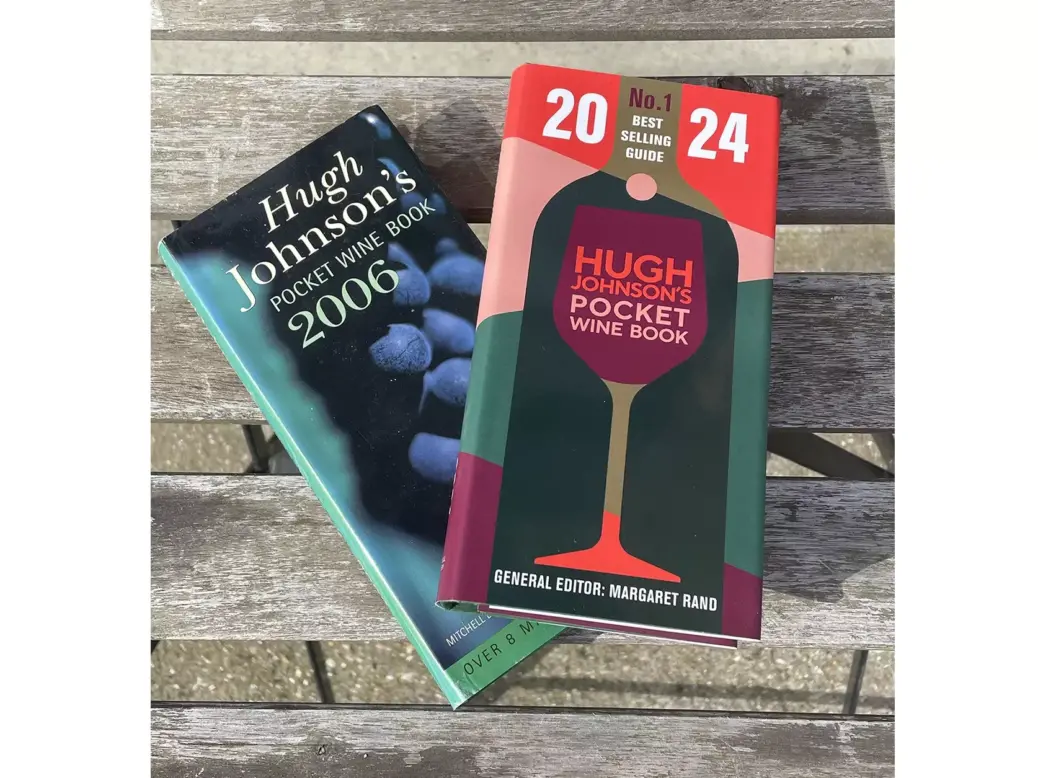

In one sense, 2006 seems like yesterday: That was my first edition of Hugh Johnson’s Pocket Wine Book. I also wrote a piece that year on the wine cellar at Buckingham Palace for WFW: the Palace didn’t want mentioned the not-very-exciting information that the Queen drank gin and Dubonnet at dinner, and Prince Philip drank beer.

Another reign, both at the Palace and at the Pocket Wine Book—not that I am in any way comparing, etc etc. And Hugh, I should add, is going strong. We had lunch one day a couple of years ago, as we do from time to time, and he mooted the idea of his doing less on the book and my doing more. The publishers then said, well actually, he wants you to take over.

It was an act of great generosity. Hugh Johnson’s Pocket Wine Book was his baby, born in 1977, and when I started working on it in 2004, for the 2006 edition, it knew exactly what it was doing. But when you look at the 2006 edition now … Spain and Portugal shared a chapter. They still share a map, much to the annual annoyance of André Ribeirinho, my Portuguese contributor, but it saves half a page for more Portuguese entries; and space is at an even greater premium now than then. Then there were eight pages of ads for other Mitchell Beazley wine books in the back—eight pages! That didn’t last.

Wine and the Pocket Wine Book

More entries, and more entries again. That’s the story of the Pocket Wine Book, and it’s the story of the wine world. More growers. More styles. More great wines. More and more to squeeze in, every year.

But things don’t happen overnight in wine. What is the most important development in wine since 2006? Natural wines, I would say, and their gradual blending into the mainstream: you don’t even need a beard to drink them now. But in 2006 we noted approvingly that Mooroduc Estate (Mornington Peninsula) used wild yeasts. The world was between two styles then. Of Château Valandraud we said: “Silly prices for the sort of thick, vanilla-scented wine California can make.”

One reason why Hugh and I worked together happily for so many years on the Pocket Wine Book is that we shared the same view on wines that were over-extracted to the point of anonymity (bad) and on wines that are elegant, fresh, and moreish (good). And fashion has, since 2006, swung our way, spurred by all the things that make natural wines natural: spontaneous ferments often mean less obvious fruit flavours. Excessive oak was abandoned remarkably quickly. Massive extraction was replaced by infusion. Where everything used to taste like Cabernet Sauvignon or Shiraz (it became difficult to tell which), now everything tastes like Pinot Noir.

And sometimes more like Pinot Noir than Pinot Noir does: It’s not unknown, in a hot vintage, for Côte d’Or reds to inspire the same adjectives you might use for, say, Grenache from further south. Climate change is a big development for wine, but it certainly hasn’t happened just since 2006. I remember back in the 1990s growers saying that 1988 was when they first noticed a difference of climate. Then there was 1995, then 2003, and 2006, and 2009, and then one hot year after another. Acidity and elegance have become fashionable just as it has become more of a search to find them. Ironic, that.

Sustainability and biodynamism? Yes, that’s the other big evolution, and that, too, started long before 2006. Winemakers are in love with their land; that’s the thing. However little difference it might seem to make to a planet where the big players seem determined to destroy the seas and the atmosphere and the land in between, not to mention the people, winegrowers want to encourage butterflies and ladybirds and microfungi on their particular patch of the earth’s surface. Look at the global news on any day of the week and their efforts might seem futile; a form of escapism into a la-la land where some people can count returning bird species while others try to duck missiles. But it’s not either-or; it’s more akin to the sage advice that if you want to change the world, start by changing yourself. Wine is a force for good in the world. Valandraud and its ilk have changed; but that has not changed.