Can fine wine weather the dire economic conditions, aks Chloe Ashton, as she rounds up third-quarter activities in wine salerooms around the globe and looks at what the near future might hold.

Global finances have taken a turn for the worse in 2022; the stage is macro-economic Armageddon, mixing the longer-term effects of the Covid-19 crisis, interest rate rises breaking an historic decade of lows, pending energy shortages, and cost-of-living inflation. Dark echoes of the 2008 financial crisis have already sounded amid traditional asset classes: At the time of writing, the S&P 500 is down 22 percent year to date, and the IMF forecasts an inflation rise of 8.8 percent by the end of 2022. What’s more, the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine generates further uncertainty in an already volatile environment—the world waits on tenterhooks.

Meanwhile, fine wine marches steadily on—an asset class seemingly on its own planet. Stephen Browett, chairman of UK merchant Farr Vintners, tells me, “Business is very good. It doesn’t seem that current economic pressures are having much effect on fine-wine buyers.”

Olivier Staub, chief investment officer of Cult Wines, concurs: “Our clients have not slowed down,” he assures me, “and we are seeing interest in fine wine driven by search for diversification from traditional financial markets, which are in turmoil.”

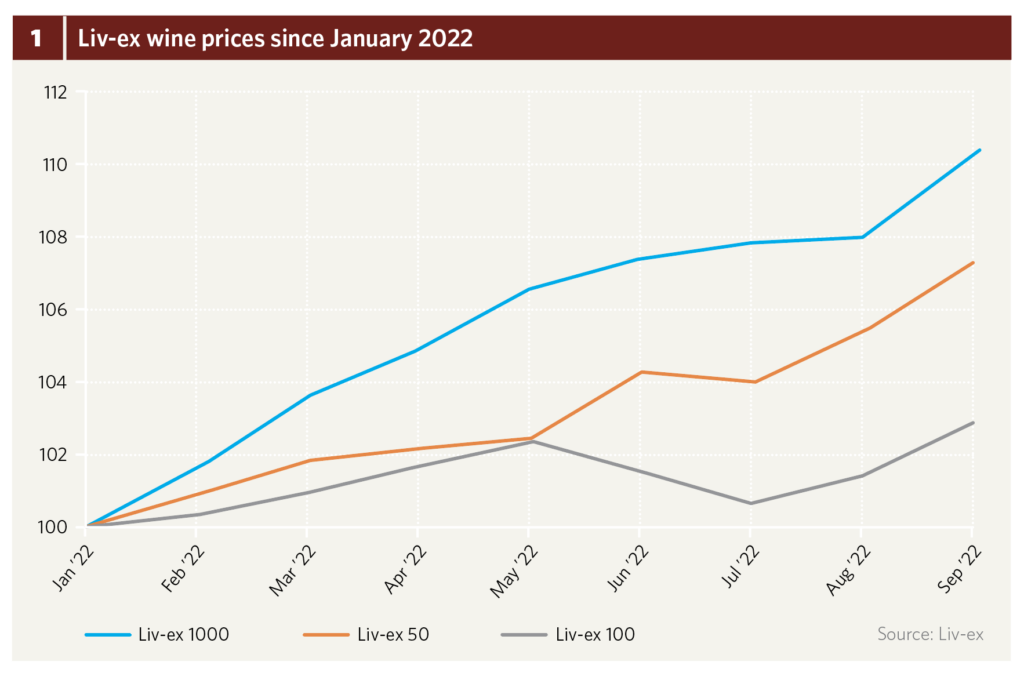

Indeed, the standard industry indicators for wine-market performance—the Liv-ex indices—have continued to rise, despite macroeconomic difficulties, throughout 2022. Fine wine’s most diverse measure—the Liv-ex 1000 index—grew by more than 10 percent between January and September this year, beating its three-quarter performance in 2021 by 1 percent. The narrower two indices—the Liv-ex 100 and Liv-ex 50—saw gains of 3 and 7 percent respectively, falling short of the 13 and 12 percent increases of 2021.

Will Hargrove, head of fine wine at Corney & Barrow, references this more measured defiance of fine wine against economic uncertainty: “I think [economic pressure] has brought a slight coolness to the market—but then it was a bit overheated.” Despite the positive direction overall, all three indices did falter during the summer months, before continuing upward to finish September on a high.

Even as the pound reached its lowest rate against the dollar since 1971 toward the end of this year’s third quarter, the now entirely globalized nature of fine-wine trading appears to have helped maintain a buoyant marketplace. Browett confirms, “The strong HK dollar and US dollar (these are our two main export markets) have been very good for export sales.”

