As part of a season of Hellenic-themed pieces, we have gone back to the archives for a book review first published in WFW63 in March 2019, in which Stuart Walton reveled in a magnificent compendium of scholarship on the subject of the symposion in Ancient Greece.

The fact that the symposion, the male drinking party that has come down to us through the texts of Plato, Aristotle, Xenophon, and others, has become such a key feature of cultural studies of Greece in the archaic and classical periods is due in no small measure to the researches of Oswyn Murray and a growing band of like-minded scholars of antiquity. It is, to be sure, insistently present from depictions in texts such as the classic Symposium of Plato or, indeed, from the ruminations on its social significance to be found in the same writer’s Laws and in Aristotle’s Politics, but it is only over the past 40 years or so that it has assumed a pivotal role in a fully rounded understanding of ancient Greece.

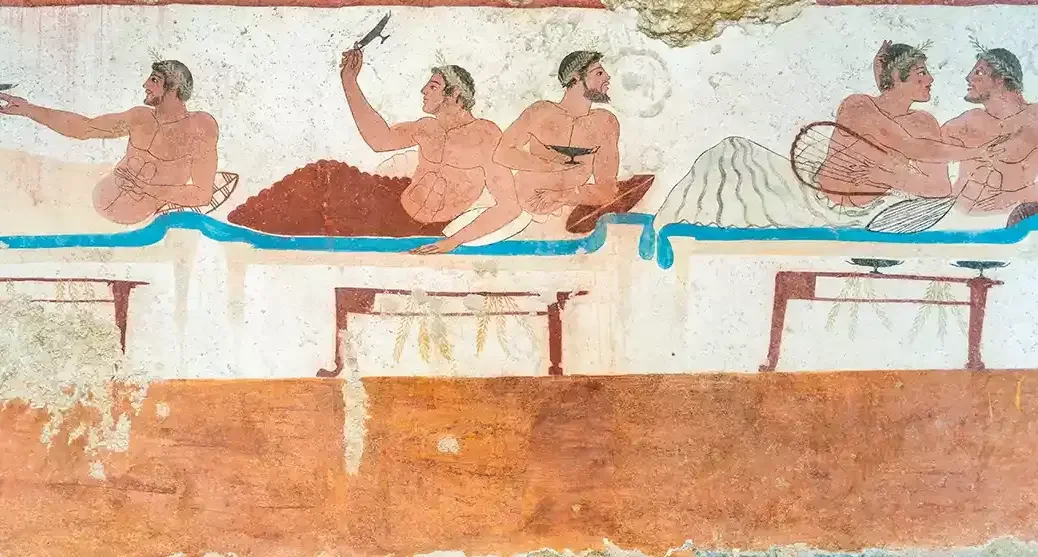

Evidence for its structure, its ceremonial tone, and the kinds of behavior it licensed and encouraged exists not just in the extant literary sources but in black- and red-figure pottery, which shows us the physical dispositions of the participants, as well as their emotional moods, their degrees of drunkenness, their inevitable moments of gastric turmoil, and their sexual conduct, too. Despite its long career in classical historiography as little more than a symptom of the uproarious self-indulgences that a certain class of lusty males in Athenian society permitted itself, Murray’s reclamation of the symposion as an institution restores it to its role at the heart of harmonious social organization, a function of which the philosophical writers of its day had been trying to tell us all along.

Remote origin

The remote origin of the phenomenon lies in the development of culture itself through the unequal distribution of surplus resources, primarily agricultural resources. When fruit and grain can be turned into alcohol rather than remaining solid sustenance for feeding the whole community, they beget a social class that can afford to consume it. In the heroic age, the world of Homeric legend in the 8th century bc, such consumption came to be ritualized in the form of the victory feasting of warriors. It was a reward for success in battle, and it helped cement the ties of military camaraderie among its participants. Under the influence of cultural habits from farther east, from the Persians in particular, the feast took on a tone of orientalizing luxury, not the least symbolic marker of which was the transition from traditional sitting at a banquet table to the more lordly posture of reclining.

By the zenith of Athenian culture, the symposion had taken on a fully elaborated panoply of ritual practices. It took place in a domestic space reserved for the purpose—the andron, or men’s room—just inside the entrance to the house, which was furnished with couches around all four sides, with low tables before them. The symposiarch, or host, was responsible for decreeing what was consumed—the precise proportions of wine to water, its mixing in the krater, and the overall quantity that would, in theory at least, be drunk.

A series of entertainments was laid on, consisting of sung poetry, recitals, arguments, and debates, which would proceed in a convivial manner until the point at which merry loquacity began to give way to drunken cacophony. Participants reclined two to a couch, each pair typically consisting of a young well-born man and his older companion, who was very often his lover. The wine was poured by slave-boys in a state of nakedness, their onerous duties customarily extending to bearing a deal of inebriated groping by the guests, as well as holding their heads when they needed to vomit.

