The wines are undoubtedly excellent. But, in a context of global financial unrest, will prices prove sufficiently attractive for buyers to invest now rather than a few years down the line? Chloe Ashton reports on the Bordeaux 2022 en primeur campaign.

Smiles on the faces of Bordeaux producers during this year’s en primeur week spoke volumes. “I’m not one to blow my own trumpet, but I think this is the best wine we’ve ever made,” confesses Bruno Lemoine, managing director of Château Larrivet Haut-Brion. Similar echoes from properties on both banks invoking comparisons to 2009 and 2010 say just as much—the bordelais are unequivocally proud of the vintage they have produced in 2022. And they have good reason to be; the best wines are astonishingly fresh, with only the ripeness and chin-dripping juiciness of their fruit profile to give away the all-time high in sunshine hours that characterize half the story of this vintage. Any signs of the other half—potential for high alcohol and overpowering tannins linked to the heat, and record drought throughout the growing season—are largely well-masked and integrated when it comes to the top wines.

Oh, that were quality enough. Delightful as it was to experience such widespread positivity flitting between châteaux during en primeur tastings, most participants grinning from ear to ear, you could spot the buyers from a mile off. Every mention of “a legendary vintage” or “our best wine yet” drew another worry line on the faces of négociants, as their release radars translated the messages into price tags. Blown away as I was by the wines, the scepticism troubled me: Why, I asked myself, could we not just recognize the exceptional quality of the wines, and market them accordingly? If major critics’ scores are to be trusted, top Bordeaux is still consistently better value for money than any other wine region in the world. Enter the en primeur system, which for all its brand-building power, puts a magnifying glass over pricing as the only differentiator between the hundreds of wines released within six to eight weeks of each other.

Be not afraid of greatness

Let us first take a moment to revel in the happiness of the vintage. While I leave it to critics to discuss the detail of the growing season, it is important to take stock of how Bordeaux has produced exceptional quality under such extreme conditions in 2022. To call it a miraculous vintage is a disservice to the viticultural and winemaking innovation that has been in play for decades. At the annual primeurs press evening hosted by Domaine de Chevalier, owner Olivier Bernard joked that “the best wine I’ve ever made is the one I’ll produce tomorrow”—an appropriate homage to Bordeaux’s ambition and capacity to futureproof its wines. Indeed, the crus classés have both the financial means and the foresight to have observed, analyzed, and pre-empted rising temperatures for some time, readying themselves for a vintage like 2022 since at least 2003, if not well before.

At Château Figeac, commercial manager, Alexa Boulton, reminds me that the late owner of the now Classé “A” property, Thierry Manoncourt, chose deep-plunging rootstocks in anticipation of water deficit decades ago. Otherwise, Figeac’s blue-clay soil did much of the work to produce 2022, retaining the moisture for which its vines were able to delve deep. Fabien Teitgen, winemaker at Smith Haut-Lafitte speaks of learning from the Cathiards’ vineyards in Napa for this vintage—no deleafing and vines left in a “Y” shape provided the best possible shade to the Pessac property’s grapes, while avoiding any soil-tilling prevented water evaporation throughout the ripening season. Every viticultural decision preceding this remarkable vintage counted toward its success—and with the experience of 2016, 2018, and 2020 fresh in producers’ minds, top estates managed what nature gave them, perhaps more deftly than ever. If luck had any hand, it was simply that “2022 came after 2021, which recorded the coldest winter in ten years,” explained Omri Ram, winemaker of the Lafleur stable. “The vines finally got a real rest, and then trained like athletes from early on in the 2022 growing season to withstand the heat and drought.”

While no-one can deny the clear display of vinous capitalism here – the top terroirs in the hands of the best châteaux, affording the biggest budgets to fuel the fastest technical improvements in the vineyard and cellar – it does not take away from the sheer expense of these advances. Big money has been spent in Bordeaux over the past couple of decades, and only because of this are winemakers able to create the kind of wines we have the fortune to taste and buy today. By this logic, increased prices in 2022 make complete sense – the wine costs more to make and economies of scale don’t exist, since production levels of the top wines are decreasing. But this is only the internal context, which has the misfortune of converging with external factors placing a dark shadow over the 2022 campaign.

