It’s not something I do often on a Monday evening in London,” said Jean-Marc Roulot with a serious smile as he presented a vertical of Meursault Tessons to a small group of Burgundy devotees at Noble Rot in Soho, London. Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir is a vineyard close to his heart. “Domaine Roulot was built on village wine, and Tessons is the greatest village climat in Meursault. The premier cru story came later.”

Six generations of the Roulot family have produced wine in Meursault since the early 19th century, but it was not until the 1950s and ’60s that Guy Roulot began creating the domaine, buying, renting, and planting village parcels. He was among the first producers to make separate bottlings of village lieux-dits, in a departure from the common practice of making a village blend.

The domaine has seven village parcels, among which Tessons is easiest to spot by virtue of the rather grand vignerons’ huts scattered across its east-facing slope. Roulot’s clos, within the 4ha (10-acre) climat, was planted in the 1950s. “Tessons is the most representative of the village Meursaults. It faces full east, while Luchets, for example, turns slightly to face north, and has benefited from the warmer summers. Tessons is always picked before Luchets and is riper. Tessons has verticality but is generous and complex.

“It is situated at 260m [850ft], continuing a line with the premiers crus, and I feel it is of premier cru quality. When they made the classification [begun in 1935], maybe there were more powerful people with premiers crus.” Historically, Tessons has been highly regarded, rated as deuxième cru before the current AOC classification. Roulot, however, is not about to upset the appellation applecart. “I don’t want to change things. If you start this, producers of Bourgogne will want a village appellation. The classification was well done at the time, but Tessons is the most faithful village wine in every vintage.”

Perrières palate cleanser

There were murmurs of assent from the damp diners gathered in the cozy first-floor room of the restaurant. Having braved a torrential April downpour, we were cheered by a glass of Michel Gonet Blancs de Blancs 3 Terroirs 2017 on arrival. Light and biscuity, this is Noble Rot’s house Champagne, and while drinking it, I took a moment to catch up with fellow MW Mark Andrew.

Noble Rot in Soho is Mark Andrew’s and Dan Keeling’s second restaurant, launched in September 2020, in the wake of the immensely successful Bloomsbury Noble Rot. The restaurants share an old London feel, housed in buildings that resonate with history. It’s easy to imagine Samuel Pepys writing his diary in a dim corner over a glass of ale—with some license, since the buildings date from the early 1700s.

“I love old buildings and how they make you feel,” says Andrew, “and how this chimes with the food and wine we like, which brings together tradition with new ideas and innovation.” Soho’s Greek Street is one of those pockets of old London that escaped the bombs during World War II, and many will remember this building as Hungarian watering hole The Gay Hussar, a characterful restaurant of modest cuisine and crimson velvet drapes. This former haunt of politicians and journalists has become another layer in the walls and memory of the place. “We are just custodians of these buildings,” says Andrew. Newly minted as Noble Rot, it still attracts creatives, including Ian Hislop, who hosts a weekly lunch meeting for Private Eye in the private dining room.

Keeling and Andrew seem quite unstoppable, as a third Noble Rot opened on April 6 in London’s Mayfair. Mayfair? “We wouldn’t open a restaurant next to Annabel’s. Not us at all. It’s in Shepherd’s Market, with the right feel,” says Andrew.

Once we were tucked up at our tables, an unexpected 1988 Meursault Premier Cru Les Perrières was poured. “I brought this as a surprise gift for the end of the meal,” Roulot tells us, “but I decided it would be better as a palate cleanser before Tessons.” There was a gentle hum of appreciation.

The 1988 vintage was actually made by Franck Grux, Jean-Marc Roulot’s cousin. Following the death of Guy Roulot in 1982, at the age of just 53, Californian Ted Lemon (who went on to establish Littorai in his home state), and then Grux, held the fort for Roulot, who was busy pursuing a career in acting. But Grux was pinched by Olivier Leflaive, and Roulot retuned to look after the élevage of the 1988 vintage. In common with most white-Burgundy producers at the time, Domaine Roulot bottled whites after 12 months. It is practical to empty the barrels to receive the next vintage, but extending the élevage was among the first significant changes Roulot made at the winery, together with a move to an organic approach in the vineyards. “I had no choice,” he admits. “In ’93, Perrières had finished the malolactic fermentation but still had sugar.” Happily, he was rather pleased with the result. “I found the longer aging integrated the acidity very differently, and the texture was more silky. If you bottle at 11 months, you close on the fruit and you lose something.” Roulot had an inkling of the benefits of long maturation from tasting Dominique Lafon’s wines, and to begin with, Roulot also used two sets of barrels, but it was not long before he moved to using stainless steel for the second winter.

