Anne Krebiehl MW meets Christian and Valérie Beyer, the modest but talented 14th-generation custodians of Domaine Emile Beyer.

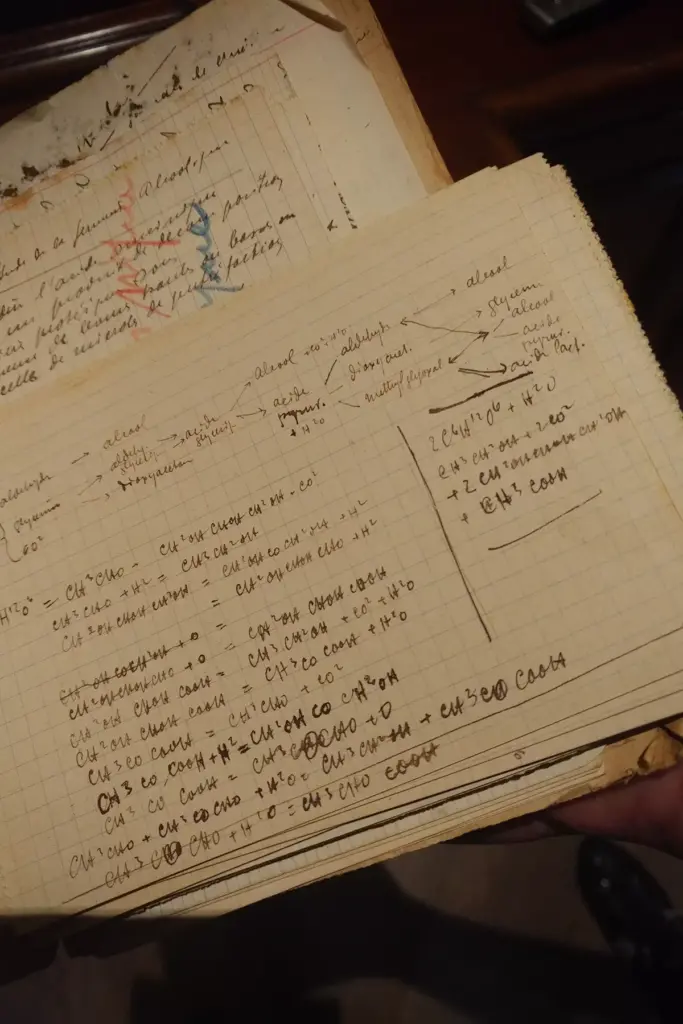

The writing is tiny, smooth, and cursive. Everything comes with a neat heading: Morphologie et biologie de la levure; le moût; les maladies de la vigne… Chemical formulae are listed under etudes de la fermentation, and there are notes on temperatures, enzymes, and the selection of yeasts (see photo, next spread). The flowing script, black ink on by now yellowing paper, evidently belonged to a practiced hand, someone used to writing, to studying; someone methodical and organized—in short, a scholar. That scholar was Emile-Victor Beyer, his pocket-sized notes distilling the teachings of the University of Dijon from which he graduated in 1928. Today, Emile-Victor’s inquisitive and diligent spirit lives on in Christian and Valérie Beyer. They took over the running of the family’s estate, Domaine Emile Beyer in Alsace, in 2004. “Our family is one of the oldest in Eguisheim,” Christian says. “We have lots of documentation, tons of papers, lots of it in German, lots in French. Even as children, we were aware that we would represent the 14th generation, and now it is our turn—and it is fun. It is a great responsibility, too, but I really like that my father said to me relatively early, ‘Now you are responsible, do your own things, carry on, do it well.’”

Having had time to implement his own ideas, it appears that Christian is guided more by the spirit of his grandfather Emile-Victor, whom he never knew, than that of his father Luc. Looking at Emile-Victor’s neat notes, which at the time represented the cutting edge of wine science, Christian says, “My grandfather Emile was an oenologue, with a diploma from Dijon. He wrote a lot; he knew winemaking, and at that time that was exceptional for two reasons: he could understand what was happening in the cellar, and he could speak French.” Alsace had become French again only in 1918, after a 47-year stretch as part of Germany, which had gained Alsace in 1871.1 That meant a wholesale switch in language, law, regulations, and, crucially, markets for the Alsace wine industry. Speaking French had thus enabled the young Alsace winemaker to study in Dijon while also working as a trainee at Patriarche in Beaune. “Er war fleissig,” Christian says in German (meaning that Emile-Victor was diligent and hardworking), switching as effortlessly from French to German and to English as his own grandfather, who had been one of the few villagers in Eguisheim who could speak English to the American soldiers who liberated Alsace in 1945.