What’s past is prologue

Any naïve hopes of a peaceful and seamless release program that I carried out of tastings quickly wore off once my feet were back on firm ground, treading carefully around our current economic context. Inflation is at a 40-year high, banks are literally failing, and all the while, wine lovers have already filled their cellars with so many brilliant Bordeaux vintages of the recent past—2016, 2018, 2019, 2020. Back I fell into primeurs skepticism, digging desperately for compelling reasons to buy 2022. There will be reason aplenty to buy it—in three years once bottled, in five to ten years when some of it enters its drinking window, in 20 when it is at its prime, if much harder to find—but what argument is compelling enough to convince me now? My heart sinks to answer, but the only imperative is price.

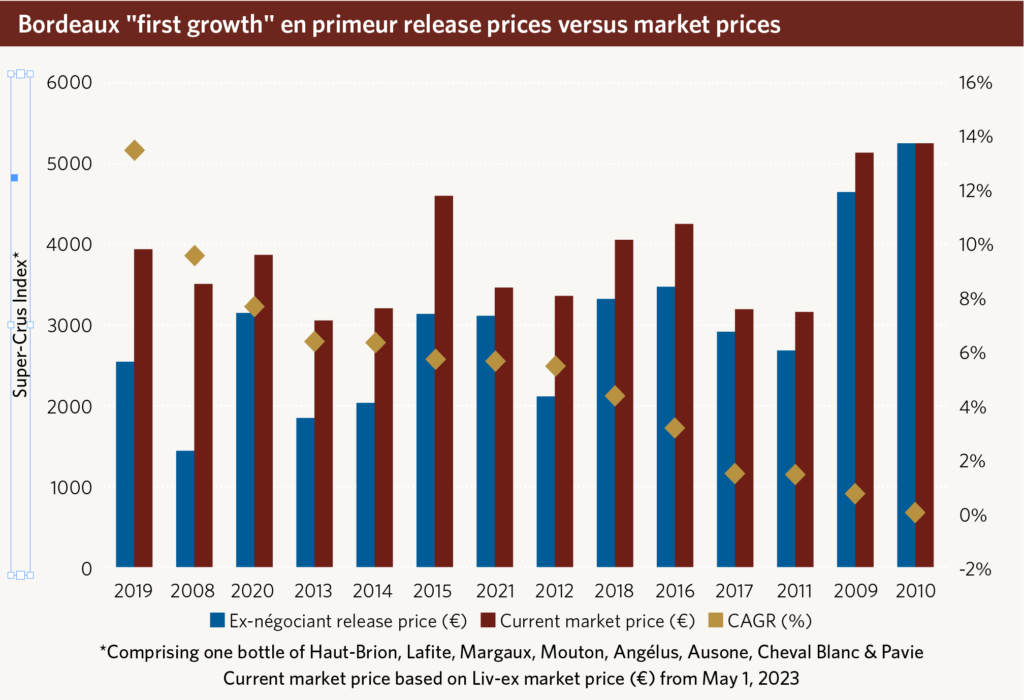

A reminder of the golden en primeur rule: Purchasing en primeur affords the consumer a competitive price on wines that will otherwise be more expensive (and perhaps secondarily, difficult to source) once in bottle. This edict has been disregarded to varying degrees by en primeur releases of the past 15 years, damaging the system’s reputation. Looking more closely at this period of campaign history, it is clear that the pricing of Bordeaux has never fully recovered from the 2010 vintage. I tried to shy away from this comparison throughout tasting-week conversations with négociants and merchants, but the closer the campaign drew, the more obvious the similarities between scenarios became.

Reluctantly, I crunched the numbers, assessing release prices relative to current market prices (as of May 1, 2023) of eight high-profile wines: the four Médoc first growths that still release en primeur, and four Right Bank icons. Looking at this “Super-Cru Index” collectively, the results—ordered by CAGR (compound annual growth rate)—demonstrate clearly the en primeur campaigns that “worked”—and none better than the 2019 vintage. Amid the global pandemic, and fueled by the complete nescience of how an en primeur campaign was to be conducted in such alien conditions, Bordeaux producers dropped their release prices for 2019—a reportedly excellent vintage. Just under three years later, prices of the top eight wines from the vintage have grown by 13 percent per annum. In stark contrast, the highly anticipated 2010 vintage was brought to market at such steep prices that these have only just recovered their lost ground. However impressive the quality of 2022, the fine-wine world can ill afford a repeat of 2010.

