Alex Maltman explains how five of the world’s most celebrated vineyard soils earned their exalted reputations.

When young William Gimblett sailed out of London in 1878, headed for a new life in New Zealand, he must have had little idea of what lay ahead of him. He is scarcely likely to have imagined that 30 years later he would be raising sheep, acclaimed for his precocious “Gimblett lambs.” That came about because, after settling in the North Island’s Hawke’s Bay, he purchased some land just inland from Napier, strikingly stony but nicely sheltered, and its relative warmth meant his lambs reached maturity considerably earlier than those of his neighbors. And he is extremely unlikely to have imagined that, 100 years later, the land would be bearing grapevines, with those self-same, warm, gravelly soils given his name and known to wine enthusiasts the world over.

All the world’s grapevines are, of course, growing in soils of one kind or another. They all provide stable anchoring along with water and nutrients; but in just a few places, they have acquired a designation of their own, names that are treasured by wine lovers. So, we have galestro and llicorella, Willakenzie and gore, roten schiefer and galets roulées—names that probably mean little to most people but that, for wine enthusiasts, can prompt images of special places and wines of distinction. In this article, I will explore the stories and the science behind five such named soils, examples that have become legendary in the world of wine.

The Kimmeridgian of Chablis

Where is the largest onshore oilfield in western Europe? It’s in the southwestern UK, and is certainly no newfangled development. For centuries, the folks there knew that some of the local rocks could burn, and from them such things as varnish, grease, and paraffin could be manufactured; a “nodding donkey” outside one of the villages has been pumping oil for more than 60 years. The name of the village? Kimmeridge.

The word is legendary to wine lovers: the Kimmeridgian of Chablis is perhaps the single most famous vineyard soil in the world, and the best loved. Perhaps it is also the most misunderstood. Why so? Well to start with, my point in mentioning oilfields is to underline that in geology “Kimmeridgian” denotes a particular period of time and not a kind of rock or soil: There are no hydrocarbon-bearing strata around the village of Chablis. But the limestones and marls at Chablis formed at the same time as the oily rocks at Kimmeridge, so both are referred to as Kimmeridgian in age.

Similarly, there are rocks at Kirkland Lake, just west of the Quebec/Ontario province line in Canada, that formed deep within the Earth—so deep that they experienced pressures sufficient for diamonds to form in them. They are Kimmeridgian. In northern Turkey, there are Kimmeridgian granites; and very different kinds of igneous rock, though also Kimmeridgian, occur in the Coast Ranges of western California. In other words, describing the vineyard soils at Chablis as Kimmeridgian carries little meaning without prior knowledge of what kinds of materials they are.

But (putting aside the problem of explaining the popular belief that the particular nature of Chablis wines is somehow due, notwithstanding the unique climate and physical setting of the Chablis slopes, to the vineyard soil) there are also further misunderstandings about the term.

Wine writers seem to assume that in science the term Kimmeridgian is neatly defined; in fact, geologists have argued about exactly what it means for more than 200 years, sometimes decidedly vituperatively. Some have recommended that the term should be discarded altogether. Finally, however, as recently as 2021 an international scientific agreement was reached on what Kimmeridgian should actually mean. Even so, one continuing problem in practice is that the now-accepted definition is based on certain fossils (very particular kinds of ammonites) that aren’t present in many rocks probably of Kimmeridgian age, and this is the case at Chablis.

In any case, for us in the wine world there are two problems that are more fundamental than these technical matters. First, grapevines simply don’t care anyway, so to speak, about the geological age of the vineyard rocks. Wine promoters and commentators love to mention the names of geological periods and often imply that the older the age of the vineyard rocks, somehow the more profound and complex the wine. Really, however, it’s the physical and chemical properties that are relevant to the vine, not the geological age, no matter how old.

Second, all this business of geological age is referring to the bedrock, the intact substrate of the vineyard. It may have fissures into which deeper vine roots probe for supplementary water, but otherwise it is the overlying, humus-bearing, loose material—the soil—in which most of the vine roots grow and obtain water and nutrition. And almost invariably, the soil is vastly younger than the bedrock. In most of the world’s temperate zones, certainly in the glaciated northern hemisphere, the soils are no older than a few thousand years and are still forming. In other words, the phrase “Kimmeridgian soil” isn’t really referring to the soil at all.