Domaine Emile Beyer’s ancient roots

The beginnings of the family’s estate date back to the ownership changes provoked by the French Revolution. Formerly aristocratic or ecclesiastical estates then owned by the French First Republic were sold off as biens nationaux in 1792, and a distant forebear, Lucas Beyer, was able to buy the land in Eguisheim. His family had been local since at least 1580. “The plots my ancestor bought had belonged to the Abbey of Marbach,” Christian explains. “We can compare Marbach to Cluny, in that it was such a powerful abbey in terms of culture, wealth, and wine; it had vineyards all over the area,” Christian says. Founded in 1089 in Voegtlinshoffen, the Augustinian abbey, powerful throughout the Middle Ages, had once been the largest in Alsace. Its influence waned with the damages sustained during the ongoing conflicts of the 16th and 17th centuries, and it was dissolved after the French Revolution, when its lands were sold off. But Eguisheim, just a few miles south of Colmar, can look back on a much longer history: Cro-Magnon remains were found at Eguisheim, and the village is seen as the cradle of local viticulture, since the Celts made wine even before the Romans arrived.2 Christian explains that Eguisheim grew out of a very old settlement at a strategic crossroads: “It was a crossing of the Bergstrasse,” of the mountain route at the foot of the Vosges that avoided the soggy plains, coming from Breisach across the Rhine. The vineyards are ancient, and wine is deeply ingrained in Alsace culture, made rich and unique by its dual cultural heritage. The Beyer family prospered, and just 45 years after first owning vineyards, they were able to buy the former inn Au Cheval Blanc, right in the center of Eguisheim where the Beyers still live today.

The threshold of the magnificent house, hewn from local stone, is covered with the freshly fallen pink geranium petals from their last flush of flowering in late September. Eguisheim is one of those picture-book villages of medieval houses and cobbled streets, attracting thousands of visitors each year. The surrounding vineyards, however, are far less frequented and seem a world away from the touristy village. Standing in the Pfersigberg Grand Cru, where birdsong creates a constant soundtrack, Valérie and Christian point out three castles toward the Vosges in the west: Vaudémont or Weckmund, Wahlenbourg, and Dagsbourg. The Pfersigberg lies in a lateral valley, facing mostly south and southeast. Pfersigberg literally means “peach mountain,” and as poetic as that sounds, Christian explains that its likely etymology has more to do with einpferchen, to enclose, than with peaches. “But the name Pfersigberg was already in use in the 13th century, when all of Eguisheim and its surrounds belonged to the Bishop of Strasbourg,” under whose auspices Marbach Abbey fell.

As we walk, we can see the soil color change from the creamy beige of limestone, to a reddish tint. “There is a fault line here,” Valérie explains, referring to one of the fissures created by the Upper Rhine Rift 30 million years ago, which created not only the twin mountain ranges of Vosges and Black Forest on either side of the Rhine River but also the patchwork of bedrock that you find across Alsace, by pushing various geological formations of different ages to the surface. “On this side, we are on Triassic soils; the other side, by the chapel, is Jurassic,” Christian adds. “The Triassic soils are a mix of limestone and sandstone, with a bit of older granite mixed in, while the other side is pure Jurassic limestone.” Right now, we are in front of the 2.5ha (6-acre) Clos Lucas Beyer, named for the founder of the domaine, which lies within the Pfersigberg. Christian and Valérie also have another 1.5ha (3.7 acres) of vines within this grand cru. Clos Lucas Beyer was planted in 2010, and it is in these new plantings that the couple show their thinking. Nearly 1.5ha (3.7 acres) in the lower part of the vineyard were planted with 12 different massal Riesling selections at a density of 8,000 vines/ha on low-vigor rootstocks. All of them are from either the Colmar area or their own vineyards and bring loose bunches of Riesling with tiny berries. The upper part of the vineyard, just 1ha (2.47 acres), is planted to ten different Pinot Noir selections. Those from Alsace stem from 50- to 60-year-old vineyards, and those from Burgundy include the ATVB’s fin and très fin selections (see WFW 67, pp.22–26). For now, Clos Lucas is not yet bottled separately, because the Beyers believe that the vines are still too young, but they have set a clear course. Throughout the vineyards, individual vines are marked—these are the ones that might eventually make it into a massal selection. Christian speaks about preserving the genetic diversity of Riesling, Pinot Gris, and Pinot Noir and actively collaborates with a local nursery, Pépinières Hebinger, which has devised a new, gentle “F2” graft that does minimal damage to the graft union and thus improves sap-flow. The nursery even provides biodynamically grown rootstock.