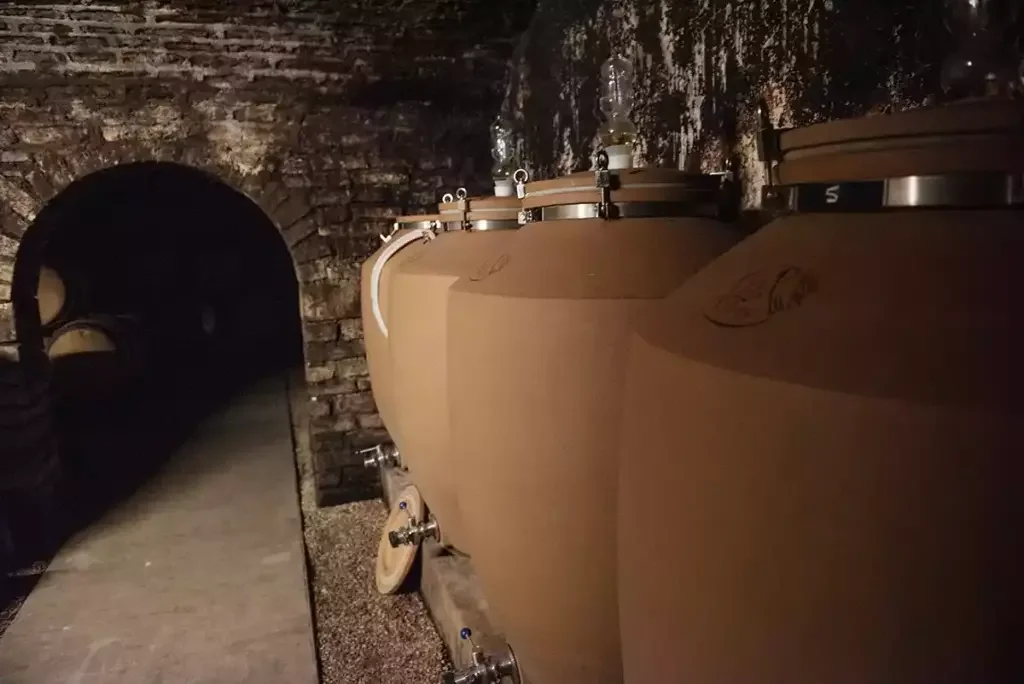

Over the past 20 years, extended maturation has become a widespread practice at serious domaines, with stainless steel the most popular choice for the final six months. But many are experimenting with other materials for the fermentation and initial élevage. Roulot uses some 500-liter sandstone vessels, together with oak barrels, concrete vessels, and Stockinger foudres. “I like the reductive character of sandstone but also the energy it gives.” Tessons, however, has no lack of inherent tension and doesn’t get the sandstone treatment.

Quintessential white Burgundy

Palates primed, we were ready for a flight of eight Tessons. My favorites were 2017, 2009, 2007, and 1996. The 2017 was the most joyous, captivating for its youthful fruit and energy; and the 2009 was the most surprising—sumptuous but elegant and energetic.

The hot 2009 season produced some rather heavy, rich whites with soft acidity. An extensive tasting of 2009 I arranged four years ago showed that some 2009s have slimmed down, and where there is sufficient acidity, they are now quite nicely in balance. Others, however, were slightly oxidative and tired. Among the lineup were a few gems, including the Tessons from Jean-Philippe Fichet, which outperformed many a premier cru. Roulot’s Tessons is another gorgeous example of 2009. “We harvested early,” he recalls. “Maybe people were less concerned with harvest dates in the late 2000s than we are now.” Burgundians go on holiday in August; holidays that were cut short in 2018 and 2019. By 2020, most had reluctantly adapted their traditional schedule, only for 2021 to offer a reprieve.

As Roulot points out, “The window (for picking) is very, very narrow in early September because the days are longer, while at the end of September they are colder and shorter.” One day has far greater impact on maturity. In 2009, the high temperature in August continued into September, creating quite wide variability in style.

“People arrived in the cellar and said this vintage (2009) would be dead in two or three years. No, no, no. The main thing for aging potential is healthy grapes, and my 2009s were very healthy. 2010 had botrytis. I prefer the profile of my 2009.”

For my part, I like 2010s for their vigorous intensity, but parts of Meursault were hit by an electric storm shortly before harvest. Anything with botrytis “turned” very quickly. Good deselection of botrytis was important in 2010 and, for that matter, in 2008.