The Kimmeridgian bedrock at Chablis lies beneath the middle parts of the vine-covered slopes, with younger strata capping the hills and older ones at the base. The soil, though, isn’t fixed; through time it inevitably creeps downslope. So, for centuries growers have had to cart the jumbled debris accumulated at the foot of the slopes back up to where the vines are growing; consequently the mid-slope viticultural soils are rather mixed.

A Google search linking Kimmeridgian and Chablis yields thousands of results, nearly all enthusing about the importance of the connection between the two. Few, though, suggest that there are any difficulties.

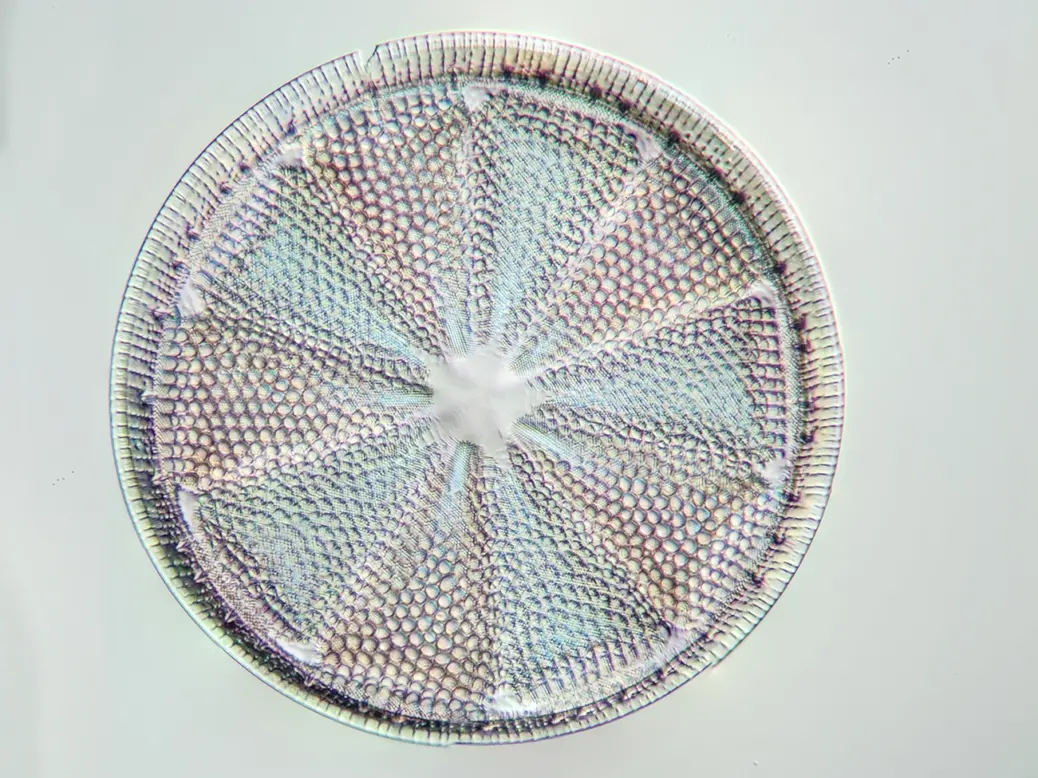

The albarizas of Sherry country

Diatoms and radiolaria (see previous page) have been called “architectural marvels.” The filigreed arrangement of their glassy white shells has inspired structures such as geodesic domes, as well as visionary furniture. Both kinds of creatures are extremely tiny—they’re varieties of microscopic oceanic plankton—and they are both made of silica (silicon and oxygen). There are other similarly intricate planktonic organisms such as foraminifera, but with shells made of white calcium carbonate. All of them float in the world’s oceans in prodigious numbers and sometimes, if conditions are right, one of the varieties can flourish in even more extraordinary numbers, the debris dominating the ocean-floor sediments.

Exactly that happened around 20 million years ago in the seaway that then connected the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. (The sea floor eventually became uplifted to make land, the region of Spain we know as Andalusia.) From time to time, sands or muds would sweep in from the nearby land, and although diatoms flourished throughout, populations of the other plankton fluctuated as conditions in the sea water varied. Today, all this has an influence on the drink we call Sherry.