At the end of the symposion, in a ritual that became an integral part of the proceedings, the guests would debouch into the streets, where they committed acts of drunken affray, vandalizing property and roughhousing with passers-by. Although these excesses, known as the komos, often incurred civil penalties, they were seen as a socially indispensable means of displaying aristocratic power. The sheer gratuity of it was self-justifying. “We smash your door in because we can. Plus we’re rat-assed. What you gonna do?” Nothing about that ritual, other than its exclusively class-bound nature, ought to be unfamiliar to the study of male drinking cultures in subsequent ages.

Cultural and ethical dimensions

It is a fundamental element in Murray’s approach that he situates his sympotic studies within the context of the history of mentalities, and particularly the history of pleasure. The pioneering work of Michel Foucault—whose multivolume History of Sexuality (1976–2018) includes sustained reflection on the hedonic practices of the Greco-Roman world—is an ever-present resource in this approach, but Murray’s work has been valuable for its synthesizing a whole range of aesthetic and philosophical components of that world, in order to build up a three-dimensional picture. Historical materialists may balk at his suggestion that the development of pleasure, as indeed of culture as a whole, can be divorced from the socioeconomic and political contexts in which it arises and flourishes, but Murray espouses the view of the Swiss cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt that culture is precisely that which is variable and spontaneous in human affairs, and as such largely discrete from the general historical process. That said, he also inherits Ernst Gombrich’s notion that the human instinct for order is observable in the cultural manifestations, as much as in arrangements of the civil polity, of each era.

In an ethical vein, Murray rightly situates the history of pleasure in the light of the development of morals. There is no true pleasure without external social disapproval. Indeed, pleasure gains much of its force thereby. In an elegant dialectical point not often found even in the most scrupulously materialist of thinkers, he suggests that the guilt context to which Christianity, flexing its muscles eventually on the imperial scale, would subject the practice of hedonistic indulgence contributes to the calculus of pleasure precisely by sharpening the notion of sin. In any case, the mystical Christian traditions were hardly unfamiliar with the idea of God’s presence as the most sublime intoxicant of all—a current that has its own distant origins in the Orphic conception of the afterlife as a state of eternal drunkenness. Henceforward, though, the after-effects of the symposion, the dreaded “morning after” that haunts the drinker’s imagination, would be the material evidence of shame, though even the hangover would receive its rhetorical celebration in the odes of Zhou Dynasty China.

Undergirding social equilibrium

With great subtlety, Murray teases out from the classical texts the distinction between immediate sensual pleasure and the emotional state that it engenders and sustains. Euphrosyne— the Greek term for the feeling that combines active delight and a profound contentment that all is right with the world—is located not in feasting and drinking in themselves but in the state of mind that results from them. Strikingly, there is virtually no other image of the pleasurable life than the symposion in Greek thought until Aristotle, and even in his writings, it remains the preeminent paradigm. Plato may have been concerned to establish a strict hierarchy as between the physical and spiritual occasions of virtue, but there is scarcely a metaphor of pleasure anywhere in his work that does not derive from the symposion, its eating, drinking, sex, poetry, music, dance, and conviviality.

If the practice of egalitarian bonding through alcohol, particularly within single-sex groups, has become the very emblem of social fragmentation in the present day, that continues to exemplify the practice noted by Murray whereby medical and sociological approaches to alcohol tend to see its use as symptomatic of dysfunction, whereas the anthropologist notes its longue durée in virtually all societies, the undergirding of social equilibrium that it insures, together with those transformations of consciousness that enable its users to reconcile themselves to a world that otherwise stubbornly refuses to match up to them. According to Murray, the rules that obtained within the Greek symposion do not, despite what some historians have suggested, make it a microcosm of the well- ordered polis, precisely because the secure ordering of society turns out to depend on methods of release that propose an alternative to it.

This magnificent volume brings together a body of work stretching over nearly 35 years. If there are obvious repetitions of argument and reference between conference paper and anthology chapter for the reader who diligently walks its 400-page path, these are inevitable given the range of disparate contexts in which these items first appeared, but they serve rather to reinforce the most salient historical points than to seem at all superfluous. Thus, we continue to learn new aspects of how wine was drunk, the purposes to which it was put, and the resonances such cultural practices have for current investigations into the history of pleasures—or indeed the histories of pleasure, as Murray prefers. The book is a handsomely produced testament to a lifetime’s disciplinary rigor, no less than is the happy news that, rather than wasting his retirement repining into slippered and pantalooned quiescence, its author makes his own cider on a farm in north Oxfordshire. From the opposite corner of the continent, across the vasts of time, one hears the distant cheers of Athenian revelers.

The Symposion: Drinking Greek Style: Essays on Greek Pleasure 1983–2017

by Oswyn Murray

Published by Oxford University Press 480 pages; $124.95 / £90