Chloe Ashton reports on the latest news and views from the world’s fine wine salerooms, as things begin to cool off again.

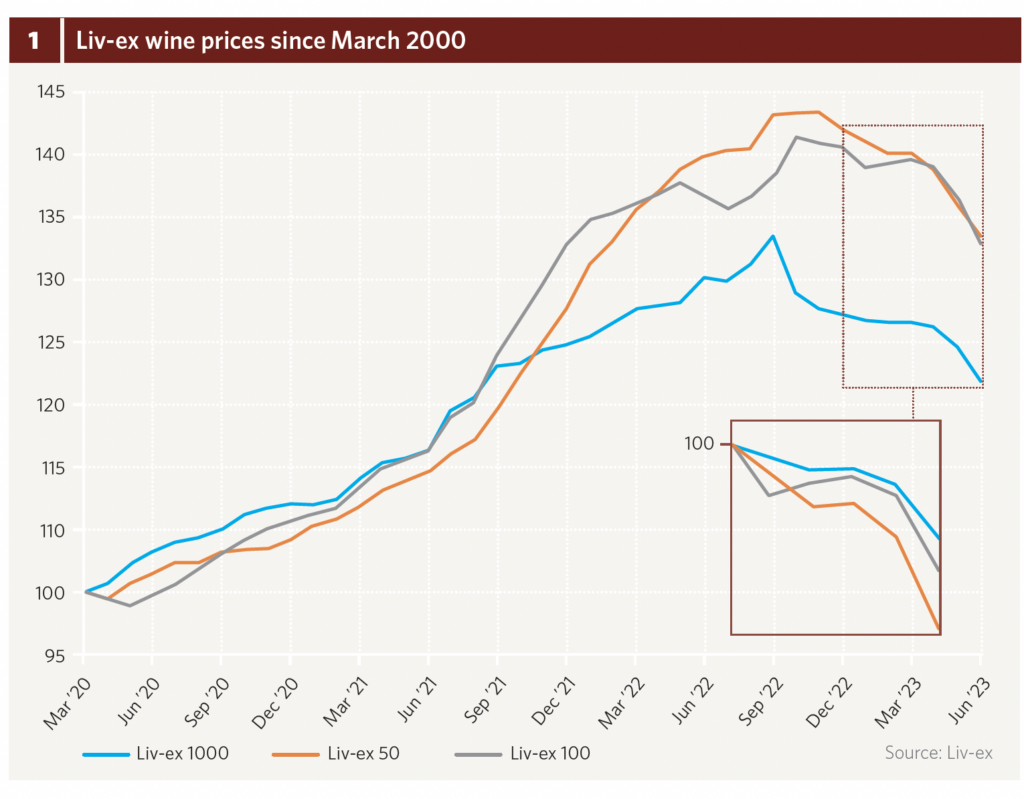

One year ago, fine wine registered a new record: the steepest price climb the market had seen since records began. Over a period of 30 months, from March 2020 until September 2022, Liv-ex’s three main indices rose by an average 38 percent. Since then, market prices have fallen, prompted by global economic jitters as the era of cheap financial lending comes to an end, and worsened by the natural close of an enormous demand cycle from collectors whose cellars are now bursting. Speaking to various members of the global fine-wine trade throughout 2023 thus far, the phrase “market correction” has been employed often, suggesting that price rises incited during the Covid pandemic were unsustainable. Correction or not, the current fine-wine era is likely to be transformational: Brexit threatens the UK’s position as a world trading hub, the baby-boom generation is reaching the end of its buying cycle, and climate change is rewriting the books of what a “normal” vintage looks like. Whatever lies ahead, making predictions (and assumptions) based on what has come before is riskier than it has been in the past.

Fog ahead in the fine-wine market

Indeed, when I asked George Wilmoth, head of sales at leading UK merchant, Justerini & Brooks, where the wine market might be heading in 2023, he deferred his answer: “Ask me again in September,” he said. A quieter market during the summer is usual, but it’s hard to know whether the current cooling-off period will extend into fall and beyond. So far this year, Liv-ex numbers all point toward market deceleration. The platform’s widest measure, and the biggest performer of 2022—the Liv-ex 1,000—dropped 6 percent between January and June this year (fig. 1). Its siblings, the Liv-ex 100 and Liv-ex 50, declined by 3.5 and 3 percent respectively. On the one hand, these are not big numbers relative to financial indices. The S&P 500 dropped 5.8 percent in one month between August and September 2022, finishing last year with a net annual loss of 19 percent. On the other hand, the Liv-ex 1,000’s rate of decline (1.17 percent per month) over the past six months matches exactly the average pace of its unprecedented upward climb from March 2020 through mid-September 2022. They say the faster the climb, the harder the fall, but at least the Bordeaux first-growth index—the Liv-ex 50—provides a cushion to soften the impact. Its journey down in 2023 (so far an average monthly loss of 0.79 percent) is at least slower than its previous rise (of 0.93 percent per month). Commenting on this year’s downward trend, Robbie Stevens, senior broker for Liv-ex reminds me, “The wine market is naturally cyclical.” Indeed, after such a surge, and considering the current context of muted demand, we should probably expect further falls for Liv-ex indices in 2023.

