Roger Morris asks whether, rather than seeking formal classifications for natural winemaking, we shouldn’t instead borrow a more appropriate designation from the world of fine arts.

Almost 20 years ago, when natural wines had not yet captured the attention of the world’s sommeliers, I had a somewhat acrimonious conversation with one of the style’s earliest commercial proponents, American importer Jenny Lefcourt of Jenny & François Selections. I was not totally unfamiliar with natural winemaking, since, at that time, many self-taught winemakers on the East Coast of the United States made natural wines as a default position. But I was looking forward to Lefcourt’s portfolio tasting—which was being held in a crowded basement room of a New York hotel—as my formal introduction to an informal category.

A few weeks earlier, a colleague of mine had stirred up an online hornet’s nest with his newspaper column assertion that there was often a “funky” taste in some of the natural wines he had sampled and that some also seemed unstable for storage and later use. As he discovered, “funky” is not a term most natural winemakers willingly embrace.

Before talking with Lefcourt that day, I first met some of her producers and tasted their wines. I also asked them why their wines should be considered “natural” and received conflicting reasons. For example, one cited the use of absolutely no sulfur as a prime criterion, though he was okay with using cold stabilization, while a neighbor at an adjacent table said the reverse.

But if you can’t define it, I reasoned, then how can you know whose natural wine is legitimate and whose is not? Surely, I thought, Lefcourt would know. When the crowd around her cleared, that was the first question I posed.

It was not a question she wanted to hear. “I’m not interested in quibbling about words,” Lefcourt snapped, as I later recounted our conversation, the first of several times she would use “quibble” with considerable contempt. “The main issue is there are two worlds—huge companies who ferment grapes, using many additives that you’ll never see on their labels, and small, artisan winemakers whose wines tell about a place and terroir.”

Lefcourt and I subsequently have had more pleasant and productive conversations, perhaps because I didn’t re-ask that question. But the question of what defines natural wines continues to be asked, most recently because the French attempted to provide earlier this year their own answer with a new designation—Vin Méthode Nature—that permits qualified natural wines, wherever they are located within that country, to use those words on bottle labels.

Reaction to the French move has been mixed, especially in the natural-winemaking community in other countries. Wasn’t establishing official, legal regulations on natural wines a little bit like being forced to press blue jeans or encouraging the gentrifying of a bohemian neighborhood? And as some in the natural-wine community have pointed out, one problem with having an AOP, or any other legal classification, is that someone has to be tasked with policing every vineyard and every winery to verify that the producer is coloring within the lines.

Indeed, if this approach to codifying natural wines spreads to other countries, one can predict it will simply be a replaying of scenarios followed by other wine movements that have tried to separate their vineyard work and cellar practices from the norm only to establish their own norms. Procedures or movements that were once revolutionary, or perhaps counterrevolutionary, such as “organic,” “biodynamic,” “sustainable,” or “garagiste,” have succumbed to becoming standardized and forced to create their own ruling bureaucracies.

And one can also predict in time there will be a rebellion against new natural-wine rules by a few disgruntled natural winemakers who will decide to go rogue. We writers will rush to anoint their products with new formal or informal classifications, such Vin Méthode Nature Supérieure or, better yet, SuperNatural wines.

The fuzzy logic of natural winemaking

Recently, it has occurred to me that everyone, myself included, has been unsuccessfully trying to cram the round peg of natural winemaking into a square hole. We have been trying to force natural wines into a binary concept—it is natural, or it isn’t natural—when actually they fit better into the concept of fuzzy logic, which recognizes degrees of reality or truth.

As a result, perhaps a better way to think of natural wines is to abandon conventional wine classifications altogether and to anoint them with a concept from another métier, the fine arts. Natural wine cries out not to be an AOP or an AVA or to require submission to any other organizational checklist. What it really wants is the freedom of being a school—the school of natural winemaking—using the definition of school as being “a group of artists under a common influence” and thus not hemmed in by borders and regulations. Here, the common influence for winemaking would be minimal interventions in the vineyard and in the cellar.