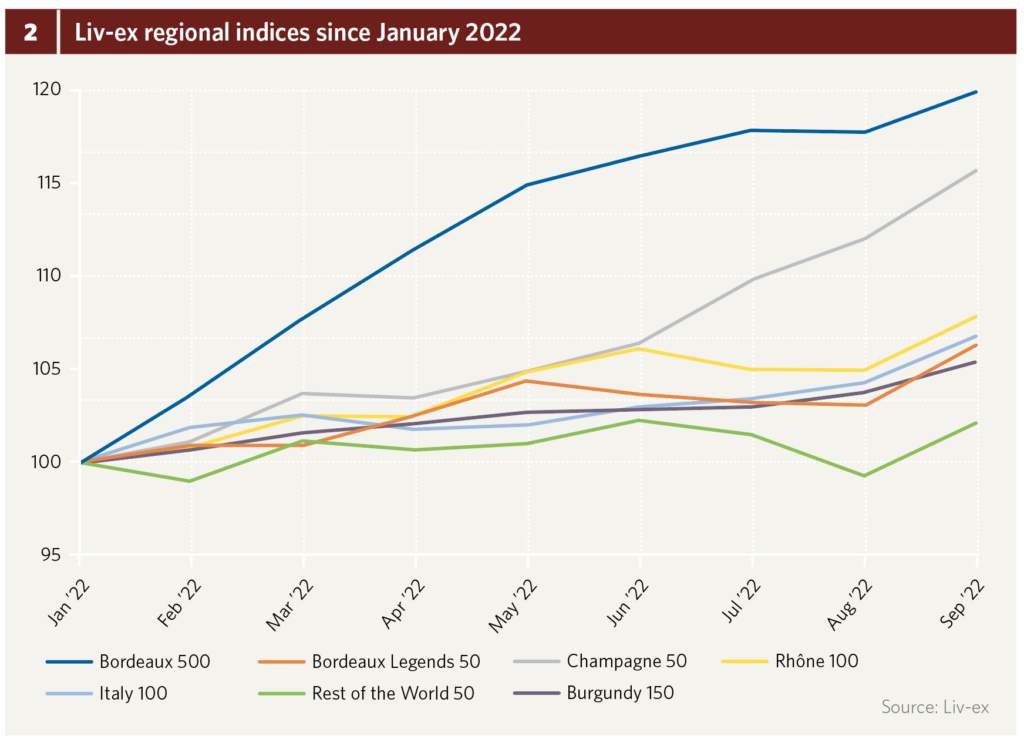

Regionally, the dominance of Burgundy and Champagne remains unchanged since last quarter’s report—Liv-ex’s corresponding regional indices have risen 20 and 16 percent respectively since the beginning of 2022. The frenzied demand for noble Pinot Noir shows no signs of stopping and, based on the supply-and-availability equation alone, may even continue, given the tiny crop awaiting Burgundy enthusiasts for the next round of primeur sales.

The upcoming vintage—2021—was hit by vinous hellfire; an increasingly common mild winter resulted in early budbreak, exposing vines to extensive damage from frost and hailstorms; then a wet summer threatened growing bunches with rot. As I walked around some of the vineyards on a visit to Burgundy in October, the physical gaps left by vines that vignerons have been forced to rip up due to disease or frost injury were a very real marker of how difficult the growing season was. In contrast, the few 2021s I managed to taste were classic and harmonious. Anthony Vertadier Mabille, associate director of Charles Taylor Wines, hails 2021 as “a truly Burgundian vintage” and “a return to the style of old, with good acidity and delicate flavors. But there’s not a lot of it,” he reminds me.

As for Champagne, releases of the 2012 and 2013—both excellent vintages—continue to propel demand forwards. When I visited Champagne shortly after this year’s harvest, the Champenois nonetheless spoke about the past 18 months with mixed emotions. There is a shared feeling of gratitude (and joy) for the impressive and persistent upticks in demand they have experienced since 2020.

And yet some feel frustration, since the region as a whole was bound by local association rules at the start of the pandemic, which enforced lower-than-average production volumes amid fears of having more Champagne than they could sell in a time of crisis. Ironically, the region is now experiencing a real shortage and having to exercise careful control on stocks leaving their cellars. One director of a major house told me, “This is a completely new era. We are not used to having to allocate our Champagnes, and now everything is already sold out through allocations”. Staub confirms that collector interest in Champagne continues to prove “very strong and widespread.”

