From the inventive witches’ brews of 18th-century fortified wine shippers, to the elaborate homespun fakes of Rudy Kurniawan, Stuart Walton investigates the ways in which the unscrupulous have brought adulteration and fraud to wine.

For such an essentially simple product, wine is capable of concealing a multitude of sins. We assume that the bottle will contain very little other than fermented grape juice, perhaps assisted in its vinification with a little chaptalizing sugar, or an injection of liqueur de tirage to make it re-ferment into fizz. A judicious dose of sulfur dioxide inhibits spoilage. Cultured yeasts and malolactic bacteria are only in the interests of giving a natural process a shove, while the more exotic likes of chunks of Aleppo pine resin will be filtered out at the bottling. What you are drinking, though, is grape juice, from where it says it’s from. You hope.

Adulteration and other forms of skulduggery

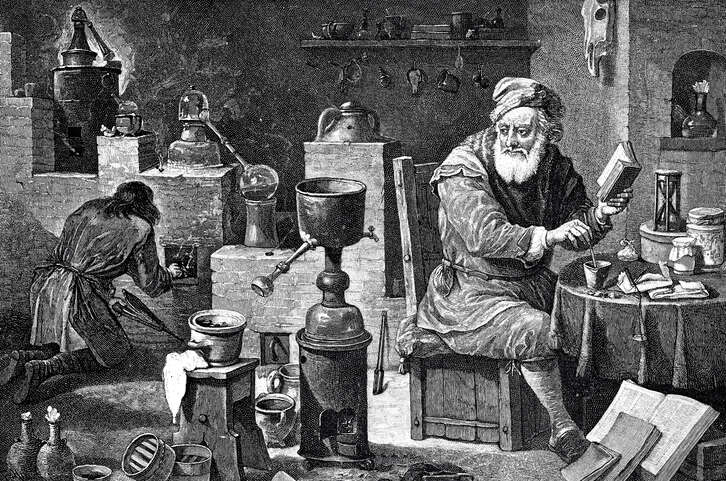

Adulteration and the various other wine frauds all turn on the assumption that the consumer will likely never suspect the skulduggery at work. In previous eras, the doctoring of wine was more elaborate than anybody would dare get away with today. When certain table wines of southern Europe began to evolve into fortified versions of themselves, the only limit was the shipper’s resourcefulness. The rapid burgeoning of English demand for Port in the early 18th century led to local estate owners adding elderberry juice, mulberries, even cider, to the wines to add a riper taste. There was a market for guidebooks that offered suggestions on to how to revive spoiled wine. One of the more reputable merchants, John Croft, noted that much Port was sweetened with raisin wine, “generally made of the very worst sort of raisins that come from Smyrna [modern-day Izmir, Turkey] compounded with British spirits, extracted from malt”—a witches’ brew, if ever there was.

Charles Ludington, in his exhaustively detailed study, The Politics of Wine in Britain (2013), cites a French visitor to England, one Pierre-Jean Grosley, claiming that he had it on good authority that the “Port wine” served in London taverns in 1765 was a squalid amalgam of wild berries, beer, turnip juice, and “litharge” (lead oxide). The Port industry took longer than most to shake off the reputation with which it had been saddled by unscrupulous vintners and shippers, but the problem of adulteration never entirely went away. There are those still living who remember what “proper” Burgundy used to taste like, when it was routinely beefed up with fiery Algerian red.

The annals of recent infamy still resound with the diethylene glycol furore that undermined the Austrian wine industry in 1985, and the altogether more calamitous methanol scandal in northern Italy the following year, which led directly to about two dozen deaths.

The crown prince of passing-off

What has been an even more widespread fraudulent practice over the centuries than outright adulteration is simple passing-off, relabeling an ordinary wine with pretensions far above its station. This has been an enormously lucrative recourse for the determined con-merchant, particularly where incautious buyers have been persuaded they are buying a venerable, historic bottle. In these cases, a scam can stand or fall on whether supposedly seasoned tasters can spot that the 30-year-old classed-growth claret they are scrutinizing is actually a ropy old Chianti.

The latter-day crown prince of such entrepreneurs is Rudy Kurniawan, the convicted Indonesia-born wine fraudster who is the subject of the Jerry Rothwell and Reuben Atlas documentary film, Sour Grapes (2016). With a combination of an extremely plausible personal manner and a none-too-sophisticated home label factory, Kurniawan succeeded for several years in fooling purses and palates in the most plutocratic circles, amassing a substantial fortune along the way. Only when Laurent Ponsot noted that his family’s estate did not produce its Grand Cru Clos St-Denis until 1982 was a penumbra of doubt cast not just on the 1940s vintages of that wine that Kurniawan was offering for auction, but on his entire Byzantine operation. At the conclusion of his trial in 2014, Kurniawan was handed a ten-year jail sentence.

The toxic and the imaginary

The news media loves hardly anything better than a tale of wine connoisseurs being fooled. It seems to beam a message of hope to those who can’t afford grand cru Burgundy. If they can’t tell it apart from something at a fraction of the cost, what are you worrying about? Context is everything, though, and the same experts who were successfully duped at a pre-sale auction tasting might perfectly well have spotted the discrepancy under blind tasting conditions. It feels as though we ought to care profoundly about what we are putting into our bodies and, at one level, we do. Nobody enjoys toxicity. But for much the same reasons that young clubbers will happily swallow a pill that purports to be a euphoric stimulant without having the faintest idea what’s in it, we go on trusting the sales patter, the promotional literature, and most of all the label, to deliver an experience that exists first of all as an imaginary ideal.