Discontent with wine tax was one of the catalysts for the French Revolution, says Stuart Walton, who wonders if taxes on pleasure can ever be justified.

The seismic events of July 1789 in Paris have tended to turn on one historical focus: the storming of the Bastille, the largely empty fortress that nonetheless symbolised the monolithic power of the ancien régime.

Its liberation bequeathed a Fête Nationale Française to French posterity, celebrated on the 14th of the month every year. More momentous, however, were the disturbances at the peripheries in the three days prior to this date, when the hated toll offices at the city gates were overwhelmed and goods coming into the capital forcibly granted free passage.

Paris: A city that ran on wine

By far the most significant of these was wine. It is no exaggeration to say that Paris ran on wine. From the cellars of the aristocracy to the daily draught of the manual workers, virtually everybody drank it.

Alone among alcohol types, wine’s social reach extends from an elevated cultural asset of the privileged to the rough-and-ready staple of the most impoverished. The economic effect of its social ubiquity was such that the wine tax levied at the city boundaries was responsible for more fiscal revenue than that on all other commodities combined.

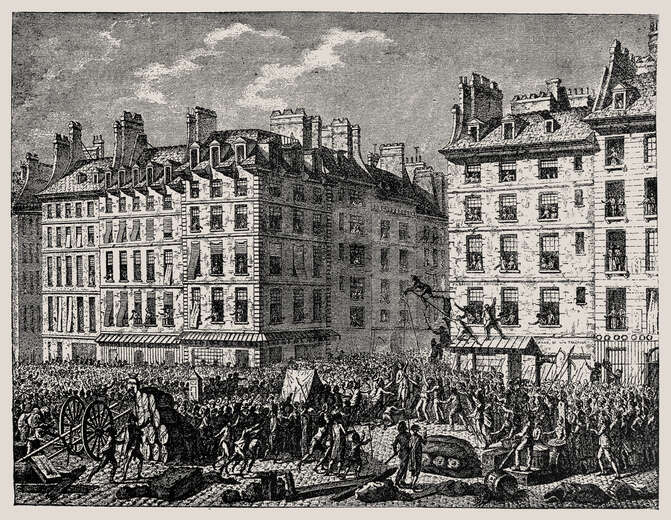

In the pre-revolutionary era, the price of a barrel of wine effectively trebled as it passed through the toll-barriers on its way to the Parisian markets. Over a turbulent four days in that broiling July, the tollgates were stormed by insurrectionary crowds armed with clubs, agricultural tools and whatever else was to hand.

Not only were customs officers prevented from inspecting the cartloads of wine that were waiting at the gates but, as they entered the city tax-free, many of the barrels were opened in celebration, with cups of wine being handed round in the street. Cacophonous music broke out to accompany the improvised bacchanal, the festive street scenes illuminated by the dancing flames consuming the tollbooths.

The intoxication historian Noelle Plack notes that the role wine played in the storming of the tollbooths, and other rebellious acts during the onset of the Revolution, has led many historians, beginning with the nineteenth-century writer Hippolyte Taine, to characterize the insurrectionaries as drunken mobs who had no particular political aim in mind, but were only content to enjoy a spot of inebriated chaos in the manner of the medieval feasts of misrule.

This, she argues, is to miss the point.

If a fundamental instrument of popular pleasure such as wine is taxed beyond the capacity of ordinary people to afford it, the latent fury that builds up must find an expression.

Among these provisions, wine enjoys a unique dual status as both a staple commodity and means of sensuous release. How else would the forcible abolition of the tax system on wine be celebrated, other than by drinking wine?

It would take the Jacobin chiefs of staff another two years to abolish the principle of taxing consumer goods, but by 1 May 1791, wine was no longer subject to the toll.

Extended, fully lubricated celebrations naturally accompanied the enactment of the new legislation. There is a concrete difference between the demand for constitutional liberties and the equally urgent imperative for reasonable access to material goods.

“[B]y articulating demands in terms of consumption,” as Plack puts it, “ordinary citizens insisted that liberty and equality be made material, physical, and substantive—in essence, that they could be tasted.”

Principles of taxation

The principle of taxation, excise duty in particular, rests on the notion that governments have a right to impose a levy on citizens for the consumption of commodities that are not, strictly speaking, a vital necessity of their survival.

Since many commodities that are even more indispensable, such as fuel for heating and cooking, are also taxed, the mildewed concept of the luxury item, the indulgence, has been rendered inoperative.

In the UK, the so far successful resistance to the idea of taxing books and other publications has rested on the idea that such an impost would be a tax on knowledge, which ought to be a sacrosanct right of the free citizen. The tax on wine and other drinks is a tax on pleasure, on recreation, on those increasingly circumscribed periods of escape from the common round that people are still just about permitted by extended working hours.

Taxing intoxicants is, in any case, an ambivalent instrument at best. Is it, as with tobacco, intended in the spirit of dissuasion, of making a lethal habit unaffordable? Or is it, as with wine, a means of coercively inviting consumers to pay again for the blameless activity of enjoying themselves?

The Paris events of July 1789 brought these countervailing forces to the forefront of social conflict. By burning the tollbooths and opening the barrels, the people insisted that the enjoyment of wine ought to be a direct contract between its producers and its consumers, with no intervening authority dipping its grasping fist into the transaction.

They would win for themselves a famous short-lived victory, but one that resonates through all subsequent ages.