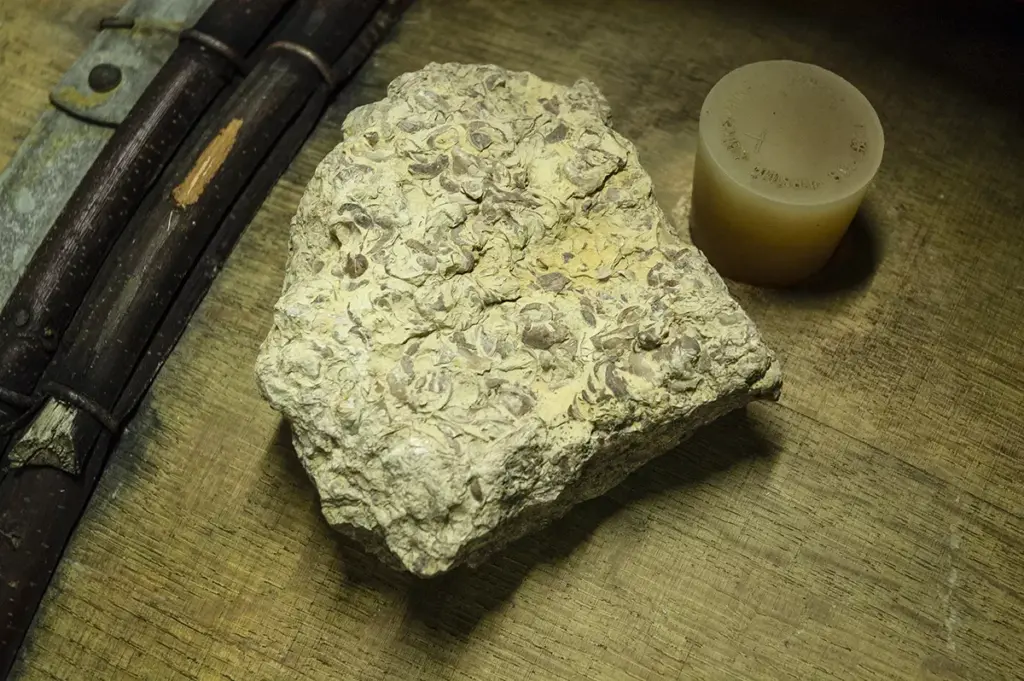

Back in time, a series of sediments was built up on the sea floor, eventually to be hardened into rocks with the planktonic organisms preserved as microfossils. Today, those rocks—essentially marls—form the Andalusian landscape and are weathering into soils. They are known there as moronitas and all are rich in diatoms. But in the Jerez-Sanlúcar Sherry district, they have vernacular names such as arenas for those that are sandier or barros for those richer in clay. And for those particularly rich in calcareous plankton—all pale colored but in places startlingly white—albarizas. These well-drained, low-fertility soils yield the finest grapes for Sherry, not least because they tend to occupy the tops of the area’s rolling hills and hence benefit crucially from cooling sea breezes.

Additionally, the fossilized hollow shells of the plankton, together with the little spaces between them, give the soils a loose structure that allows extensive root systems and an excellent capacity for storing rainwater—invaluable during the arid growing seasons of Andalusia. A piece of albariza, surprisingly light because of all the little holes, can absorb up to one third of its volume in water, rather like a sponge. (These white, powdery albarizas are often called chalk, though geologically speaking they contain insufficient amounts of the microfossil that defines true chalk—coccolithophores—and they formed about 70 million years after the type of chalk in England and northern France.)

With time, the region’s growers learned of subtypes of albariza soils and demarcated the different wines they yielded. During the past century, however, such nuances became lost as the market for Sherry dwindled and wine store shelves became dominated by heavily promoted brands. Wine distinctions deriving from their terroirs vanished.

Today, a new generation of producers is striving to restore the status of Sherry as a fine wine and to resuscitate the characteristics of different vineyards. The albarizas terroir scheme devised by García del Barrio Ambrosy, for instance, has seven different subclasses, based on such things as altitude or slope, as well as the soils. Right now, there are around 20 producers selling wines emphasizing their derivation from different types of albarizas. Examples include tosca de barajuelas, the soil richest in diatoms and hence the lightest and most porous, with a leafy, laminated structure that encourages the roots to grow sideways. Tosca cerada is more calcareous, with the lowest proportion of siliceous diatoms, soft when wet but becoming baked when dry. The soft, foraminifera-rich tosca lentejuelas (literally “sequins”) encourages deeper roots, which is said to give lighter, more elegant wines.