The fourth dimension

Supply-and-demand theory in its purest form is perhaps insufficient to describe wine-collecting cycles. Given the long cellaring periods that great wines require, demand does not equal immediate consumption, and a drop-off in purchases therefore cannot be an accurate measure of consumer interest. Demand can be active and passive—reflected in fine wine’s track record of peaks and troughs, wherein price rises generally indicate an overactive market; during plateaux, however, buyers are consolidating and holding, not necessarily actively trading. Matthew O’Connell, CEO of Bordeaux Index’s LiveTrade platform, appears relaxed about a temporary market downturn. While he admits that “business is slow,” he specifies that it has been more robust in the UK and Europe, while quiet in the US and quieter still in Asia. This “technical lack of activity,” as he puts it, has not skewed LiveTrade transaction prices as much as Liv-ex indices might suggest. “Burgundy’s cult names are still trading at prices similar to last year,” he tells me, albeit with lower frequency. Such market stagnation seems to be universal: Stevens notes that until March this year, merchants remained optimistic that the reopening of China might create room for continued growth, in demand and price elasticity. “[China’s] unlocking has actually had the reverse effect,” he explains, due presumably to distractions caused by the reopening of international travel and the country’s own internal trades taking precedent.

The question over how much a lack of demand can genuinely bring prices down can only be answered through an additional dimension: time. An inactive market only becomes bear when merchants or collectors cannot continue to hold stock until demand picks up again. For the UK wine trade in general, Stevens predicts that trades on the Liv-ex exchange under market prices will increase in July and August, as consumer buying remains quiet and some merchants lose the nerve (or simply the ability) to continue retaining stock. For private collectors, the prior surge in demand combined with today’s choppy economic waters might shake a few bottles out of the fine-wine tree, from those who overshot on their purchases and are now forced to sell. O’Connell nonetheless reassures me that this need—and its consequent contribution to lowering wine prices—remains marginal.