Deep conviction

The Beyers began to convert their vineyards to organic farming in 2005/06 but did not become certified until 2014. In 2016 they started conversion to biodynamics and received Demeter certification in 2020. There is much evidence of this approach, which is clearly more than skin deep: fruit trees, like plum and peach, are dotted around, Christian noting that “every year we plant ten or 12 trees, where they fit into the landscape and do not impede work or cast shade.” Rare hoopoes nest in the vineyards, while lizards enjoy deliberately heaped stone mounds as their habitat. Later, in the Eichberg, our presence makes a hare leap and take cover in the vines. Cereals are sown between the rows to loosen the soil, Christian noting, “I don’t want to see naked earth.” A little rain brings out hundreds of snails, while potentilla sprouts between the cracks of drystone walls. “Building drystone walls has the same effect on me as yoga,” says Christian. “You really relax. You take a stone, and sometimes you take up the same stone ten times until you have found the right spot for it. It is very relaxing.” Fragrant cotton lavender, lavender, and rosemary are planted on the slopes, and Valérie says they deliberately created this Mediterranean ambience: “If you take a picture here in summer, you’d never think you’re in Alsace, but in Provence.” Christian believes he can find some of these herb aromas in the wine. Even more unusually, irises are planted everywhere. Why? “Because I love them,” Christian smiles. “Other people put ornamental plants in their offices, but this is where I work every day.” The vineyards appear less like farmland and much more like a garden.

While much of our talk revolves around Riesling and Pinot Noir, the Pfersigberg was and still is famous for Gewurztraminer. “We enjoy all our Alsace grapes,” Christian says, “but today Gewurztraminer is more difficult to sell than it was 20 years ago. The mood is not great for Gewurztraminer; today’s market is for dry, fresh wines.” This goes against this heady, full-bodied variety, which also seems to struggle more than other varieties with climate change; it accumulates sugar very quickly, and rapidly loses its already lowish acidity, so that balance is hard to achieve. Valérie says, “When we spontaneously open a bottle, we open Riesling, Crémant, or a Chardonnay grown on limestone,” confirming current drinking trends, then adds wistfully, “But when Gewurztraminers are 40 years old, they are completely wonderful. They are wonderful wines. We ourselves will not go for a young Gewurztraminer, which has more sweetness, more body, but when the wines are old, they are great. This is really tricky for us; the current market is difficult for these wines, but they have great potential.” Thus the couple are hesitant to give up on the tricky variety. “We have to take care of Gewurztraminer—we cannot just cast it aside,” Christian says. But the Beyers are also aware of Alsace’s positioning; a handful of leading estates are producing authentic and truly world-class wines, but so much of the production remains ordinary.

All of the Beyer’s vineyards are trained with a flat cane on the wire to curb yields, but you see just as many vineyards where the canes are trained in an arch to make space for more buds. “We are actually at a crossroads,” Christian says. “The next ten years, maybe five, will be so important, because of the choices we will have to make in the region. Our job is to find the best relationship between the soils and the grapes, and to put Alsace on the map again. This is our wealth, our roots, our culture, our identity—and it’s great, I feel good about that.” Just like his grandfather, Christian studied in Burgundy. He is a Beaune graduate and worked for Domaine Chanson. He also worked at Château Rieussec and at Schloss Johannisberg in the Rheingau, prompting him to say about Alsace, “We are in the middle—Burgundy lies to the south, the Rheingau to the north. I think we in Alsace are a bridge between these two cultures. We speak both languages, and I think I understand both sides of the Rhine. The French often see us at the top right-hand corner of their map, a little lost. But in the United States I saw a map of all the European vineyards, and the picture was completely different. We were right in the middle, not just that little lost French corner on the Rhine. We are in the center of Europe, and we can be proud of that.”