All other Liv-ex regional indices maintain positive gains, averaging a 6 percent increase since January. Only the Rest of the World index struggles to keep up, sporting a 2 percent rise—compared with gains of 12 percent over the same period in 2021—and stumbling prior to both sets of Place de Bordeaux-based international wine releases in March and September. Theorizing with a Bordeaux négociant on future prospects for these wines as investments, we mused that while Covid created an opportunity for such wines to be discovered by more traditional drinkers, New World wines still lack the history and price-performance track record of the likes of Bordeaux.

Auction Update: Fine wine set for a record-breaking year

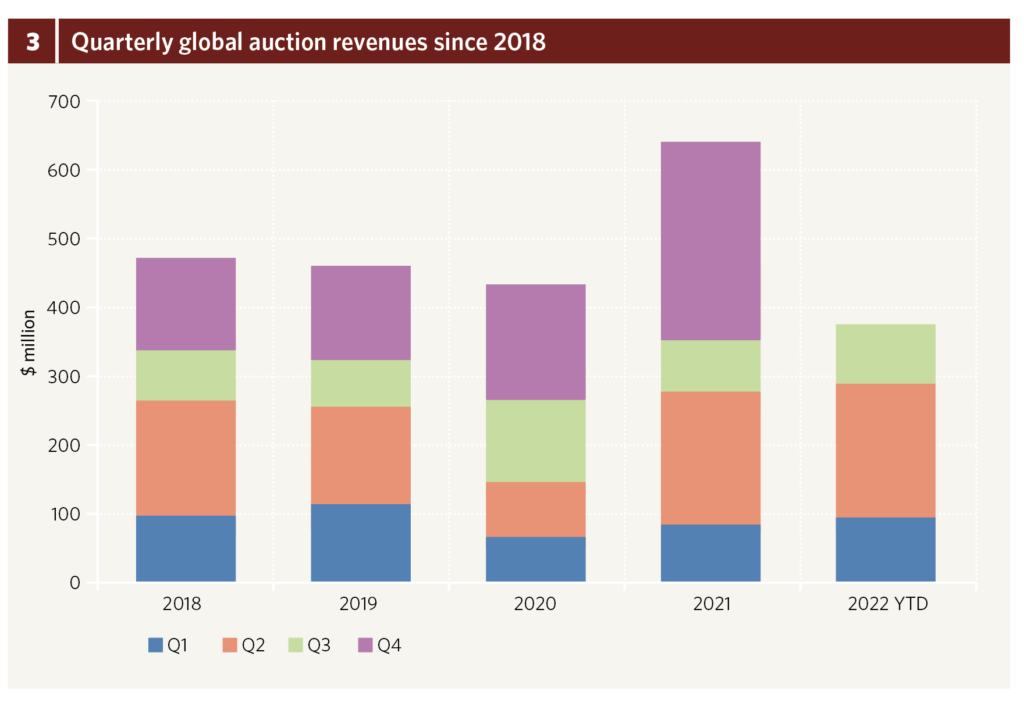

This year’s summer auction season generated revenues of just under $86 million, bringing the three-quarter total of 2022 to $375 million (fig. 3). These impressive numbers put 2022 ahead of 2021 year to date by $21 million (or 6 percent) and suggest the year is on course to be yet another record-breaker for auctions.

Online-only sales have also increased year on year, both absolutely and proportionally: Fine wines auctioned online through major houses up to September 2022 represented $55 million, or 14 percent of all sales, compared with 2021’s three-quarter digital total of $40 million (11 percent).

Speaking to Alfonso de Gaetano—founder of digital auction platform Crurated—online sales appear set to continue their growth, particularly among younger audiences. He notes, “Digital platforms are now making it easier to buy wines and engage with winemakers that were often challenging to gain access to. They have changed consumer behavior, which signaled to fine-wine producers that they needed to rethink traditional distribution and more openly embrace the digital world.”

Relating to the online space, recent conversations with several auction leaders have yielded a collective, twofold theory to explain the strong ongoing performance of the global gavel. First, this diversification in sales methods has made the auction world more competitive and far more accessible than it has ever been before, both to new kinds of consumers and to collectors living at a distance from physical sales. Second, the digitalization of auctions and wide publication of fine wine’s rising demand may well have encouraged more private collectors with saturated cellars to seek liquidation, filling salerooms with stock and further fueling the demand cycle.

