Stuart Walton on the long history of drinking vessels, from gourds to the changing fashions of modern wine glasses.

In the beginning was the gourd. The first bespoke drinking vessels were the hollowed-out skins of large vegetables like the calabash, tough enough to withstand transport, an advance on slurping river water from shells. In Chinese antiquity, a technique would be developed for training gourds in molds so that they grew into commodious shapes, but the much more workaday glazed earthenware, originally fired in pits and sealed on the inside so as not to absorb liquids, had begun to be perfected around 30,000 years ago.

An Egyptian innovation

Glass, without which the sensuous appreciation of wine would be unthinkable, was an Egyptian innovation of the last quarter of the third millennium BC. Skilled craftsmen under Pharaoh Thutmose III (r 1479-1425 BC) refined the technique of core-forming glass vessels, by spinning the molten glass over a solid, removable core. The oldest archaeological finds are of this type. It would not be until the first century BC that the glass blowpipe would be invented, also in Egypt, but glass had long since been a covetable elite commodity, so much so that when the Romans arrived, they adopted the glass vessel themselves as a sign of exquisite cultivation. By the 13th century, the Republic of Venice had become the recognized center of European glass-making, to the extent that the foundries were eventually sequestered on the island of Murano, for fear that the virtual industrialization of glass-making on the mainland constituted a fire hazard that threatened the city’s very existence.

The semiotics of refinement often turn on the notion of fragility, the same impulse that would eventually make bone china and other types of porcelain collectable. Glass, even more than whiteware, connotes delicacy, not least for its sparkling transparency, its deference to the appearance of whatever goes into it. Typically colored and highly decorated in earlier eras, the drinking glass gradually shed all its outward adornment until it was reduced to the purity of what was known as “ice” glass. The wine at Leonardo’s rendering of the Last Supper in the 1490s has been served in a matching set of anachronistic plain glass tumblers. In the previous decade, Domenico Ghirlandaio’s frescoes of the same scene at various locations in Florence, show not only similar glasses, but also the elegant, long-necked, crystal decanters from which the wine has been poured.

In their cups

Refinement and delicacy have never been the whole, or even the principal, tenor of winemaking cultures. The festive aspect of drunkenness produced a style of drinking vessel that entered into dialogic relations with the drinker. The red-figure and black-figure drinking cups of classical Athens, central to the male-bonding wine ritual of the symposium, often depicted scenes of unbridled concupiscence, either as reminder of the compromising temptations to which wine led the drinker, or as positive encouragement to them. Fashioned with a broad, shallow bowl, the kylix was perfectly formed for imbibing while recumbently lolling on sofas, its interior base often painted with a carnal scene that could only be enjoyed when the cup was drained of its opaque red wine. The relief figuration on the Warren Cup in the British Museum, a Greco-Roman silver drinking vessel probably made during the lifetime of Christ, shows two depictions of sex between older and younger men, one of which is being enjoyed by a peeping figure behind a door, with whom the drinker is invited to identify.

Elsewhere, the injunction to drink comes from the more obvious recourse of vessels that refused to be set down until they were empty, such as the Scythian drinking horn that soon left its bovine origin behind and became a thing of precious metal. The medieval round-bottomed glass insisted on the obligation to hospitality and comradeship in drink, since you could only cling on to it for dear life until you had drained it to the dregs.

Today’s wine glasses

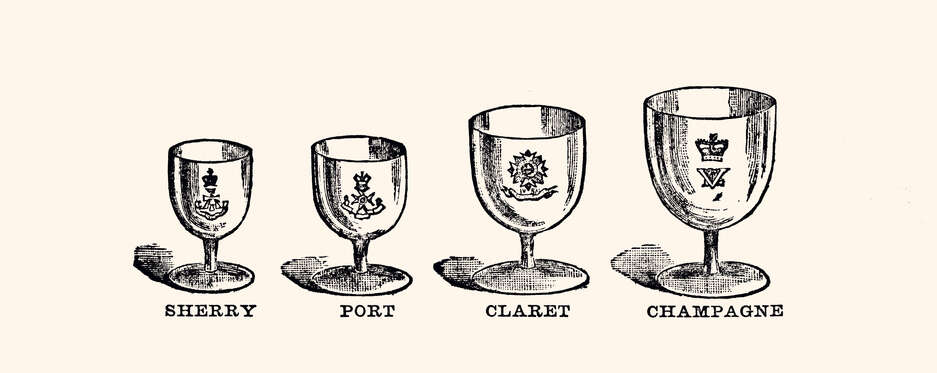

What has happened to glass in the present day continues to reflect habits in social drinking. Just as wine glasses were succumbing to a gigantism that officially developed from the spread of connoisseurial appreciation, but also handily catered to modern greed, the first stirrings of a countervailing shrinkflation are upon us, in a return to the elegant small thimbles from which our Victorian forebears sipped their wine.

Shapes and sizes matter. We now know that fine spirits are better taken from something small and narrow, the better to enjoy the aromatic tones that are surrendered to the hot alcohol prickle of a broader surface area. Donate your brandy balloons to the charity shop! Even wine, though, becomes something else again when drunk from some unfamiliar material. An online correspondent in Chelyabinsk once sent me, from the goodness of an uncorrupted heart, a pair of onyx wine goblets. About once a year, I pour something full of youthful fruit, in rude red health, into their cold grey-brown embrace, and the wine reverts to its primal role as an earthy, hearty intoxicant that isn’t asking to be swirled or swooshed. Or even looked at.