From Ancient Greek and medieval strictures on serving sizes, to modern anxieties about serving temperature, Stuart Walton negotiates the elaborate history of wine etiquette.

The wine connoisseur is a figure of fun in the popular imagination—a floridly complexioned old soak in a bow-tie, or perhaps an undernourished aesthete with a developed proficiency in the poetic analogue but only the most glancing familiarity with human warmth.

If expertise is directly predicated on the intricacy of a subject, wine has only gained in professorial potential, the more it has ramified through every corner of the two thick bands on either side of the Equator in which its raw materials will thrive.

Add to the multiplicity of wines the tantalizing fact of their annual variation, and another layer of authority needs acquiring, at least for those bottles that are intended to develop through cellaring. Gin doesn’t change with keeping, other than that the level in the bottle goes down.

Wine etiquette: Drinking properly

An accomplished knowledge of wine is in itself a development of the need to drink it properly. Its extravagant diversity, even within surprisingly small sub-regions, already demands application to a whole range of different social and culinary contexts, and not just in its homelands.

The further away enophilia implanted itself from any immediate connection with the farmers, vintners, barrel-makers, and brokers who guaranteed its production and export every year, the more assiduously it applied itself to its task. Every wine has its own back-story, its heritage, and its proper place on the table, and the elaboration of a connoisseurial approach to it, already in evidence in the classical Greek period, impressed on its drinkers the need to treat it with respect.

The Athenian symposium began, whatever comic capers its proceedings eventually led to, with the judicious prescription of measure—how much wine was to be drunk, and mixed to what proportions with water. The pace of consumption had already become far more of an ethical nicety in wine than it ever was with beer.

In the Problemata, a vast collection of analytic texts once partly misattributed to Aristotle, it is observed—perhaps surprisingly—that drinking wine from large cups is less likely to lead to intoxication. The theory was that more of wine’s intrinsic heat, one of its principal humoral properties, is vaporized in a larger receptacle, and so less of it goes into its imbiber’s bloodstream.

Medieval etiquette: Size and speed

By the medieval period, such necessities were being put on a systematic footing. An eleventh-century medical treatise by the Baghdad physician Ibn Butlan (1001-1064), Tacuinum Sanitatis (The Maintenance of Health), draws a direct parallel between the size of the cup and the rate of intoxication. Particularly bitter wines, where unavoidable, should be served in larger cups, precisely because they will encourage the drinker to consume more slowly.

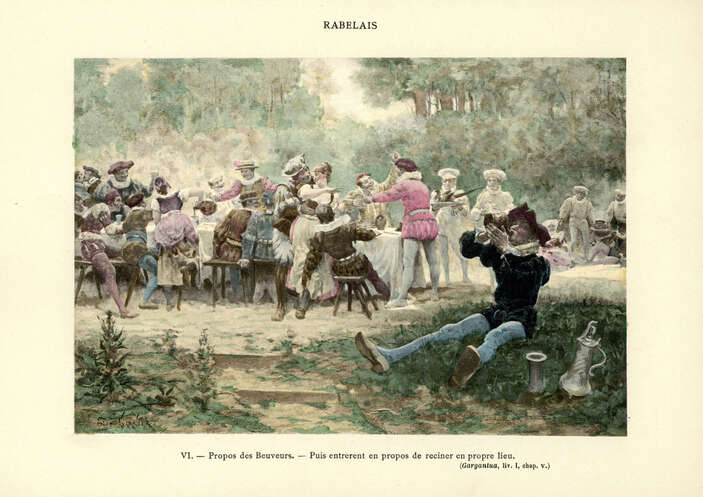

What is fascinating about this is the notion that, contrary to what the Gargantuan yahoos of the symposium may prefer, undue inebriation is particularly to be avoided when drinking wine. An even surer way to stay clear-headed than cup size—and one with more obvious lasting scientific assurance—is to drink sparingly.

All the medieval writers emphasize this: the first book of the Canons of Medicine by Ibn Sina (Avicenna) advises it. It also cautions against drinking more wine before the body has finished digesting food, which process it can only calamitously impede.

Better to drink beforehand to prime the alimentary system—but only shortly beforehand, since prolonged drinking on an empty stomach is also known to be damaging. Drinking wine with excessively acidic, spicy, or salty tastes creates a humoral melee.

Wine etiquette and the connoiseurial temperament

The connoisseurial temperament arose from these strictures precisely because it was a way of drinking in a measured, evaluative and appreciative way, rather than with the instrumental purpose of getting drunk.

Azélina Jaboulet-Vercherre, in her excellent monograph, The Physician, The Drinker, and The Drunk (2014), points out that the etymology of “gourmet” derives from the 14th-century French gromet, a wine-merchant’s assistant, somebody who has learned to taste wines, rather than simply consume them. It would be another three centuries before such specializing delicacy extended its purview into the realm of food. It is intoxicating drink, first of all, that needs the restraining hand.

In the present day, when overt or accidental drunkenness are still a faux pas, and a coin tossed in the air at a city brasserie is likelier to come down on a gourmand than a gourmet, there is an even greater accretion of mannerliness around the drinking of wine.

There are many more faux pas than vrais: Clutching the glass by its bowl like an ape gripping an orange; leaving a chain of greasy lip-marks all about the rim; holding the poured bottle in a throttling clench on its neck; over-filling the glass; over-filling your own glass; adding ice.

A writer on Martha Stewart’s website reports that the most popular wine etiquette-buster among American drinkers is quaffing white wine at room temperature. One hardly knows where to look.