In a vintage One Bottle column first published in WFW32 in 2011, Andrew Jefford succumbs to the sensuality of Zind-Humbrecht 2008 Gewurztraminer Herrenweg de Turckheim Vieilles Vignes.

I seldom feel like Lord Alfred Douglas. This is perhaps just as well, given that the most celebrated of Oscar Wilde’s lovers had a life rendered miserable by self-indulgence, given that he was long estranged from a vengeful and violent father, given that he was an anti-Semite who squandered much of his inheritance in libel actions (both as plaintiff and defendant), and given that the mental illness that ran in his family—one prone to a disproportionate number of “shooting accidents”—was eventually to claim his only son. He was, though, also a poet, and his 1894 poem “Two Loves,” which played a crucial part in earning Wilde his “gross indecency” conviction and two years’ hard labor in Pentonville, Wandsworth, and Reading jails, concludes with the celebrated line, “‘I am the love that dare not speak its name.’”

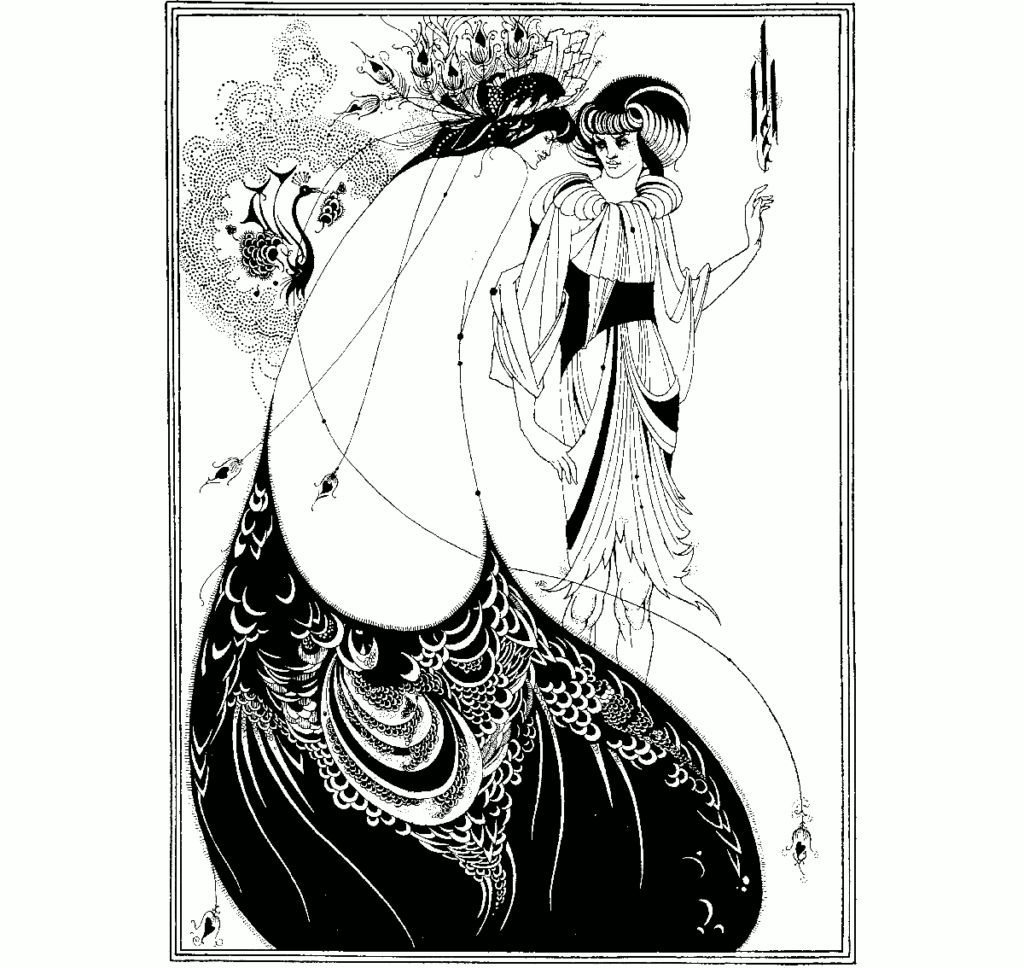

This is when those of us who love Gewurztraminer begin to empathize with Bosie. In right-thinking wine drinking circles, there is something a little shameful about admitting that you regularly spend an evening with this lilac-berried mutant and even enjoy the experience. The “first love,” the sort that fills “‘The hearts of boy and girl with mutual flame,’” would of course be a passion for respectable Riesling—upright, straight as a poplar, its pencil stiffened with acidity, and usually properly dry or properly sweet without too much hanky-panky in the middle. Riesling and rectitude are bedfellows (in wedlock, of course). Whereas Gewurztraminer is doubtful, languid, and fin de siècle—at best a Rosenkavalier and at worst a Salome, with its head-slicing alcohol levels, its neglect of acidity, its copious flesh, its chaotically unpredictable levels of residual sugar, and its uninhibited perfumes, oscillating between rose garden and bedroom, and occasionally growing more meaty and truffley still until it suggests an uninhibited aromatic account of a full-body massage and beyond. But there you are: I love it. What can you do? There’s no point in denying your own nature.

I don’t have a lot of patience with the customary criticisms of the variety, unless they originate from unfortunates who have never tasted a good one. (Bad Gewurztraminer, it’s true, is one of the most horrible of all wines: pharmaceutical, mawkish, oppressive.) The notion that there might be some set of universal aesthetic parameters to which all white wines should conform is suspect, suggesting industry rather than agriculture and implying a homogeneity of taste that the diversity of the world’s great cuisines effectively demolishes. Indeed, I would defend