The tortoise and the hare

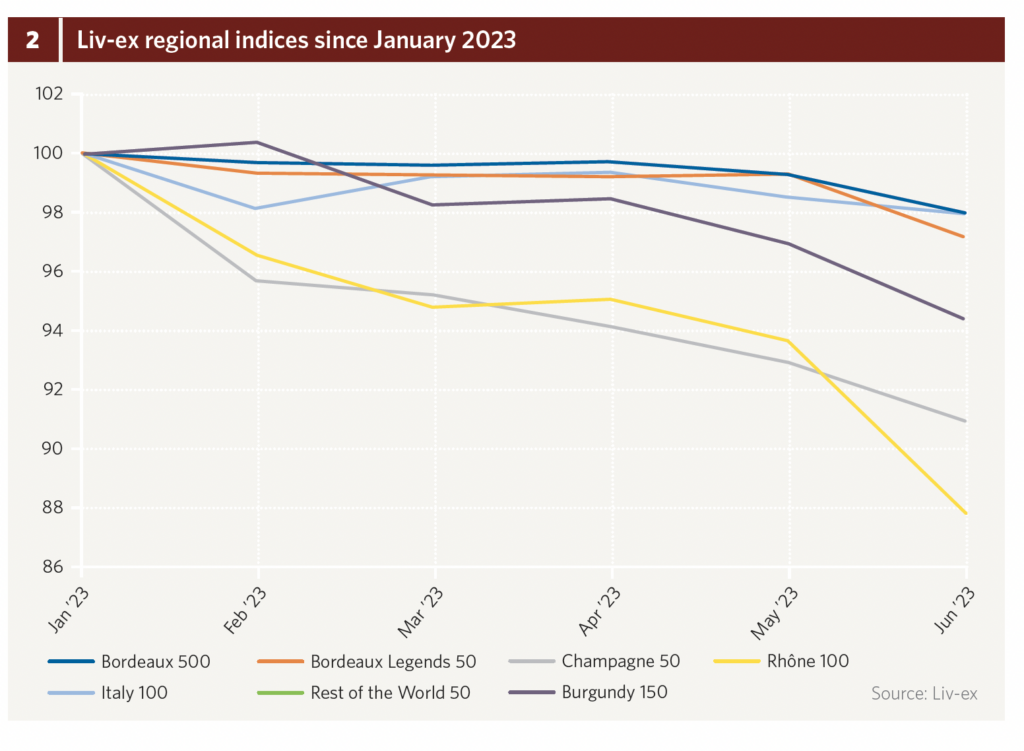

Regionally speaking, the table of relative success has turned in 2023. Liv-ex’s wider Bordeaux measure—the Bordeaux 500—has been the platform’s least worst performer so far this year (losing 2 percent since January 2023). The resilience of Bordeaux in harder times is not new, though O’Connell comments that its performance—in terms of pricing and trading density—could have been better, had this year’s en primeur sales proved successful. He notes that high prices for 2022 not only made for a small campaign, they also “failed to generate the usual enthusiasm and momentum for the region as a whole.” Indeed, despite some trading activity related to recent deliverable vintages, Arthur Coggill, associate director and fine-wine buyer at Goedhuis & Co, tells me, “Our buying director said it was the worst campaign he’d seen in 20 years.” He goes on to note, “The campaign’s poor momentum and misinformed pricing extinguished interest from buyers who were otherwise poised to invest, either because they had set money aside to do so, or because they buy en primeur systematically each year.” Despite this, Bordeaux has seen its market share increase on Liv-ex’s exchange, from 34 percent last year, up to 39 percent as of June 2023. For the small group of collectors forced to liquidate some of their wine holdings, Bordeaux seems to be the first port of call. “It’s certainly not what I would rush to sell, but people always seem to get rid of their Bordeaux first,” observes Wilmoth. He elaborates by explaining, first, that collectors tend to be less emotionally attached to Bordeaux than other regions; and second, that the strong returns observed thus far for Burgundy entice owners to hold these wines closer to the chest. Minute volumes of each cuvée also likely mean that the Burgundy that collectors have acquired will be more difficult to replace in future, whereas mature Bordeaux is still relatively available. Any discounted Burgundy trades on the Liv-ex exchange contributing to the Burgundy 150 index’s losses of 6 percent since the start of 2023 are more strategic; their sellers still earn strong net gains following the index’s recent ascent (70 percent between March 2020 and end 2022), and opportunistic buyers are still poised to snap up ultra-rare stock. The behavior of Liv-ex’s Champagne index appears similar…

Sprint and stall

High trading of Champagnes under the peak prices of 2022—presumably on the part of those cashing in after the unprecedented price rises of the region—have brought Liv-ex’s Champagne 50 down by 9 percent between January and June 2023. O’Connell comments that “Champagne prices have risen so much over the past couple of years, it would almost be weird if they didn’t come down a little.” While he’s confident in Champagne prospects for the long haul (particularly given their solid backing by some of the luxury industry’s biggest players), the picture in the mid-term is perhaps less certain. Wilmoth believes we can expect the index to stall for a while: “The string of mediocre vintages to be released over the next few years is likely to keep prices flat,” he explains. But the worst performer of 2023 thus far has been Liv-ex’s Rhône 100 index. Declining by 12 percent between January and June 2023, similar mechanics as have befallen Bordeaux may be at play: liquidation by trade and private collectors alike, who are perhaps reevaluating the hefty investment in storage and patience required for top Rhône wines to become drinkable. Stevens notes, “The region’s succession of high-quality vintages means buyers will have a lot of Rhône in their cellars after the past decade.” The timing for release of 2021—a subpar vintage—amid fine wine’s current conditions has surely not helped.