Rumors of 2022 release prices 20–25 percent higher than 2021 quickly spread during the official tasting week. Edouard Moueix, managing director of négociant JP Moueix and owner of Château Bélair-Monange, tells me, “I’ve heard all sorts—releases at the same level as last year, 10 percent up, 20 percent up—it’s a mixed bag,” he confesses, “but I hope prices will be set by properties on a case-by-case basis.” He diplomatically avoids expanding on the anxiety of most négociants today—namely, that a strategy of “follow thy neighbor,” fixing en primeur pricing on the release of the vineyard next door, simply won’t fly. In another year of extreme economic uncertainty, what the market really needs is another campaign like 2019. “Some châteaux felt as though they lost out, or released too low in 2019,” Moueix tells me. And perhaps it is unrealistic to expect properties to match 2019 starting prices, given the relative increased cost of production associated with the shift between vintages into a totally different financial era. Envy the job of Bordeaux estates’ commercial teams I do not, because striking the right balance between representing the quality of the vintage justly, and being sympathetic to its release environment, is well-nigh impossible.

I wasted time, now doth time waste me

Beyond quality and price, the only other two dials to play with when trying to engineer campaign success, are volume and time. Release volume decreases from properties withholding more stock will at least alleviate some pressure on négociants running credit to finance campaigns over the short term. The fact that borrowing money is no longer free will force buyers to make more scrutinous choices, and potentially turn down allocations based on price. Equally, the slight lull in demand for wines in major markets—the US, UK, and China—experienced in the first quarter of 2023 will compel merchants and importers to think twice before investing heavily in 2022. The trade will likely have needed to put serious weight behind marketing their personal convictions in this campaign, as consumers approach the vintage with a mindset for seeking value. This offers a glimmer of hope to estates pricing in the middle ground—the usual en primeur danger zone—whose quality this year means they may find homes among habitual first- or second-growth buyers choosing to downgrade.

Time, dare I say it, will surely also have its role to play this year. At the time of writing, Cheval Blanc had already set a positive tone for the campaign, releasing at £480 per bottle—22 percent above the 2021 vintage, but crucially well below back vintages of comparable quality (2019, 2018, and 2016) on the market. Releasing minutes later, Angélus took the trade by surprise with an opening price of £358—the highest-ever en primeur release from the property, placing the 2022 above virtually all back vintages on the market except the 2012. This stratospheric divide in strategies may cause some properties to waver. On the one hand, those following Cheval Blanc’s example may offer the campaign some much-needed momentum. On the other hand, properties taking lessons from Angélus, or even taking the time to contemplate doing so, could grind the campaign to a halt—or worse, see it trudge along at hefty prices that risk deflation if financial markets crash later this year.

Beyond the specific and short-term decision on release time, there is an additional temporal dimension that is perhaps more troubling over the long term. The brutal question consumers should ask themselves remains: “Why should I buy 2022 right now”? Educated buyers know all too well that the campaign can create false pressures to secure certain wines immediately, rather than between six and 18 months down the line. In my mind, there is no doubt that 2022 is a must-have vintage, but only release pricing will serve to convince customers that it is a “must-have-right-now.” A pessimist might therefore expect a quiet campaign. Stephen Browett, chairman of leading UK merchant, Farr Vintners, states his en primeur 2022 expectations clearly: “If the wines are priced the same or higher than the current prices of the 2016, 2019, and 2020 vintages, that will kill it.” Would that really be a problem? For the châteaux, in the short term, no; nor for négociants with healthy capital to hold stock, but it has the potential to ruin smaller players, and thus adds another knock to general confidence in the en primeur system.

Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t

Imagine for a minute the power of the Bordeaux marketing machine—the official tasting week, visits, releases—based on deliverable wines. Is it madness even to suggest it? Is it even economically viable, after decades of the same early cash influx, now imbedded in shiny new, state-of-the-art winemaking facilities across Bordeaux? Madness indeed: I forget not only myself, but also the power of “fomo,” the fear of missing out. And despite the trade’s penchant for berating this historic distribution system, its collective and overwhelming love for Bordeaux will out in the end.

Combine this love and fear at the right frequency, and we could find Bordeaux’s superpower restored by “the legendary” 2022. However high the prices, it may take only the enthusiasm of one or two leading participants jumping in with both feet, to start a stampede of additional players racing in. And herein lies the beauty of the whole en primeur performance: Whatever logic we may attempt to apply, buying wine—whether it is yet available or not—is so often an emotional choice in so many ways. Despite the economic storm clouds looming, those with the means might simply choose to ignore the numbers, keep calm, and carry on buying en primeur.