Almost certainly, the contribution of these soils to the differences in the wines arises primarily from fine variations in their water-holding capacities, due to various proportions and compactions of sand grains, clay, and the different microfossils. But there may be additional effects. Some growers say that the thicker grape skins produced on softer albarizas like barajuelas bear a lesser proportion of wild, indigenous yeasts and that the soils may even influence the kind of yeast. Some say that softer albariza soils encourage the vigorous beticus strain, whereas wines from denser soils have a higher chance of developing the gentler montuliensis. These are both film (surface) yeasts, and so are intrinsic to the flor that characterizes Sherry.

Perhaps, then, Sherry is on the threshold of a new terroir-driven era, with the albarizas regaining their celebrated status and familiarity. (The word is already appearing, through the Sherry casks used for aging, on the labels of some whiskies.) And central to it all, down there in the Andalusian soils, are those little architectural marvels.

Napa’s Rutherford dust

It’s a catchy phrase, Rutherford dust. Growers in California’s Napa Valley love to use it and, inter alia, it has appeared in poetry, as the trademark of a bottled water, and as the title of pieces of music. But in the wine world it’s of mythical status—and some would say literally so. For whether it actually refers to a soil is much debated; what the term really means is far from clear.

There seems to be no record of the expression’s origin; how and when it was first used is clothed in anecdote. Some say it’s due to the great UC Davis academic Maynard Amerine. That’s not hard to imagine, seeing as Amerine was so fond of sayings: “Wine quality is easier to detect than define”; “Drink wines, not labels”; “Wine is a chemical symphony”…

But most point to the much-quoted saying of André Tchelistcheff: “It takes Rutherford dust to make great Cabernet.” At face value, this seems a pretty clear reference to soil, but Tchelistcheff, being winemaker at Rutherford’s Beaulieu Vineyards, would have known very well that the soil there is a far cry from being dusty. Dust is fine stuff, carried by the air. The Rutherford AVA stretches eastward, from alluvial gravels across the valley of the Napa River, which over time has deposited spreads of loams, sands, and silts. Nothing as fine as dust, and none of it ever airborne.

The western parts of the AVA flank the Mayacamas Mountains and are slightly higher than the valley floor, a landform colloquially called in this part of the world a “bench.” The Rutherford Bench is home to such revered wineries as Inglenook (formerly Niebaum-Coppola Estate) and Far Niente, as well as Beaulieu, and consequently many a wine-loving tourist wants to see the celebrated bench. The relative elevation is only slight, however, and the slope onto it barely noticeable, say, as you drive on Highway 19. So, one or two institutions here have thoughtfully catered for sightseers by providing a fittingly named wooden bench, for sitting and taking selfies.

The real Rutherford Bench is an alluvial fan, formed by streams emerging from the Mayacamas Mountains and immediately dropping their coarsest sediment. Less coarse material is carried farther eastward, down to the middle parts of the apron. The finest sediment forms the outer fringes, where it interfingers with the alluvium of the Napa River itself. The soils are of suitably limited fertility and superbly drained—some vine roots probe 20ft (6m) or more to find their water. In reality, it’s all more complex than this, not least because through time the streams switch their routes and braid across the fan, which is why the soil properties vary so intricately.

Why, then, did Tchelistcheff (or whoever) refer to these coarse soils as dust? Certainly, some believe the term does refer to the soil: “Rutherford dust is a mixture of gravel, sand, loam, and volcanic deposits that permeates the Rutherford bench plateau [sic]”; “We walked between the vine rows, kicking up the famous Rutherford dust.” Perhaps Tchelistcheff really meant “dirt,” in the colloquial American sense?

More commonly, the expression is taken to refer not just to the soils but rather to the overall characteristics of the area: Rutherford dust “essentially refers to the unique terroir particularly with respect to Cabernet Sauvignon.” The Rutherford Bench experiences Napa’s warmth but is nicely tempered by maritime air drifting northward from San Francisco Bay; it receives relatively more sun exposure through being located at the Valley’s widest point yet has a significant diurnal temperature variation. These special combinations lead to wines of special character, and many believe that the true meaning of the phrase lies in the wine itself.