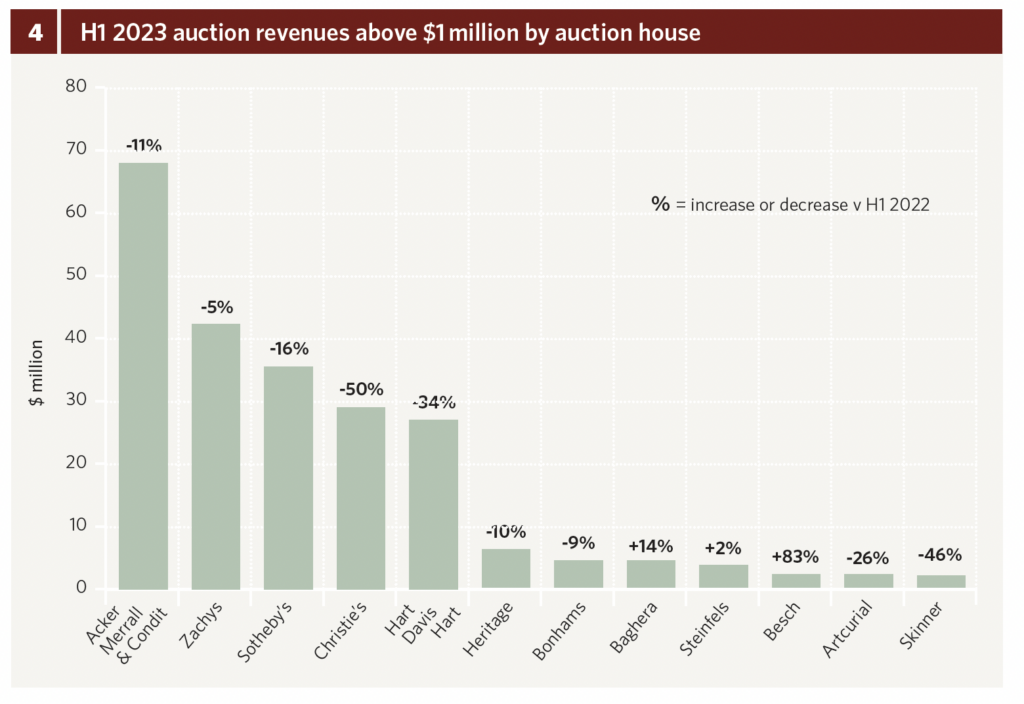

Live and online auction revenues totalled $226 million in the first half of 2023—down 21 percent on last year’s record-breaking H1 (fig. 3). While sales still look buoyant compared to the Covid-stricken results of 2020, this year’s decrease is significant enough to fall below 2019 and 2018 levels—a definitive sign of decline in global demand.

Stable Sam

Indeed, all three major markets—the US, Europe, and Asia—report revenue reductions compared with H1 2022. The US maintains its position as top continent for wine auctions, taking a 57 percent share in sale revenues (equal to $129 million) for the first half of 2023. Its relative stability is also evident, as the market that has lost the least ground when compared to the first half of 2022: American auctions in H1 2023 were down 15 percent in value, whereas Asia—comprising sales in Hong Kong and Singapore—registered a loss of 30 percent (at $67 million). Europe’s auction total for January to June 2023 stands at $30 million, 26 percent down on the same period last year. And while global giants, aka “the big five”—Acker Merrall & Condit, Zachys, Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Hart Davis Hart—still dominate the market, they have all suffered the consequences of muted enthusiasm for active buying of fine wine in 2023 thus far. Acker Merrall & Condit remains the world’s biggest auction house by value, earning $67 million in wine sales in the first half of 2023—a decrease of 11 percent on last year’s H1 achievement (fig. 4). Its compatriot Zachys registers an H1 result of $42 million, closing the gap on its rival with a smaller comparable decrease of 5 percent. Perhaps expectedly, all but three further auction outfits achieving six-month sale totals above $1 million reflect market decline. Those showing growth on the same period last year—Swiss houses Steinfels and Baghera, and Cannes-based Besch—are perhaps testament to the power of micro-markets, since they benefit from respective local (and more loyal) audiences.

Cracks appearing

As for explaining the cause and effect of cracks appearing in the market, opinions are mixed. Charles Antin, head of wine-auction sales at Zachys, maintains a positive outlook on the auction market in 2023. He notes that “blue-chip bottles have retained their high value” and that the “market has proven resistant in the face of uncertain economics.” In contrast, Steinfel’s Marc Fischer shares a different experience: “We clearly see that the interest in very expensive top wines is considerably lower, and prices have come down. In particular, there is almost no more demand for the super-expensive top Burgundies.” He observes that “UK wine merchants were bidding very carefully,” while “interest from Asia is still very strong, and Swiss clients are still very strong bidders.” Across the cultural border from Zurich to Geneva, Baghera’s Julie Carpentier noted a “renewed appetite from collectors around the globe” in Q2 2023. Her colleague and director of Baghera’s Singapore-based arm, Arthur Leclerc, shares his commentary on Asian activity: “The Singaporean wine market has been heading for a sharp price correction since the start of 2023. Wine merchants have large inventories and are retaining—they are therefore not in a buying period. On the other hand, we can count on an ever-increasing number of private buyers and consumers. This is particularly the case in Singapore and Asia in general.” Hope springs for Asia over the long term, as Leclerc notices “the ever-decreasing average age of our buyers.”