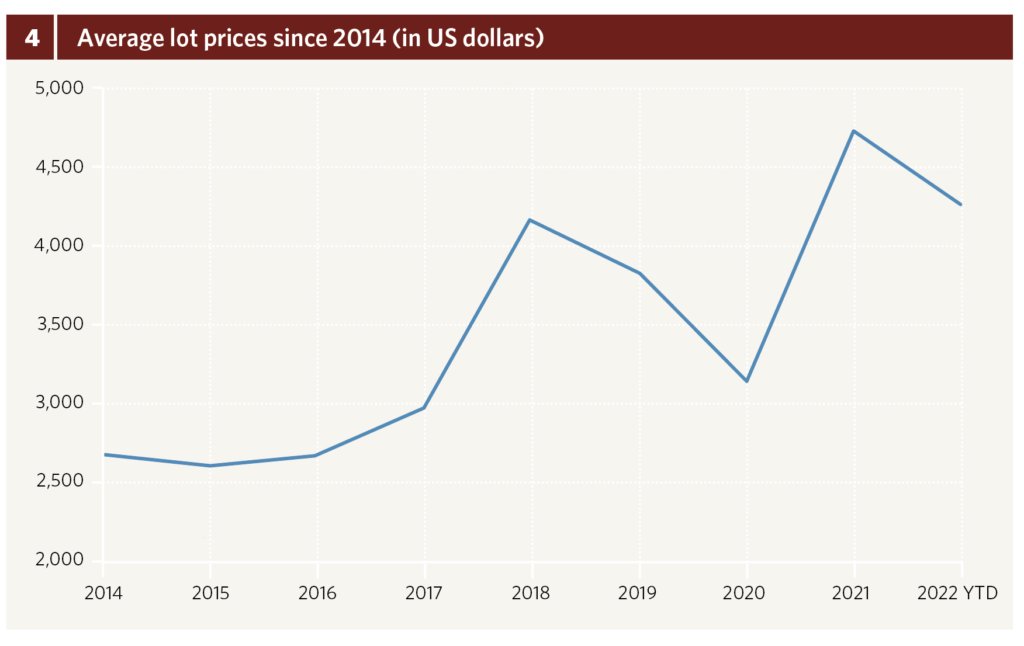

While it’s a blessing to support healthy bottom lines overall, this may nonetheless have affected hammer-price elasticity. A review of average lot prices since 2014 shows a first peak in 2018—the last time many gavel records were reached—and another last year, matching an unprecedented 12 months for wine prices in the secondary market (fig. 4).

Prices at gavel closure in 2022 thus far are not consistently stretching beyond high estimates—a possible indicator that engagement is beginning to soften. Two Swiss-based houses, however, argue the contrary: Julie Carpentier, co-founder and deputy director of Baghera, says, “We have witnessed strong demand from the international clientele for fine wines during August and September, especially from Asia-based wine collectors.”

Based in Zurich, Marc Fischer is similarly positive. Referencing his house’s summer auction and a vertical parcel of Armand Rousseau’s Chambertin in particular, he tells me, “This collection of super-rare Burgundies came under the hammer, and prices reached stratospheric levels.” He nonetheless observes “less interest from UK and Hong Kong buyers” at present.