Gewurztraminer (even if I didn’t like it so much) on the basis of its magnificent gender-bending efforts and the fact that it can find a resonant balance down in the lower depths where acidity has almost disappeared and where extract and tannin begin to drag agreeably on luscious, glycerous fruits. Perfume is always there to lift the wine, no matter how low it has sunk; that’s what helps itsurvey the stars from the gutter. Any universal judgment about sugar levels is misguided, too. Gewurztraminer can be a fine dry wine and a fine sweet one, too, but it’s most compelling of all in the middle. That is where you feast with panthers; the combination of scent-saturated sugars with the other components in a densely knitted wine seems to give it a provocative unpredictability of allusion. The danger may indeed be half the excitement. Those who insist on dry wines alone at table are living on a restricted diet.

The notion that Gewurztraminer is an egotist capable only of shouting its own varietal nature at the expense ofterroir doesn’t bear scrutiny. Try a Gewurztraminer from Schlossberg or Brand, then compare it with one from Sporen or Goldert. Taste them all blind. Involve the family: Ask them to be served to you when you least expect it. The granite and mica of Brand may begin to throw you off the scent, though it remains warm enough for exoticism; Gewurztraminer from the silicious scree of Schlossberg, though, can seem like a different variety. The archetype in Alsace implies clayey marl, a long season, and a speckling of hot days and cooler days. That heady Sporen or Goldert profile is what ignites seduction.

This wine, in fact, is grown off the hill on gravels mixed with loam, and mineral complexity isn’t its foremosttrait. It comes, though, from 62-year old vines in biodynamic cultivation, low yields of 29hl/ha, and sumptuousripeness (with about 20 percent botrytized fruit). It’s been vinified with the intelligence, care, and patience typical of Olivier Humbrecht MW. The result is not individuated in the way that a grand cru might be—but for sheer completeness, extravagance, and exuberance, this yellow wine is regal. Aromas ooze from it like lava from a volcano: honey, ginger, jasmine, lemon, pineapple, white chocolate, crushed roses, bramble fruits, baked apple with brown sugar… Its 76g of sugar per liter is carried almost pertly, thanks to a TA of around 7.8g/l in tartaric (5.1g/l in H2SO4), saturated with fruit flavors as only the acidity of a season in the field can be; the 14.3% of alcohol wrapped up in all those other things gives it lovely glide on the tongue. There’s something fiery in its heart, meaty in its depths, chewy in its texture. And carnal in its nature. I challenge anyone to sip and then walk away. It would be unnatural, even perverse…