From the abstemious King Richard II to the “tastelessly lavish” arrangements of King George IV, Stuart Walton prepares for the coronation of King Charles III by looking back at the wines used to mark the coronation of monarchs through the ages.

The coronation of a new monarch has customarily been the occasion for much thoughtful reflection on the tradition and heritage the event represents. It has also been the occasion for much drinking, whether of dexterously decanted old claret taken in tiny sips from glasses the size of eggcups, or of the raucously drained goblet thrown back amid shouts of jollity.

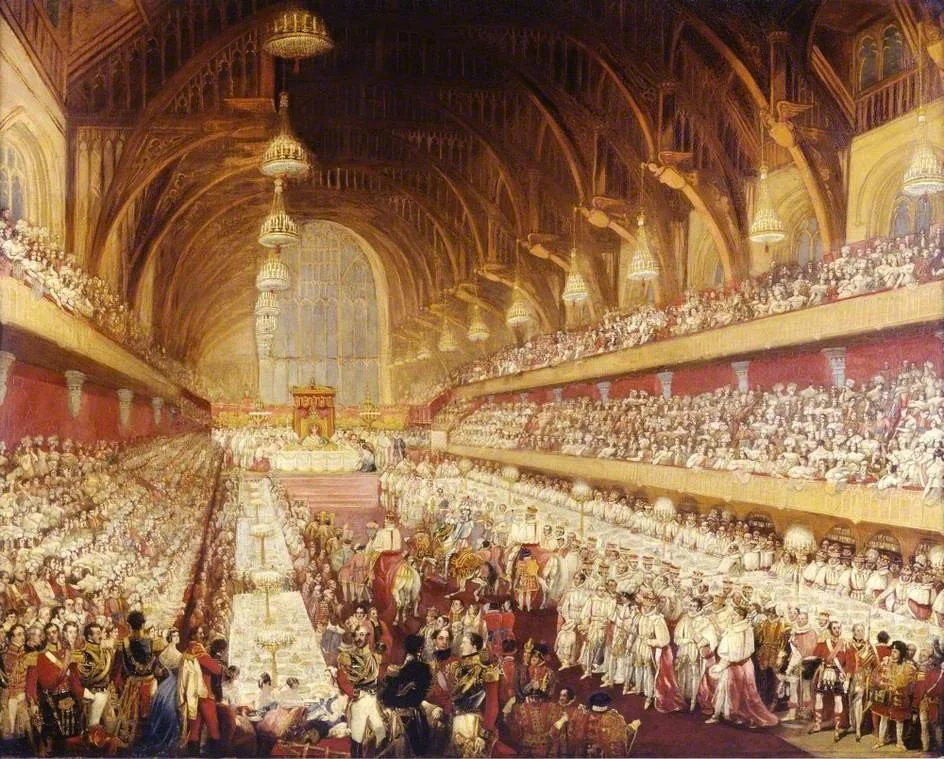

In Great Britain, coronations were for centuries marked with a large ostentatious banquet in Westminster Hall, a practice initiated at the crowning of Richard I in 1189 and maintained up to the satyricon feast staged for George IV in 1821, at a cost in today’s monetary values of around £20 million. George’s banquet was considered so tastelessly lavish, and as punctuated by comical accidents as a Drury Lane farce, that his successor, William IV, did away with the official banquet once and for all.

Wines were the principal liquid refreshment at all occasions. We are not at all surprised to learn that Edward VII was toasted at his private coronation dinner in the summer of 1902 (it was postponed by a month as he wasn’t well on the original date) in Mumm Cordon Rouge. The order in which wines were matched to dishes in modern coronation menus might seem bemusing now. At Elizabeth II’s dinner in 1953, the 1934 Lafite that was paired with rack of lamb was followed by a vintage Pol Roger from the same year, to accompany asparagus in sauce mousseline.

A fascinating glimpse into the way such celebrations reflected the times is afforded by a wine list offered during the coronation of George VI in 1937. As economic depression continued to grind down a continent hurtling to another ruinous war, the bill of fare included, among the routine opulence of classed-growth Bordeaux and grand cru Burgundy, such temptations as Light Golden Sherry, Coningham’s Three Star Ruby Port, and the finest vintage Liebfraumilch. Autres temps, autres moeurs.

Even these discernments look refined in light of the stress on quantity over quality that characterised the feasting of earlier centuries. Guests at the coronation of Edward II in 1308 put away 1000 casks of wine among them. Who cared where it came from? At the crowning of Richard II in 1377, the king appears to have been served only the finest water, but he was only ten years old. He was eventually crowbarred off the throne by Henry IV, whose own banquet in 1399 was lubricated by wine that had been sweetened with honey, thickened with rice-flour, and coloured with the juice of mulberries or the ground bark of the red sandalwood tree, a cocktail recipe surely overdue a revival.

A public spectacle

The coronation banquet became a public spectacle, with semi-privileged onlookers installed in ranks of balconied seating looking down on the 300 or so diners fortunate enough to be invited to the main table. Three thousand people crammed Westminster to watch the gorging at the banquet for Richard III in 1483, the tradition that still informed George IV’s ceremonial. When the main guests withdrew, the upper galleries emptied as the spectators swooped to vacuum up whatever was left. Receipts for the wine orders indicate the presence, among an ocean of the usual French suspects, of 100 gallons of an iced wine punch. One can only hope it hadn’t warmed up by the time the hoi polloi got to it.

At Queen Victoria’s coronation ceremony, a creaking five-hour affair at which all manner of things went wrong, the royal couple were permitted to nip out at intervals when they were not needed. A buffet was provided in St Edward’s Chapel, where platters of sandwiches and bottles of wine had been spread out on the usefully positioned altar.

In France, coronations traditionally took place in the Cathedral at Reims, at the epicentre of the Champagne region. The banquet following the crowning of Hugh Capet in 987 was graced with a plentiful affordance of the local wine, a thin, still, barely alcoholic, pale pink potion, at least made from actual Pinot Noir. His distant successors would be plied with the sparkling article, which Philippe II, duc d’Orléans, did much to popularise at the French court during the regency that followed the death of Louis XIV.

It is a dignified aspect of British monarchical succession that the crowning of a new head of state should be marked by the drinking of wine among the populace as well. If you can’t celebrate that, then when? Thus does Samuel Pepys venture forth during the festivities for the coronation of Charles II in 1661. It’s been a long day:

“At last I sent my wife and her bedfellow to bed, and Mr. Hunt and I went in with Mr. Thornbury (who did give the company all their wine, he being yeoman of the wine-cellar to the King) to his house; and there, with his wife and two of his sisters, and some gallant sparks that were there, we drank the King’s health, and nothing else, till one of the gentlemen fell down stark drunk, and there lay spewing; and I went to my Lord’s pretty well. But no sooner a-bed with Mr. Shepley but my head began to hum, and I to vomit, and if ever I was foxed it was now, which I cannot say yet, because I fell asleep and slept till morning. Only when I waked I found myself wet with my spewing.”

And so say all of us.