautiful images on their casks, jugs, and bottles that added appeal to the liquid inside. The two early became a pair.

In time, another line of thought appeared, as visual art graduated from being mere illustrations—a craft—into lifelike painted images on canvases and frescos, as well as graven, sculpted figures. Should fine winemaking, then, follow art’s path and the finest of wines be declared an art and the winemakers who created them be deemed artists and not mere craftsmen?

Yet little has been written about another shared path, primarily forged within the past century, where fine art and fine wine have been treasured not only for their inherent value, something to be praised in poetry and prose, but increasingly as instruments of investment—a road that has extended beyond their adoration by buyers, a path in which appreciation as a term of veneration has been replaced by, or at least supplemented by, appreciation as a term for the monetary gains resulting from shrewd investment.

There are differences, of course. Most of us think of wine as something to be consumed—and it is. Wine critics taste a wine, write a description of it, and generally value it with a number—in theory to guide others who can afford the wine to buy it and consume it. Similarly, fine art has its vaunted critics, though they are less numbers-oriented than their vinous compatriots, and their collective judgments help validate an individual’s or a museum’s decision to purchase a particular artist’s work of visual art.

Unlike wine, visual art can’t (or shouldn’t) be physically consumed, and generally there is only one tangible output of each creative act, though there may be prints and various other means of legal reproduction. Traditionally, once purchased or commissioned, the painting or sculpture stayed with the buyer or his or her family until they grew tired of it or circumstances forced them or their creditors to sell it—not always at a profit.

The growth of the secondary market, however, has changed all that. When fine wine or fine art is first purchased today—on the primary market—the duration of its ownership has been shortened in anticipation of its resale on the secondary market, or short-circuited completely.

In fact, the argument could—should—be made that the secondary market for the most-valued fine wine and fine art is now more important than the primary market, much the way that the best athletes compete only briefly as amateurs before becoming professionals, a reversal of a century ago when true amateurism reigned. And while individual investors in fine art and fine wine may truly appreciate them in the traditional sense, their goal in buying wine or art is no longer solely for the pleasure it gives but also for the profit it may eventually yield as an investment. And it is in this secondary market that visual art and fine wine are more similar than they are different.

Think not? Then consider who buys each, how they buy it, how what they buy is valued, how its value is tracked over time, how its authenticity is validated (or not) as it is bought, sold, bought, than sold again; how it is stored, how it is seldom available for the collective public’s eye or palate, how… The list goes on and on.

Thus the need to revisit the creation myth of the relationship between wine and art, one in which the nature of “naked lust” is redefined, where the apple indeed is green and not red, and in which the snake, whatever it represents, isn’t necessarily the one to blame. But that is another aspect of the myth that needs to be reexamined: Is it necessary today to attribute blame to someone or something to begin with?

The formation of the secondary market

Historically, the secondary market for all goods has not been a sexy one. After all, most things that have been manufactured, sold, used, and often discarded by the original purchaser and then come up for resale have lost considerable value, often battered and out of fashion or replaced by something more efficient. Moreover, the purchasers of these used goods are often those who can’t afford, or are too “cheap,” to buy something new. Even today, the venues where these used goods are placed for resale are hardly glamorous: second-hand stores, used car lots, pawn shops, flea markets, bazaars, yard sales, the Internet…

Historically, when the need arose to resell efficiently a collection of multiple goods, a different kind of institution came into existence—the auction house, where a person skilled in oratory sells things individually or in lots to a crowd of bargain-hunters. (It should be noted that, historically, auctions have also sold people, a despicable practice that continued even in many “civilized” countries well into the 19th century. The first recorded auction was in Babylon in 500 bc and sold brides to interested husbands. In the centuries since, conquered people were routinely auctioned into slavery.)