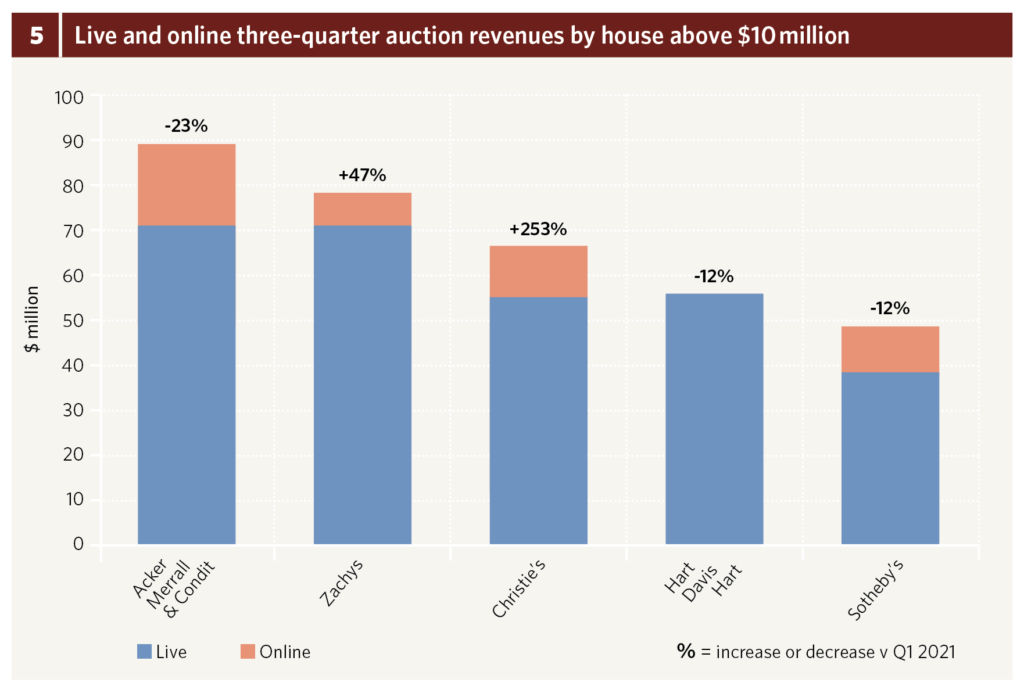

Sales achieved by the “big five” auction houses make up 90 percent ($336 million) of three-quarter revenues for 2022 (fig. 5). While Covid-19 leveled the playing field for auction sales figures in 2020 and 2021, the resurgence of these top-performing houses suggests that decentralization of demand was but temporary. Indeed, based on figures to September 2022, the next best-performing auction outfit—Los Angeles-based Heritage—lies a $40-million gap away from 2022’s global auction number 5, Sotheby’s.

Auction Goliath of the USA, Acker Merrall & Condit remains on top of the podium, achieving a three-quarter sales total of $88 million. Though still in first place, numbers are down 23 percent on the equivalent period for 2021, contrary to silver medalist Zachys, whose $77 million earned between January and September 2022 increases its three-quarter performance year on year by 47 percent. Indeed, the gap between the two houses has reduced significantly—at the same time last year, Acker’s running total represented more than twice that of Zachys.

Commenting on the house’s strong performance thus far, Charles Antin, Zachys’ head of wine-auction sales explains, “One of the strongest drivers of [Zachys’] successes in 2022 has been the quality of the collection as a whole.” Referencing August’s auction, The Unicorn Collection—the summer season’s highest-earning sale—he notes, “When the dust settled, The Unicorn grossed over $16 million and was Zachys’ highest average lot value ever at nearly $20,000; half of the lots on offer sold for over $10,000, and 246 bidders from around the world placed well over 5,000 bids. Half the lots in the auction sold over the high estimate, and $3 million of bids were placed live in the room.”

Christie’s boasts revenues achieved between January and September 2022 of $66 million, exceeding its three-quarter total of the equivalent period last year by more than three and a half times. The outstanding results move the international house up from sixth to third place relative to the first three quarters of 2021. Harnessing a market for online sales has no doubt boosted Christie’s figures, but Antin’s sentiment on the quality of an auction’s presentation (and perhaps, personality) resounds in Christie’s successes, too.

Long-term relationships with top collectors or producers have clearly done both houses a good turn: Five of Christie’s 13 sales between January and September 2022 were single-cellar collections, procured and curated with one private owner at a time, while a further three sales feature blocks of single ownership. Meanwhile, Antin makes mention of Zachys’ close relationship with Fred Schrader (of Schrader Cellars), and the advantage of being able to offer “a massive amount of his namesake wines straight from the winery and his personal cellar.” Wine collecting has always been deeply personal, but I would wager that the need for a human story behind a selection of bottles is accentuated after the global health crisis, as well as in times of turmoil.

The only consistent exception to this appears to be wines from Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, which continue to dominate leading hammer prices (representing 35 percent of all top lots disclosed to September 2022) regardless of their previous owners, suggesting that any wine benefiting from such gargantuan demand simply has no price ceiling.

At any rate, fine wines with great stories told around them, or names so rare that to own a bottle would tell a story in its own right, may well remain protected from the financial turbulence facing the world at present. As for the wider fine-wine market at large, Staub highlights that “customers at the top of the wealth pyramid are unaffected and continue to buy and consume great wines.”

He adds, “Some are even benefiting from the current situation (high energy prices, strong demand for certain products post-Covid), and pure investors are driven by the search for stability and de-correlated assets to protect their wealth against volatility and inflation.”

While this may ring true in the long term, recent discussions with a handful of collectors suggest a momentary market freeze might hinder price performance in the coming months, caused by distraction amid all the uncertainty rather than any more ominous or persisting affordability issue. Such an occurrence might prove a necessary evil to recalibrate the market for certain icon wines and give those that are undervalued a chance to catch up—before wine prices take flight once again.