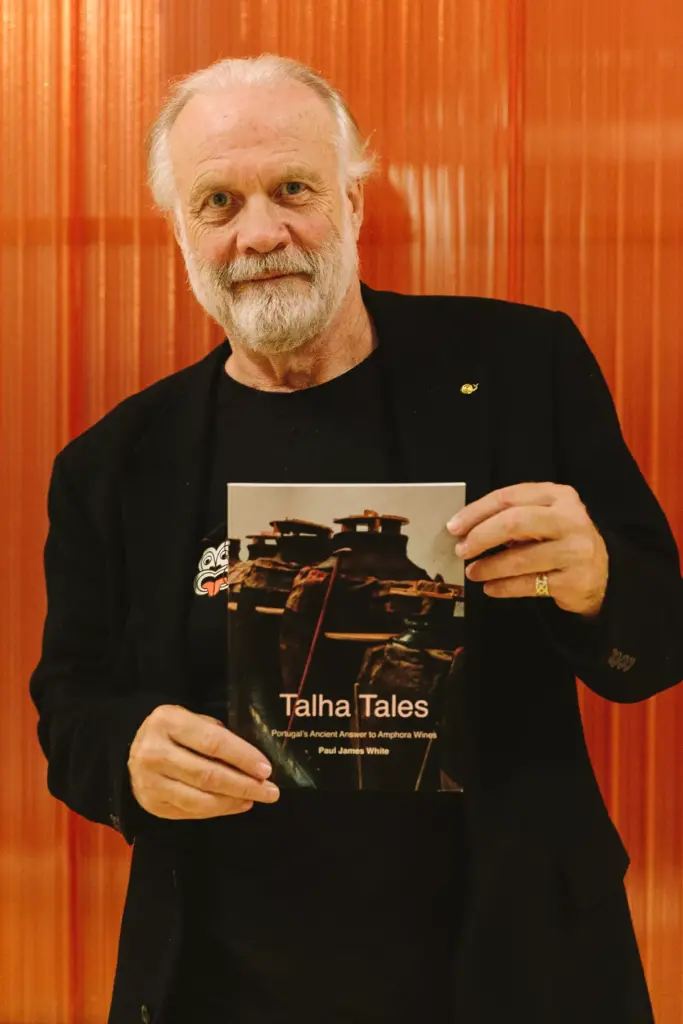

Sarah Ahmed reviews Talha Tales: Portugal’s Ancient Answer to Amphora Wines by Dr Paul James White and Jennifer Mortimer.

The Doctor (of Doctor Who) is a time traveler with an insatiable appetite for adventure, as is Dr Paul James White, albeit one bound to the earth, especially fired earth. “Bouncing around the globe, discovering new stuff about wine wherever I can find it,” White reflects, “looking back over the last couple of decades, the two most exciting things I’ve encountered are Terracotta made wines … and the great unspoiled wines of Portugal.” Published last year, Talha Tales: Portugal’s Ancient Answer to Amphora Wines celebrates both, building on the author’s seminal 2015 and follow-up 2021 articles on Alentejo’s clay-pot winemakers (WFW 49 and 74).

Reminiscent of a school textbook in format, Talha Tales is no coffee-table tome, but it is far from dry. Rather, one feels privy to White’s journey, his stream of consciousness even, as he endeavors to piece together talha’s shattered history from shards of physical evidence (from the ancient Roman ruins of São Cucufate, to DNA studies) and (predominantly) engaging personal recollections and intergenerational stories.

We follow White from the outset of his Talha Tales adventure in 2014, when he pulls apart “a clattering string of anti-fly beads” to experience his first, bewitching taste of talha wine at Senhor Gato’s tasca (a small café-cum-wine bar). Palpable, his excitement leaps off the page when, “just hours before going to press,” a breakthrough revelation plugs a “yawning gap” in evidence for talha pots between Roman times and the 1600s.

Cool ancient technology again

The book is arranged in three sections. The first provides a deep dive into the background and culture of the pots/talha winemaking process and the modern-day renaissance of a thousands-of-years-old tradition, which had been hanging by a thread. White helpfully distinguishes talhas—the pots and gravity-led process—from other clay-made vessels and winemaking techniques from elsewhere in the world. He is at great pains to emphasize that amphorae (now a much bandied-about term) were used by the Romans only for wine transportation, not winemaking. Much more imposing, talha are necessarily made of sturdier stuff, so that, much like a Champagne bottle, they can withstand the pressures of the fermentation process.

In an insightful chapter titled “Talha: A Perfect Winemaking Machine,” White explores the beauty of talhas’ simple “funnel, atop a globe, set into a cone” design and functional, not just decorative neck braid. He conveys the economy of the “relatively hands-off and gravity-driven” winemaking process and highlights the advantages of the pot-bellied clay vessel over oak and stainless steel (for both the environment and the resulting wine). It is, White concludes, “one pretty cool piece of ancient technology, which ironically, just happens to be the world’s newest winemaking machine.”

As the former historian puts it, the book is chock-full of “esoteric geeky wine and cultural stuff” and covers the history of the pots themselves, the talha winemaking process, and the traditional grape varieties deployed. It was news to me that some talha grapes have highly distinctive DNA because, White reports, original wild European grapes that predated the last ice age did, in fact, survive during summer melts within parts of southern Europe, especially the interior and coastlines of the Iberian Peninsula and “most especially in Portugal’s Alentejo.”