But it was only a couple of centuries ago that auctions and the secondary market took on increased importance as a growing number of wealthier people and institutions began to collect items whose value might actually increase with time or, at a minimum, were still quite expensive and desirable even if they had lost some value. In short, the growth of the secondary market blossomed when it discovered luxury goods.

Importantly, at this stage, art and wine began to distinguish themselves from other luxury goods—though certainly not exclusively—for two reasons. First, they both attracted the attention of the news media and thus encouraged public discussion: Readers could scoff at the millions being paid for “modern” art, especially non-representational works that “even my children could paint better,” and also debated the question of how could a bottle of wine be resold for hundreds of times more money than a perfectly drinkable one? The second reason was wine and art shared the same audience: More people of means collected art or wine (and often both) than did watches, Empire furniture, or automobiles.

Thus, wine and art became the high-profile darlings of the luxury secondary market. Moreover, when one of them adopted an innovative marketing tactic or tool, the other usually quickly followed suit.

While private agents and dealers were—and still are—important in buying and selling luxury collections, it was auction houses that were key in promoting the growth of the secondary market. And two London houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s, became the drivers. Sotheby’s, founded in 1744, was first established as an auctioneer for book collections, and Christie’s, founded in 1766, started as an art house. Before too long, fine wine quickly followed as luxury items to go under the hammer at both firms.

The secondary market, phase 2

World War II changed everything in the world order. European empires fell. The United States, which always had a few millionaire collectors who flocked to Europe the way the British elite once tromped to Greece and Rome, became hugely prosperous as it doubled and tripled its numbers of wealthy people—mainly men—who were able to exhibit their wealth and cultivation by collecting fine things.

Art had always been at the top of collectors’ shopping lists, but a couple of decades after the war, wine, after going through a rough patch, had an opportunity to take its place alongside. “I guess the economics were at their worst [in Bordeaux] in the mid-1960s, with the tiny crop of 1961 and the write-off years of 1963, ’65, and ’68,” writer, wine merchant, and wine producer Steven Spurrier remembered in our email conversation in December 2020, less than three months before his death. “I bought ten barrels of 1966 sur souches [before the harvest] in June 1966 and did very well, the system being banned after that.”

Then things changed quickly and drastically for the better. “As the market and the economy picked up in the 1970s, the châteaux had more funds,” Spurrier continued, “but we all know it was the ‘Parker’ vintage of 1982 that changed everything, with high quality and high quantity. From that moment on, the [first growths] and seconds began to hold stock back and make a smaller amount of the grand vin.”

Spurrier himself, of course, also had a large hand in bringing American wealth into a wine market then concentrated in Europe, even if it wasn’t totally intentional. The tasting he organized in 1976—the Judgment of Paris, in which French wine experts preferred California Cabernets and Chardonnays to their own—blossomed into a burst of American pride. The later-disgraced President Nixon, a lover of fine wine, took bottles of Schramsberg California Blanc de Blancs with him in 1972 for his famous opening-of-China toast with Zhou Enlai.

For the rest of the past century, interest in wine surged in the Unites States at all levels, and American baby boomers—those born shortly after the war—became avid wine collectors, buying Bordeaux futures and the best of California wines. Plus, it’s always more fun to play an international game—and to bet on its future—if you also have a home team that is competitive.

Of course, Robert Parker had other effects on wine collection and commerce. His 100-point scoring system made it easy to compare the critical value of wines, the way one would items listed on a stock market or currency exchange. He also—and this is no exaggeration—changed the actual taste of fine red table wine.

In most cases up to this point, art had always been the innovator, and wine the follower. But in this instance, wine was the market innovator of the two. Wine growers who may have preferred the leaner, more structured wines of France and Italy suddenly began making fruit-forward, higher-alcohol wines, particularly those who retained the consulting services of Michel Rolland, who knew what Parker liked and how to make it. (“I know which type of wine I like, and that is with density, concentration,” Rolland told me in a 2009 interview. “I don’t like wine really very light and too acidic.”) More than one winemaker said, in so many words, “If I want to get higher scores and higher prices, I have to make big, fruity wines the way Parker likes them.”

