There was-as the fine-wine trading platform Liv-ex likes to remind us frequently- something fabulously clearheaded and unsentimental about the original formulation of the 1855 Bordeaux Classification. When the list was prepared for the Paris Universal Exhibition, there was no mucking about with terroir assessments, tasting panels, or other subjective judgments.

Wineries were arranged into the different categories according to one brutal criterion: What are you worth? It was all about the price the wine could fetch on the Bordeaux Place. As the years progressed, of course, these terribly crass origins tended to be forgotten, and as each château’s position in the Classification became entrenched, so they all began to take on the illusion of God-given permanence.

If the 1855 Classification resembles anything today, perhaps, it’s not the perpetually volatile Dow Jones Index or FTSE 100 so much as the ossifying pre-Revolutionary French aristocracy.

As a company that has, since its inception, attempted to bring the finewine trade the tools, transparency, and a little of the culture of the trading floor-not least in its own fine-wine equivalent of the FTSE 100, the Liv-ex 100-it was no surprise when Liv-ex decided to remind us of how far the 1855 Classification had strayed from its original purpose. This the company did in 2009, with the publication of its first reclassification of the top Bordeaux estates-a list that, as Liv-ex managing director James Miles said at the time, “aim[ed] from the outset to re-create the conditions of the 1855 Classification. To base it wholly on price-as the 1855 Classification was-and include only the major estates of the Left Bank.

In essence, to create the classification that would have been drawn up if today’s prices were those prevalent 154 years ago.”

The 2011 Bordeaux Classification

The exercise was, in no small part, a publicity stunt for Liv-ex to advertise the price data it accumulates from its fine-wine trading platform. But it was no less interesting for all that, and it was widely reported in the wine media and blogosphere at the time. Now the company has repeated the exercise using the same methods, and once again, especially for keen Bordeaux watchers and iconoclasts, it makes for fascinating, if not quite earth-shattering, reading.

In both the 20o9 and the 2011 classifications, the methodology was the same. A château must have a minimum production of 2,000 cases to qualify (in order, Liv-ex says, “to remove the distorting effects of super-cuvées”).

Only wines from the Left Bank (Médoc and Pessac-Léognan) were considered, and only their first wines. Liv-ex then worked out the average case price for the past five vintages (2005 to 2009 in the case of the new list) for every qualifying wine (based on the lowest available wholesale price ex-duty and sales tax) over the five years leading up to, in the case of the latest list, April 30, 2011. As with the 1855 Classification, Liv-ex then calculated five price bands into which each of the qualifying châteaux might fit. For the 2011 classification, the bands were based on those worked out for the 2009 classification, which were “modified by calculating the average price difference between the two studies for the wines in each class and applying this to the original price bands.”

Even this calculation tells you something about price inflation at the top of the Bordeaux hierarchy, with the first-growth price band some 60 percent up on two years ago, while the fifth growths are up just 11 percent:

First growths £3,300 and above, per 12 x 75cl case (£2,000 in 2009);

Second growths £700-3,299 (£500- 2,000 in 2009);

Third growths £400-699 (£300-500 in 2009);

Fourth growths £280-399 (£250-300 in 2009);

Fifth growths £220-279 (£200-250 in 2009).

Winners and losers

So, what of the nitty-gritty? Which châteaux have risen, and which have fallen? The biggest winner in this year’s chart is arguably Château Duhart- Milon, which has been elevated far above its original 1855 fourth-growth status and 38th-placed ranking to second growth and 11th position today-up from second-growth status and 3oth position in 2009-and with an average case price of ??????1,147 over the past five years. Not far behind is Château Beychevelle, which was a fourth growth ranked 42nd in 1855, a third growth ranked 25th in 2009, and is now a second growth ranked 18th.

Pontet-Canet has also made secondgrowth status but with a considerably less dramatic leap than it managed in the previous classification: Ranked 18th and a third growth in 2009, having been a lowly 45th and a fifth growth in 1855, it is now number 16 in the overall ranking. Other high achievers compared to 2009 include Château Batailley (still a fifth growth but up 15 places in rank to 44); and châteaux Rauzan-Gassies and Dauzac (both still fifth growths, both up nine places to 47th and 48th place respectively).

At the top of the pile, meanwhile, it will come as no surprise to learn that the Asian fascination with Château Lafite has helped it regain the numberone spot with an average case price of £11,043-almost £3,000 higher than the estate it replaced at the top, Château Latour. Château La Mission Haut-Brion holds on to its position as an unofficial sixth first growth, but only just; it is almost in a kind of super-second class of its own, equidistant from Château Haut-Brion above and Château Palmer below.

Interestingly, Liv-ex says that Les Carruades de Lafite would qualify as a first growth (above La Mission) had it been permitted into the classification, while 12 other second wines would also make it into the classification, with the second wines of all the other 1855 first growths now qualifying as second growths.

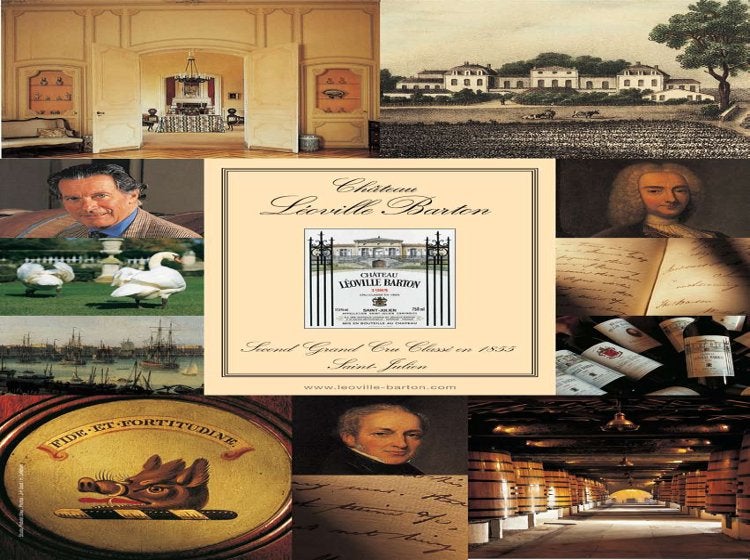

Among the higher-profile estates on the snaking path down the classification, meanwhile, is Château Léoville Barton, which slips six places, trading its second-growth status for a place among the third growths in the process. Other losers include châteaux Malescot St-Exupèry and Giscours (both down six points, with Giscours losing its third-growth status in the process) and two châteaux that were introduced in the 2009 classification, Sociando-Mallet and Haut-Marbuzet, both of which have seen their rankings fall by eight places.