2007 hit the top of my leader board, vying with 2017: quintessential white Burgundy, stylish and refined. Some white Burgundy is still worth waiting for, and this is an eloquent example. 2007 was a fine-boned, racy vintage that has matured with grace. “Patience is needed,” says Roulot. “We have lost the culture to age wine.” True, but Mark Andrew also makes an important point: “There has to be trust. We started working with Domaine Roulot in 2017 because we were totally confident in the wine’s aging capacity, but premature oxidation of white Burgundy is still an issue.” Andrew and Keeling are at the sharp end—not just in their restaurants but as fine-wine importers. Andrew nods toward the table beside us. “Some people here spend tens of thousands on white Burgundy and will drink them within two or three years because they are worried about premox. It’s about rebuilding trust.”

The 2007 shows how this trust can be rewarded, as does the delicious 1996, a wine closing in on 30 years in bottle. “1996 was my favorite vintage after 1989,” says Roulot. 1996 was a vintage beset with problems of premox—possibly because of a long delay before the malolactic, during which time the wines were unprotected—but when the wines are pure, this is a fine vintage, and this Tessons is a lovely example. Roulot had brought a bottle, because the magnums were spoiled due to a problem with the cork—but he didn’t specify whether the issue was TCA or oxidation. Thank goodness cork has improved over the intervening years. Nevertheless, several well-known producers, including Lafon and Leflaive, have moved over to Diam closures.

Closure innovation is not for Roulot, but he was among the first to recognize the benefits of judicious foulage, the practice of crushing the grapes. Crushing was historically used to cram as many grapes as possible into the press—something still practiced by less quality-conscious growers, usually followed by a rigorous press to extract as much juice as possible, since it is typical in Burgundy to sell white grapes in the form of must. Roulot, on the other hand, uses a light crush to allow a gentler press, thereby extracting about 75 percent of the juice at just 0.2 bar—essentially free-run juice released by breaking the skin at the crush. The following 15 percent of juice is extracted by pressing to 0.9 bar, and the final 10 percent at 1.6 bar. “If you don’t crush, that last part would be 40 percent,” he says.

Using foulage, Roulot finds the juice is finer, fresher, and requires minimum settling, though he takes the wise precaution of fully oxidizing that final 10 percent of juice to allow the unstable phenolics to precipitate. It is worth remarking that Roulot does push the end of the press, conscious of the role of “good” phenolics in the aging process, and agrees with the general consensus that the equipment and techniques used during the ’70s—the rougher Vaslin press, which extracted more solids, together with oxidative handing—probably made the wines of that era more stable. The pendulum has since swung too far in the other direction, with the widespread adoption of pneumatic presses and hyper-protective handling in the quest for fruit-driven wines. But these days, a generation of well-informed winemakers is intent on taking the useful aspects of more extreme approaches to find the best balance in their wine and the potential to age.

Simple and sublime

Roulot is rather solemn when discussing his wine—but asked about acting, his face lights up. Somehow, he managed to combine his role as wine producer with a secondary career as an actor. His latest role is a supporting one in The Taste of Things (La Passion de Dodin Bouffant), which he describes as a film about food, starring Juliet Binoche. Roulot plays a forester who takes the lead characters to his hut in the woods to demonstrate roasting and eating ortolan, the delicacy François Mitterrand famously ate for his last supper. (The songbird has been protected in France since 1999.)

Back to the civilized cuisine at Noble Rot, which Andrew struggles to define in simple terms. The chefs at the three restaurants bring their individual touch, but the general feel is Anglo-French. Soho chef Alex Jackson takes “a Provençal approach, with some Catalan and Italian influences,” says Andrew, while head chef Steven Harrison steers a Noble Rot focus on ingredients, allowing the ingredients to express their sense of place, a sentiment in tune with the terroir-focused wine list.

For the Roulot dinner, the simple first course was a very obliging dish that could happily have accompanied any of the vintages: meaty eel imbued with a whisper of smoke, perched atop a dense platform of soda bread, with light acidity provided by a dollop of crème fraîche and straws of green apple. It grounded the exuberant immaturity of the 2017, but I think it would have been best served with the 2007, providing support for this balletic wine to glissade-jeté across the palate.

The 2007 and 2008 vintages were accompanied by the main course of roast veal with bacon, morels, and slightly mushy peas; tasty, particularly the lamb sweetbreads flavored with chervil. It rather missed the mark with the 2007 but was very satisfactory with the savory 2008 vintage.

Jackson really hit the nail on the head with the dish for the 2009: perfectly poached brill in a generous puddle of sauce—buttery gorgeousness perfumed with wild garlic—which came together with the rich but elegant 2009 in perfect harmony. Simple and sublime. “I wish I could say we sat around tasting the wines and thinking up dishes,” said Andrew, “but I’d be lying.”