Meticulous viticulture

We walk a little farther and come toward the Sundel parcel within the Pfersigberg, deeper into the lateral valley and fully south-facing. “Sundel is the name that was given to the plot in the 17th century,” Valérie says. “It means ‘little sun’ in the Alsace dialect, but the original name Sodelin, used in the 13th century, could be translated into petite côte rôtie—it is the sunniest spot in Eguisheim.” Christian adds, “This is a plot my father bought in the 1960s, and everybody laughed at him because everybody knows that these vineyards do not produce a lot. This is why people used to call it ‘Idiotenberg’—Idiot’s Mountain—because the yields here are not high.” The topsoil is thin and lies over Jurassic limestone, yielding on average only 30–35hl/ha. All of Sundel, with its slightly red-tinged soil, is planted to Pinot Noir.

The young Pinot Noir vines are not trimmed; instead, their shoots are wound around the top wire of the trellis. This, says Christian, reduces the number of lateral shoots. “That’s the same for all vines, but for Riesling the handling is different.” Understanding the calibration between evapotranspiration, photosynthesis, and disrupting the hormonal signaling in the shoots—aligned to each year’s growing conditions—is at the heart of Christian’s vineyard work. “It’s very trendy not to trim leaves, but the more leaves you have, the more water you need, the vines have to pump more, and more leaves make grapes riper. So, we trim Riesling only once, as late as possible, after July 14, and it looks wild until then.” Walking past others’ plots, with the grapes only a few weeks from harvest, makes it easy to spot the different philosophies; the pure clonal selections are pristine, juicy, almost biblical bunches of plump berries—and they do look the part—but the straggly, loose bunches of Riesling, with their tiny, speckled berries, will make the better wine.

The Beyers have approximately 80 plots in and around Eguisheim, across 17ha (42 acres), with one third each of holdings in the grands crus Pfersigberg and Eichberg. “We really work with Eguisheim terroir and climate,” Christian says. Besides the Clos Lucas Beyer and Sundel within the Pfersigberg, they also have the cooler, elevated lieu-dit Hochrain above the Pfersigberg, and the lieu-dit of St-Jacques within the Eichberg Grand Cru, of marl and sandstone.

Gorgeous wines

Back in their light-flooded tasting room, its modern design skillfully blended into the half-timbered structure of the ancient building, we taste some of the wines together. The documents and mementoes in the display cabinet, however, are too diverting to focus straightaway on what is in our glasses. This is where Emile-Victor Beyer’s handwritten notes are kept, alongside old contracts, menus, family photographs, wine bottles, shards of tartrate from old barrels, an old hydrometer, and secateurs. “It’s a small personal museum,” Christian says. Old pamphlets, wine labels, and books again show that unique Alsace mix of French and German. A 1964 bottle of Pfersigberg Riesling has pride of place, since it shows one of the first labels created for the domaine by Colmar artist Robert Gall (1904–74). “The artist was a friend of Emile-Victor,” Valérie explains. “He asked him to draw the label, so Gall went upstairs to the second floor, opened the window, and drew what he saw: the castle, the church and steeple within the castle walls, a stork’s nest, and the three castle ruins in the distance, while the front is adorned with the three emblems of Eguisheim: the two keys as the symbol of Eguisheim, the white horse because of the former hostellerie Cheval Blanc, and St Peter, who is the patron saint of the church.” A smaller version of the same image still appears on the label. The wine is no longer made in the vaulted cellars. In 2009, life was made much easier with a purpose-built winery and cellar outside the ancient village and its narrow passageways. It is a functional space about to be expanded to accommodate more Pinot Noir.

Valérie’s and Christian’s wines are elegant and stand out for their nuance and dryness. Even the varietal wines at the entry level bear this out. In Alsace, where so much of the Pinot Blanc is banal, theirs showcases beautiful fruit. “Pinot Blanc is a great playground for clean, dry white,” says Christian, who does everything to preserve the subtle personality of this grape: immediate pressing, slow settling followed by spontaneous ferment in stainless steel, and maturation on lees until bottling in spring. The Pinot Gris, too, is always dry—which has become a rarity in Alsace and a challenge in increasingly warm vintages. That is why Pinot Gris has a slow press cycle of eight hours, affording it some slight extraction to help balance the wine. To add some mellowness in the face of the dry style, it is allowed to go through malolactic fermentation.