In the late 1990s, the Parker phenomenon lessened, particularly as younger wine consumers became as interested in diversity of drinking experiences as they were in points. Some observers even predicted the fine-wine boom would end with the bursting in 1999 of the dot-com bubble.

But instead, two fresh forces entered the marketplace and began to drive a third wave, one that drew the practices of fine wine and fine art even closer together in an economic sense. One was a new tranche of collectors in Russia, China, and other Asian countries. The other was the rise of digital technology, especially the Internet.

The secondary market, phase 3

James Miles admits he knew little about wine in the late 1990s, but due to an early career as a stockbroker he did understand exchanges. “I came across four cases of 1995 Lafite,” he said in a recent conversation, “and two years later they were worth two or three times more than what I paid for them. It gave me a creeping curiosity, and I wanted to see what was going on. It struck me how similar wines were to the equities market: Both are fragmented by products and by the numbers of players in the market.”

So, in 2000, James Miles and Justin Gibbs launched Liv-ex, the London-based, business-to-business wine exchange that currently has 560 members spread across 43 countries. With the aid of technology—especially the Internet—Miles says, “We introduced real-time prices, accurate price indices, and a democratization” to the buying and selling of wine on the secondary market. “Before, maybe five guys knew what the real prices of wines were.”

While there is not an art exchange comparable to Liv-ex, there are very many similarities in how wine and art sales are categorized. Wine sales are generally viewed hierarchically from region to winery to that winery’s individual labels (including vintage, of course); and art is similarly tracked according to artistic style, the artist, and individual work by that artist. Because wine is a multi-unit consumable, however, wine tracking tends to separate the primary and secondary markets in reporting financial activity more than the art market does.

In both the wine and art worlds, though, the development of digital communications and tracking technology, along with the loosening of the traditional customs of trading and of some regulations, have changed every aspect of wine and art commerce in the secondary market, including:

the global expansion of both markets,

how wine and art are sold internationally,

how both auctions and agent sales to consumers are conducted,

how prices are established and tracked,

how the provenance and authenticity of goods are guaranteed,

how and where the “goods” are stored,

how wine and art are protected against loss or theft, and

who the buyers are.

Beginning with global markets, it is well documented how Internet technology, the expansion of existing marketing systems, and global politics made the sale of fine wine and fine art truly international. The fall of the Soviet Union and the rise of wealthy oligarchs there, plus the experimentation with market capitalism creating a wealthy class in China—however brief each proves to be—caused the expansion of auction houses and specialized merchants into each of those regions.

The economic results of this now truly international market, even accounting for a two-year world pandemic, are impressive. Sotheby’s, for example, had record sales in both art and wine, with its wine turnover at $132 million, over half of which was in Asia, and bidders from 56 countries. While overall wine-sale figures combining primary and secondary markets is not reliably available, Dr Clare McAndrew, in her annual report The Art Market, in partnership with UBS, estimates worldwide art and antique sales reached a record $6.5 billion in 2021, with 43 percent going to the US market.

Developments in sales technology for art and wine are also advancing hand in hand. Key among these are the growth of real-time, 24/7 online sales, which went from novelty to economic driver during the pandemic. Art dealers continue to open additional showrooms worldwide, and the Asian outposts for auctions houses are no longer merely outposts. In wine, La Place de Bordeaux, with its more than 400 négociants, has driven growth in recent years by expanding from being only a seller of great wines from Bordeaux, to representing fine wineries in the United States, Europe, Australia, and South America.

In a 2017 interview, as these were beginning to blossom, négociant Allan Sichel told me, “To take on a new client, [négociants] have to be reasonably confident that they will be able to sell the wine and generate a reasonable profit. The more attractive the offer [reputation and selling price], the keener the négociant will be.”