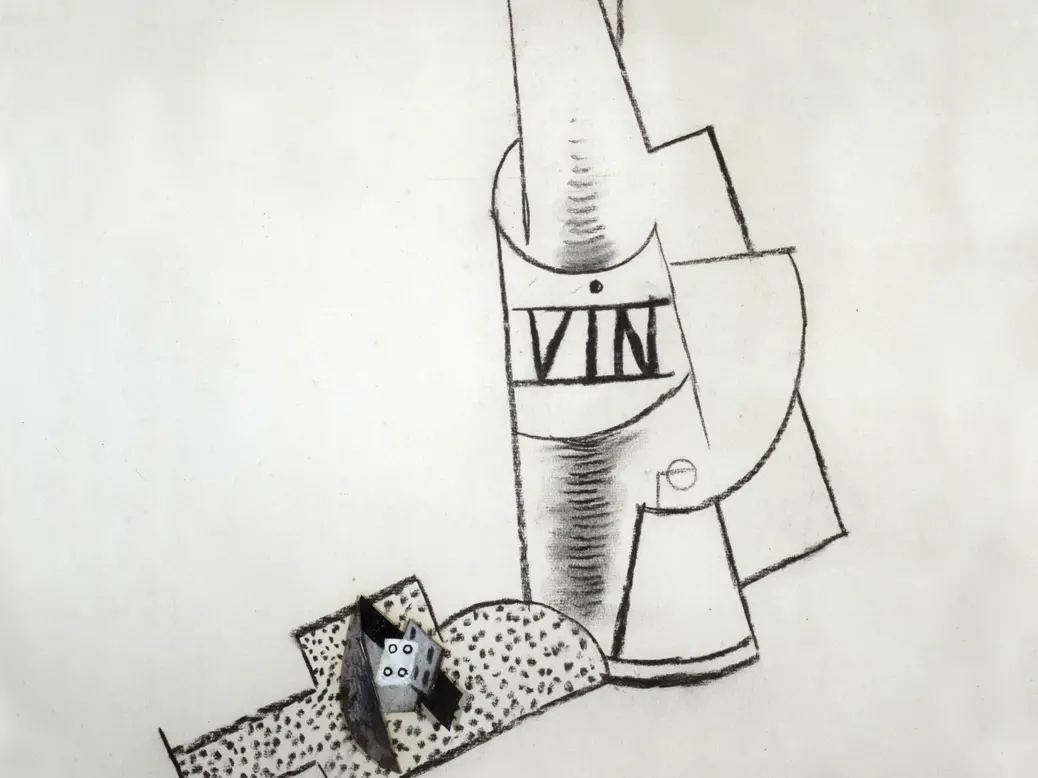

Painters and sculptors have long accepted the concept of being similar yet distinct. Picasso didn’t try to dictate a set of rules for any painter wanting to be known as a Cubist. Renoir and Degas didn’t worry over whether their varied styles fit within the confines of Impressionism. To my knowledge, Francis Bacon didn’t declare that he was a figurative and not an abstract painter. Artists do not define the school; the school defines them.

Of course, this vagueness can make for lively discussion. Imagine us as wine writers dissecting the collected vintages of a master winemaker as this reviewer did in the New York Times in assessing the work of the late artist Alice Trumbull Mason, variously labeled as a “modernist,” an “abstract artist” and a “Mondrianiste”: “The forms on her small canvases mutated with unusual variety and momentum between the biomorphic and geometric (the latter ultimately won out).” Or as does this writer in the New Yorker: “Donald Judd was the last great revolutionary of modern art. The gorgeous boxy objects—he refused to call them sculptures—[…] irreversibly altered the character of the Western aesthetic experience. They displaced traditional contemplation with newfangled contemplation. That’s the key trope of Minimalism, a term that Judd despised but one that will tag him until the end of time.”

The problem is that our discussions of winemaking normally do not incorporate that freedom and flexibility of thought because few in the wine world want to venture from the serenity of the pasture to plunge into the helter-skelter of the forest—not the regional appellations that treasure the monetary value of their reputations and want to perpetuate them without controversy; not winemakers who enjoy the stability and comfort of working as craftsmen or -women within a niche; not the wine trade or writers or educators who like categories whose rules they can easily memorize and regurgitate on command. Instead, everyone is content with being told, often by the complacent winemaker, that she “makes wines that speak of a place, that are authentic and are crafted in a sustainable manner”—a definition that seems to embrace 90 percent of winemakers regardless of their influences.

As a result, there is a tendency to consider winemakers not by their body of work over multiple vintages but rather only in terms of individual bottles (and the ratings those attain) and to worry less about their influences and the elements of winemaking that add up to their overall style—when they have one. Considering natural winemaking as a school opens up the opportunity for us to view winemakers—and hopefully for winemakers to view themselves—as more than lockstep manifestations of geography, prescribed grape varieties, and cellar regulations.

By contrast, thinking of natural winemaking as a style or as a school, rather than as a rigidly defined designation, provides a certain freedom for everyone involved, if we are bold enough to embrace it. A winemaker can have a broad philosophy of non-interventionism without feeling that every box has to be checked, particularly if she doesn’t see the logic that box represents. A wine writer doesn’t have to mentally disqualify a producer as not being “natural” if a small amount of sulfur is used before bottling. A sommelier can tell a restaurant’s guests when he presents the bottle that even if there is nothing “natural” designated on the label, “Jean Paul’s winemaking is of the natural school. Let me explain why.”

Of course, there will be disagreements—a key element that makes being part of the winemaking community so stimulating! Should a Loire winemaker call herself a garagiste even if she made 20,000 cases? “But, monsieur, I have a very big garage with many cars!” Or if a Spanish producer says his wines are biodynamic, even if he doesn’t bury a cow’s horn filled with manure? “I consider myself above all else to be a vegan.” Do producers of Bordeaux first-growth wines really worry if someone attacks them as being “industrial winemakers” because they may produce together more than 100,000 cases of grand vin per harvest?

Logistically, calling a wine “natural” without an official designation on the front label is also not a problem. Back labels have always served the purpose of letting winemakers explain how personal philosophies translate into winemaking. No one—thus far—has copyrighted the term “natural wine” or specified how it should be made. And if a major producer of thousands of cases of everyday wines wants to call them “natural,” let the trolling on social media begin.

Those of us who produce no wine—only articles and columns, books and blogs, podcasts and pronouncements—can always shame the imposters, just as art educators and art critics have long debated about who is on the inside edge of a school and who is on the outside edge. It’s a burden we can bear lightly, and those who deal in points and ratings can continue to do so unabated.

For my part, I have come to the conclusion that Lefcourt was right all along in not wanting to rigidly define natural wines—even though there might now be more satisfactory answers as to why she was.

This article was first published in WFW69 in September, 2020.