We spend a lot of time on the Riesling, which beguiles with its aromas. Christian speaks of his own evolution: “I don’t make the same wine I did 20 years ago; you are more skilled, you have more experience, but you also ask yourself more questions.” He notes that his massal-selected Riesling achieves phenolic ripeness earlier, “so you can express a clean freshness. I think I can express the lieu with ripeness, but with overripe grapes you can express only overripeness.” All the Riesling is hand-harvested into small boxes and whole-bunch pressed in a six-hour cycle. The juice settles naturally for between 12 and 24 hours, then ferments spontaneously in stainless steel. Depending on the year, malolactic fermentation may occur and is allowed to go ahead. “I am a great fan of stainless steel,” Christian says, “especially with my style of long lees aging. I like the freshness and clarity.” As we taste through vintages of the Domaine Emile Beyer St-Jacques Riesling—the heady and ethereal 2017; the creamy and shy 2016; the electric but balm-like 2014—and then the Domaine Emile Beyer Pfersigberg Riesling—2017 taut, ripe but slender; 2016 fragrant with that ethereal cotton-lavender tone; 2014 like a citrus elixir of gorgeousness; 2010 luminous and taut—the distinct personalities of the sites shine through: St-Jacques is like a firm handshake, Pfersigberg like a caress. “We go for dry,” Christian says about his resolutely bone-dry Rieslings. “Pfersigberg needs to be as dry as possible, or else the balance is not respected.” Each year is distinct, but from about six years of maturity onward, the limestone coolness and texture of Pfersigberg really comes through. But what is also evident is that the wines have become gradually more precise. “To taste Pfersigberg you need a different processor in your brain,” Christian says. “Pfersigberg is all about finesse, about calcaire bajocien; Pfersigberg is not demonstrative, it is delicate.” Christian refers, of course, to the Bajocian limestone of the Middle Jurassic, which is so close to the surface of the grand cru.

The Rieslings from the Eichberg Grand Cru are different again. The richer marl somehow buffers everything—in the vineyard and in the wine. “This plot never suffers from anything,” Valérie says. “No matter if it’s wet or dry, it is always constant.” Indeed, the wines seem creamier, mellower; even the super-bright 2010, with its killer acid, has its own kind of emollience, aligned to power and generosity. But of course we also taste a maturing Gewurztraminer from the cooling limestones of Pfersigberg. The vintage is 2011, the alcohol reaches 13.2%, with a residual sweetness of 50g/l and total acidity between 4.5 and 5g/l. Its aromas and textures are reminiscent of peach skin and garrigue, with something utterly seductive beginning to stir. “It is fascinating to see this wine evolve toward balance,” says Christian. So, yes, these wines need time. We don’t dive deeply into the Pinot Noirs, but the message here is clear, too: “If you have overripe fruit, you lose part of the story,” Christian says.

Valérie and Christian know exactly where they want to go with their wines. They tend their vines and vineyards with gentle gardeners’ hands, move with the seasons, and every year there is a touch more finesse. Both are curious about the world’s wines, and look both to Alsace and beyond for inspiration. Because there is so much to say and explore about Riesling, we don’t even talk about their Crémant d’Alsace. Their top cuvée is based on Pinot Noir and Chardonnay grown on limestone, aged on lees for five years, and disgorged without dosage. It is grown-up, complex, and savory; it has no need of sweetening, since it shows off the generous sunshine of Alsace, as well as the care and talent with which it is made. A central shaft of brilliant, bright freshness reveals it all. Of course there is only one person after whom it could have been named: the scholarly, exacting, diligent, and inquisitive grandfather: Cuvée Emile Victor.

Notes

1 The Prussian victory over France in the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War led to the foundation of the Deutsches Reich into which Alsace was incorporated. Ever since Europe emerged from the Dark Ages, through the Merovingian and Carolingian eras, Alsace had been a feudal territory of aristocratic and ecclesiastical estates in the collection of statelets (electorates, duchies, kingdoms, free imperial cities…) that became known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Under Louis XIV, Alsace became French from 1648 onward, until it became German again in 1871.

2 Homo Egisheimiensis remains can still be seen in the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar.

This article was first published in December 2020 in issue 70 of the print edition of The World of Fine Wine.