As an excellent wedge of Gruyère cheese landed on the table, Roulot announced that he had another little surprise. The Roulot family have been distillers in Burgundy since the 19th century, and perhaps making spirits is more fun than the serious business of producing wine, for there was a leavening of mood. That’s not to say that Roulot doesn’t take a meticulous approach to both processes, which at the press are linked. Not only does the gentle press cycle produce a fine juice, it has equal importance for the quality of the pomace from which the spirit is made.

In 2018, Roulot kept the pomace from five climats to distill a range of terroir-led marc; in acknowledgment, perhaps, of his father’s legacy. We tried the Tessons marc, of course. “The brandy is like the wine,” Roulot remarks; “Tessons has a bit more flesh than Luchets.”

The detritus of glassware cluttered the table: “Never knowingly underpoured at Noble Rot,” said Andrew. Downstairs I collected an umbrella that, on later inspection, proved not to be mine, for no brolly was needed as I stepped back out into Soho. The April shower had passed, and I walked home very happily through London’s glistening streets.

Tasting Jean-Marc Roulot Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir

Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir

Tessons is a sleek, intense, and feline wine. In my book, it can be equaled by a very good Narvaux, which will show more obvious minerality in youth and muscular grip. Tessons, however, is more consistent—both in the terroir and in the quality and style of the wine. Roulot describes it as a synthesis of Tillets and Meix-Chavaux. “If you draw a diagonal line between the two, it would go through Tessons.” To flesh this out, I’d add that Les Tillets, which lies at the top of the slope, produces slim, delicate wine with floral notes, while lower-sited Les Meix-Chavaux is fulsome, with more generous fruit. Tessons brings together the finesse of the former and body of the latter. We tasted from magnum, with the exception of the 1996.

2017 Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir

I love this wine, which canters excitedly across the palate. It grabs attention with its lemon-sherbet fruit and vivacity. It has crisp edges and a fine, powdery, talcy texture. Plenty of intensity, but with shimmering translucency. Pure and energetic, soft-salt finish.

2013 Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir

Slim-bodied, with lightly leafy notes. Not a lot of stuffing and a little looser than others in the lineup. Attractive, soft butter-mint notes on the palate and a gentle finish.

2011 Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir

With summer in spring and spring in summer, this season started and finished early, and the wine from this vintage found a point of balance in modest alcohol, acidity, and intensity. Roulot’s 2011 Tessons is typical in appearing more like a cool vintage than a warm and early one. Like many, it has aged better than initially expected. The 2011s are lovely now, and this Tessons is pleasing, light-bodied, trim, and slimly textured. Just nicely fresh and silky. “There was no excess of rain or frost in 2011,” recalls Roulot. “I don’t know why 2011 does not have a higher reputation. I prefer it to my 2010, which had botrytis. 2011 is a great vintage.”

2009 Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir

There is a sumptuous aroma but no heaviness to this 2009, which is lightly creamy, gently rounded, and elegant. The fine and firm core carries through to a pure and persistent finish. An excellent 2009.

2008 Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir

In the 2008 season, concentration in the wine was achieved through dehydration, thanks to a persistent wind before harvest. There was always some uncertainty about how this high-acid vintage—with total acidity higher than in 2007—would mature. Tessons has a drier, more savory profile than the fruitier, more youthful and energetic 2007. It is straight and salty, with a miso finish. I am not sure it will gain much from further aging.

2007 Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir

Pure, vivid, and well defined. The edges are precise. It is lively and crisp, with a delightfully stretched and lucid finish. Fresher than 2008 and richer than 2011. I love the tension. Top notch.

2004 Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir

Quite light-bodied and delicate, with a faint shimmer of minerality. It is not as persistent or intense as the surrounding vintages. Quite fragile. I feel the optimum moment has passed. Drink up if you have 2004.

1996 Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir

Cool nights at the end of the season maintained the high acidity, while the alcohol is a generous 13.5%. That firm acidity of ’96 can still feel severe in the reds, but the whites have benefited. This is fresh and sea-breezy. Of course, it’s a mature wine, maybe best appreciated for its aroma, but it has vigor and intention.

1988 Meursault Premier Cru Les Perrières

A butter-mint and dried-flower bouquet, with a hint of savory Marmite. There are toasted nuts on the trim palate, which glides smooth and silky. It is a fully mature wine and seems a touch oxidative in the middle, but it rallies on the finish, which is fresh, fine, and saline.