Top down

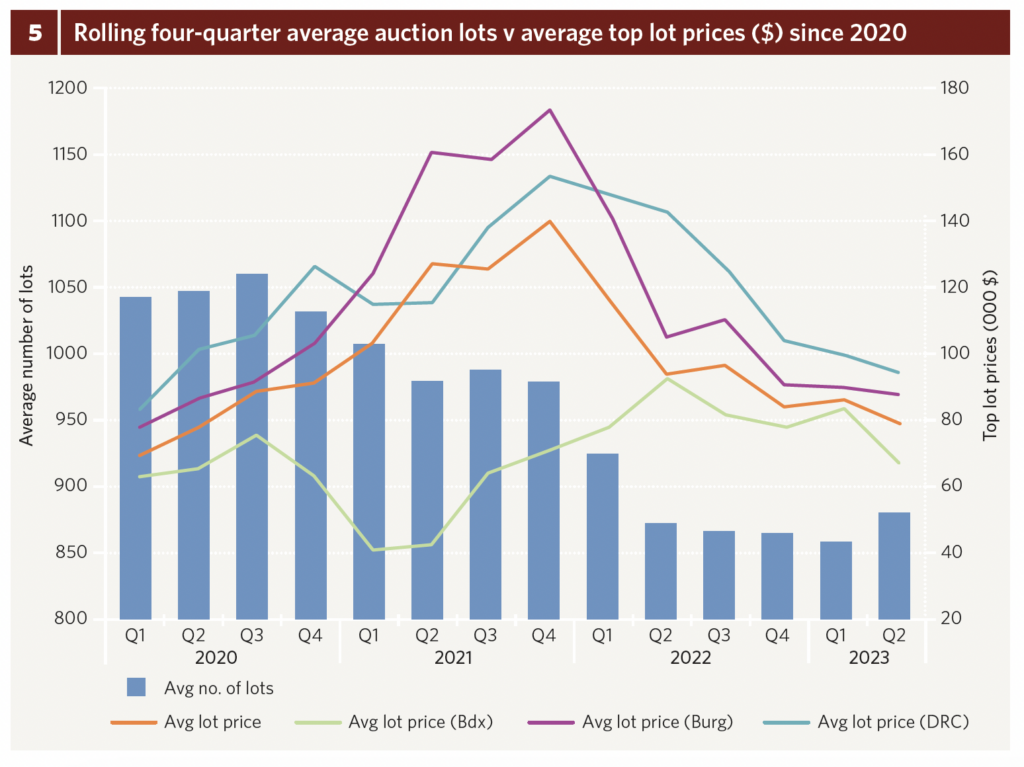

And while pockets of interest are still bound to crop up for the ultra-rare and desirable stocks, further evidence of a down-cycle can be found in lot volumes and top lot prices. Analysis of four-quarter rolling averages since 2020 suggests that both buyers and the access to high caliber lots attracting strong demand have decreased since the auction market peaked toward the end of 2021 (fig. 5). Thereafter, the average top-lot hammer price of live auctions has fallen steeply, by 43 percent between Q4 2021 and Q3 2023. Regionally, Bordeaux top lots were slower to peak than Burgundy, reaching a high in Q2 of last year before then declining 38 percent to end June 2023. Burgundy top-lot prices have been in freefall since the end of 2021, dropping a frightening 49 percent. And while Burgundy top lots show signs of stabilizing overall—with prices virtually flat for the past two quarters—the region’s dominating auction star, Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, may still have further to fall.

A market galvanized

On paper, this paints an ugly picture for the immediate future of the fine-wine trade. Merchant activity is low, and even with some access to unicorn wines at competitive prices, collectors may simply have had their fill for the time being. In reality, current market conditions provide the perfect hunting ground for new entrants, or indeed anyone with deep enough pockets and a good dose of patience willing to take discounted deals and sit on their wares for some years. Looking at the full fall schedule of auctions, and with a new Burgundy vintage due for release toward the end of the year, there will be opportunity aplenty for those willing to jump back in the game. Wilmoth comments that, ultimately, “the rich are only getting richer,” and this can only be good news for fine wine, since competition continues to increase for the most sought-after wines.

Still, if the outlook appears bleak for 2023, my prediction is that the scales will tip back again in 2024, albeit less vigorously than the frenzied purchasing period during the global pandemic. While some merchants and Bordeaux négociants might kick me for writing so, a global market cleanse could be just what fine wine needs.

Stockholders with solid capital backing could help consolidate the market, prices will “correct,” and consumer demand could rebalance geographically, reducing the historical bias of markets such as the UK or Hong Kong. For now, all signs point toward a new era for fine wine: galvanization.