Part of that attractiveness depends on how wine critics value a fine wine. “Like it or not, fine wine is just another asset class,” says Allen Meadows, whose influential reviews of Burgundies in particular are published in his Burghound newsletter. And, Meadows notes, it’s not just investment groups and corporations that buy wine as financial assets. “Today, few, if any, buyers of the rarest of the rare are not intensely aware of how rare they are but just how valuable they are,” he says, citing the trend of buying a case, drinking six bottles, and selling the other six.

As Liv-ex’s Wilson points out, being able to track sales in real time is important, noting that, not that many years ago, buying or selling wines on the secondary market might involve a shop owner making multiple phone calls and consulting a variety of journals to establish a price. “They made their money on the inefficiency of the system.”

And once wines or art are purchased, many never see the insides of the homes of the people who have purchased them. (One could argue that both wine and art are natural “homebodies,” that fine wine is at its most vibrant with food and friends at the family table—as it was originally intended and is sometimes still practiced—rather than being analyzed in a sterile tasting room. Similarly, a great painting is at its most vibrant as part of an ensemble of furniture and accessories in a living room, rather than hanging on the sterile walls of an art museum.)

In the United States, there has been a recent proliferation of ultra-modern art and wine storage systems, such as ones owned by Ouvo in New York, Florida, Delaware, and California. In addition to having viewing and event rooms for art and wine collectors, Uovo has an Internet portal through which, says Uovo spokesperson Hannah Gottlieb-Graham, “clients can access their full wine inventory, contact their account manager and make service requests, all from the comfort of their own home. Our in-house photography team can help ensure all aspects of the collection are properly visualized and documented.”

Provenance and authenticity are also critically important on the secondary market, and while older canvases and bottles of wine may still require painfully slow documentation, increasingly both are using built-in verifications systems. “Wine has become much more sophisticated in how to protect against fraud,” with labeling tags, says Jamie Ritchie, Sotheby’s worldwide chairman of wine and spirits.

Similarly, even modest collectors of wine are buying specialized insurance policies as guarantees against theft, vandalism, or natural disasters, as art collectors have long done. “Standalone wine policies cost about 40 to 50 cents for every $100 worth of wine,” says Loretta L Worters of the Insurance Information Institute, so it’s easy for any collector to do the math.

Finally, the profile of collectors has changed in both art and wine. While Ritchie and Miles think investment funds are somewhat cyclical—rising wine prices luring collective investors at a time when other financial returns are flat—there are nevertheless signs that they are growing.

“Requiring just $5,000 to begin investing, we give investors and wine enthusiasts access to over 12 asset classes, including high-quality wine investments, through a single diversified fund that transcends borders,” says Marrisa Morris of the Hedonova hedge fund. “Our unique model makes us a highly sought-after fund, and in just two years, our roster boasts more than 2,000 accredited investors and $92 million in holdings.”

In an April interview with The Drinks Business, Matthew O’Connell, CEO of Bordeaux Index, says wine as a convertible asset investment is attracting younger investors. “When we get feedback from new users about our LiveTrade trading platform, they are very positive about the fact that we offer a clear two-way pricing on all of the wines,” he said. “Not only do they know what we sell it for and what we will buy it back for, but if they invest significant capital in wine, they can easily sell it back to us the next day if desired—which is something that historically has been lacking in the wine market but is a strength of equities.”

Questions and the immediate future

So, where do the wine and art markets go from here? Nothing appears more likely to disrupt both wine and art markets than NFTs (non-fungible tokens) and cryptocurrencies. According to the recent The Art Market report, art-related NFTs expanded over a hundredfold between 2020 and 2021, reaching $2.6 billion in value, mainly on NFT platforms such as Ethereum, Flow, and Ronin. While many of the wine-related NFTs to date have been little more than glorified certificates of sale and sometimes a coupon to wine-related benefits in addition to the bottle(s) of wine, they also guarantee blockchain traceability.