White makes no bones about the fact that he has included “lots of speculation” where he has not (yet) found supporting evidence for theories, whether his own or those of third parties (and it is clear enough where this is the case). In a topic that (in no small part thanks to White) is only recently receiving the light of day, conjecture is not only understandable but a helpful means of exploring unresolved questions for writers and winemakers alike. White hopes it will spur others on to find the definitive answers.

That said, is there any such thing as a definitive answer? Chapters titled “To Pés or not to Pés…,” “A New Concept of Terroir and Grand Cru,” together with the second section (in-depth insights into the methods and philosophies of leading practitioners), highlight differences in varietal makeup, terroir, the source of clay, shape and size of talhas, and the application (or not) and composition of Pés (which coating mitigates wine egress and oxygen ingress). The producer profiles identify members of the Association of Vinho de Talha Producers (APVT), which—founded in September 2021 to protect and promote traditional styles of talha wines—favors lower sulfites, natural filtration, and only traditional grape varieties. Leaning away from tradition, others depart from the DOC Vinho de Talha rules about fermenting wines and leaving them on skins in talha until at least St Martin’s Day (November 11). They believe that varietal composition, terroir, and, in particular, the season, should dictate the length of skin contact.

These schisms make for a vibrant, multifaceted renaissance, which White captures well. Dubbing them “hybrid wine[s],” he observes that their makers are “spinning out entirely new concepts of wine” because, for example, only the press juice is fermented in talha (off skins) or wines are part-aged in barrel. Such departures are typically found among Portugal’s younger, well-traveled generation of winemakers, as well as incomers from other regions, about whom White perspicaciously remarks, “[S]ometimes it takes someone from the outside to see what is most special about a place.” On that subject, he gives a detailed account of the painstaking, pioneering work of Península de Setúbal-based Domingos Soares Franco (of José Maria da Fonseca) to revive Adega José de Sousa’s talha tradition.

Evocative tasting notes for each of the 17 profiled producers provide an invaluable insight into what to expect from talha wines/talha hybrids (indeed, individual producers, bearing in mind said schisms). White’s inclusion of his notes for Adega José de Sousa’s rare museum stock going back to 1940 are particularly welcome, highlighting the aging potential of top wines. The alcohol-by-volume data appears to contradict an earlier point he makes in chapter seven, about talha wines usually having “much lower alcohol.” There are plenty of lusty examples out there, even if a younger generation is leaning toward earlier picking, especially for vin de soif styles.

Although White’s producer coverage in this fast-growing field is comprehensive, I wondered why he had not included Piteira, a long-standing talha wine champion in the Granja-Amareleja subregion (who is mentioned in section one), or Sovibor in the Borba subregion, which lays claim to a sizable collections of 85 talhas. Sovibor’s extensive talha range includes varietal reds (even a Syrah), as well as traditional field blends and a petroleiro. White makes no reference to this mysterious petrol-colored category, which I believe to be local. He does mention two other traditional styles of pale red whose use has, since 2017, been regulated by law—namely, palhete wines (pale reds, with up to 15 percent white grapes) and “claret” wines (light-colored reds of no more than 12.5% ABV).

A talha renaissance and beyond

Like White, though drawn to the traditional lo-fi cellars and more rustic old-school wines, I welcome the “broad church” scene that is emerging. After all, the Portuguese are nothing if not consummate blenders. New-wave blends of traditional and modern techniques are producing some of the country’s most exciting wines. I could not agree more with White’s remark that the talha wine renaissance “is playing into the transformation of Alentejo. It finally has its own identity again, after the Aussie/Parker years,” when riper, oaky so-called international styles (and red wines) were de rigueur. The impact of talha goes well beyond the vessels themselves. Because of talha, producers in Alentejo and countrywide are questioning the use of oak and exploring other vessels for fermenting and maturation, whether made from clay, concrete, cement, or ceramic. (White’s account focuses exclusively on Alentejo, being talha’s heartland.)

Another exciting facet of the renaissance is the revival of traditional grape varieties, including field-blend vineyards, which are well adapted to Alentejo’s ever-warming, dry climate. With good acidity, especially with vine age, they tend to produce a “drier” (less fruit-led) wine style. White covers this important topic well in a chapter about traditional talha grape varieties. Given the dearth of varietal Portuguese wines, his observations about the viticulture, enology, and organoleptic propensity of individual varieties are most useful.

The third and final section of the book, by Jennifer Mortimer (White’s partner, who also produced the book), is described as about “[W]hat to eat, where to stay and what to do beyond drinking.” It offers bare-bones coverage and, says White, “[W]e plan on co-authoring other wine and tourism books that are more equally weighted in future.” That said, Mortimer’s brief section provides important cultural context (with suitably traditional, rustic recipes to boot) for this most gastronomic style of wine.

Most importantly, there is a higher purpose for the couple. Ten years ago, they were confronted by the grinding poverty of Alentejo’s villages, which, White poignantly reports, accounts for the closure of Senhor Gato’s tasca (where White experienced his first talha wine). Thanks to the talha renaissance, however, villages then “desperately sad” are “now thriving,” he reports, “and talha are driving that economy now, via food production, restaurants, Airbnbs…” Talha wines may have experienced a Dark Age, but in shedding considerable light on the whole genre, Talha Tales serves as both an invaluable record and a much-needed resource about an art and a tradition that was so very nearly lost.