One of the most interesting recent developments in this area is the decision by Domaine du Comte Liger-Belair in Vosne-Romanée to sell its entire 2020 vintage production through NFTs via the new Wokenwine platform. “It is necessary to give confidence back to wine lovers by putting integrity back into traceability and fighting against counterfeits,” Count Louis-Michel Liger-Belair stated in announcing his decision. “Selling wines through NFTs is a way not only to achieve this but also to put the control of the wine authentication in the hands of the wine growers.”

Adding a “wine plus” to offering the wine itself, the use of blockchain traceability and trading in cryptocurrencies will most likely carve out new marketing and distribution channels and add new players to challenge or augment traditional marketing and tracking functions such as auctions, agents, and exchanges.

Second, fine-wine producers are testing the waters for more ways to get a larger share of profits from sales and appreciation. One way is for wineries to employ more delayed-release tranches, thus keeping wine in their cellars for longer periods of time before releasing it many vintages later. As long as market appreciation outweighs the cost of inventory, it is a winning formula.

And unlike with art, producers of fine wines see their profits chipped away by the number of hands it must go through before it reaches consumers, especially in the United States, where wine sales and distribution are highly regulated. “More producers are establishing companies in the US and then using them to sell their imported wines,” Ritchie says.

Finally, the secondary market will continue to grow in importance to the point that it may become the tail that wags the dog. Consider that selling prices to the primary market are mainly driven by a wine’s reputation, both historically and through reviews and ratings of the current vintage. Prices on the secondary market, by contrast, are driven by demand, actual or expected. Although there are some trade-offs both ways, when the exchange and auction prices of a wine or a wine region fall on the secondary market, as is now happening with Bordeaux, it can seriously dampen the release prices of the current vintage and of futures campaigns, regardless of reviews and ratings. And with art, we already know that falling prices at auction will lower the selling price for new works by a living artist—or by a dead one.

As more pure investors, whether as individuals or groups, are attracted to the secondary market, will wine take on even more trappings of the stock and commodities markets, especially the development of various forms of derivatives? It is no surprise that people with wealth and an urge to acquire are often both wine and art collectors, but dual collecting will become less likely if asset investment is the only consideration.

And the critical decision of when to sell is also likely to change. Ritchie likes to quote the “three Ds” of when traditional collections go up for sale: “death, debt, and divorce.” With pure investors, the decision is strictly determined by what the market is doing and what it is expected to do.

Back to the garden

There is no doubt that both art and wine have bitten of the fruit—the lure of the secondary market. With that bite, some of their innocence is gone—and perhaps ours as well. Who took the first bite? Art has always been the bigger and the splashier of the two, so maybe it nibbled first, though wine needed no coaxing. The snake, of course, is the market forces that tempted both wine and art to go for a bigger bite of the spoils.

So, is there a moral here? Some would argue that higher prices at the top make wine and art less available to everyman and everywoman, yet there is plenty of good, affordable wine and art for almost any budget. That answers the primary question in any issue of morality: Is anyone getting hurt? A corollary question is whether the investment-first attitude of the secondary market will harm the primary market, yet that is mainly a question of economics and not morality. If it happens, those most likely to be hurt will be wine and art investors and not those who buy their weekly wine at the supermarket and watercolors from weekend artists in the park.

Miles of Liv-ex, who got into the wine-exchange business with a couple of cases of first-growth Bordeaux, makes an interesting if perhaps rather rhetorical observation. “Today, if I can afford a case of a first growth, then it’s underpriced,” he says. The same could be said of a Basquiat or Bacon.

From an economics and marketing-strategy point of view, watching the fine-art and fine-wine markets today makes for great theater—two elderly stars still in their ascendency still searching for the spotlight. If the performers are no longer the innocents they once were in the Garden of Creation, well, perhaps neither is the audience.

This article was first published in June 2022 in issue 76 of the print edition of The World of Fine Wine.