But even this is unclear. Some think of aroma: “an intriguing aromatic element often referred to as Rutherford dust”; “the signature Rutherford dust smell.” Whereas others think of taste: “a mysterious, spicy element known as Rutherford dust”; “the wines are very Rutherfordesque. You can taste the dust.” Mouthfeel, however, is most commonly mentioned: “a nuance attached to the back of the mouth”; “Tchelistcheff was talking about granular or ‘dusty’ tannins that couple with cocoa powder.” Tannins are frequently mentioned in tasting notes on Rutherford wines, and research has shown that a restricted water provision, exactly as these bench soils provide, is an important factor in developing grape tannins.

Given the experience and insight of people such as Amerine and Tchelistcheff, it seems likely that something like this was in mind when the term was coined. That’s the view of the association of local wineries, the Rutherford Dust Society: The word dust “evokes in four simple letters a specific place and a complex set of flavors.” As Andy Beckstoffer, who worked with Tchelistcheff, put it, “When he said, ‘The wines must have Rutherford dust in them,’ he did not mean they had to taste of dust. André meant they needed to taste like they came from Rutherford’s vineyards.”

Even so, there are those who see the phrase as purely allegorical, referring figuratively to a “magic dust” sprinkled over this charmed area. Or perhaps with a touch of cynicism, a “gold dust,” reflecting the dizzying prices that some of the area’s wines can command. (Tchelistcheff once said that “money is the dust of life.”)

Yes, Rutherford dust is a catchy phrase, but its meaning is imprecise, apparently lying somewhere in a blurry matrix of interpretations. Perhaps, to paraphrase the words of Humpty Dumpty—not unlike some other words in the wine lexicon—it means what you want it to mean.

The terra rossa of Coonawarra

Picture the scene: the Australian Outback. A vast horizon shimmering beneath an azure sky, bushy acacias and perhaps eucalyptus, maybe even a kangaroo or two. And, of course, the red ground. In places, dazzlingly red. Much of interior Australia has a distinctly ruddy look, and it’s essentially due to iron.

Warm regions across the world tend to have soils that are more or less red, depending on the proportions of certain iron minerals. Most widespread is the rust-orange, ocherous goethite, named after the German polymath and avid mineral collector. Hematite, as its name suggests, is the color of blood, and it’s this that makes some soils so vividly red. That effect is seen widely in Mediterranean areas, where the soil has long been venerated. Since ancient times, it has been used as a pigment in sacred tombs, and in certain religions it’s seen as the very dust from which God created man. (In Biblical Hebrew, the soil is called adamah, dam meaning blood and adam meaning red.)

In recent centuries, the reddest soils have become known by the Italian name terra rossa, and science has long been grappling with understanding them. Exactly how red do the soils have to be to justify the name? Hence, scientists juggle with the hues (specific colors), values (lightness and darkness), and chromas (color intensities) to try to agree on limits of appropriate redness.

How do they form? There is general agreement that true terra rossa forms only on limestone and usually involves the slow dissolving away of calcium carbonate to leave an insoluble residue of clays stained by hematite. But in some places, rather than being a residue, the limestone has been slowly replaced by iron and clays in situ, by capillary waters rising through the rock. And elsewhere, chemical analyses show a substantial input of red material that must have originated somewhere else, such as the wind-blown Sahara dust in the terra rossa of Croatia’s Istrian peninsula.

There’s also a consensus that terra rossa formation needs warm summers but wetter winters, plus well-aerated, oxygenized conditions so that the insoluble oxidized form of iron—ferric oxide, the mineral hematite—forms preferentially over hydrous goethite and other forms. Just such conditions arose in South Australia, in the region now called the Limestone Coast. And as in Mediterranean areas, the resulting terra rossa soils have proved conducive for growing quality grapes, such as in today’s noted wine regions of Robe, Mount Benson, Wrattonbully, and Padthaway. And of course Coonawarra.

Scotsman John Riddoch first succeeded with Coonawarra wine, such that by 1896 he was able to build a fine sandstone winery, with a distinctive triple-gabled frontage. For various reasons, however, his initial success gradually faded, though the locals remained convinced of the area’s brilliant potential. Eventually, after decades of neglect, in 1951 the Wynn family took the bold step of buying Riddoch’s old winery and its surrounding vineyards with a view to producing world-class wines. It worked. Just two years later, their Wynns Coonawarra Estate Claret was being exported to England—transported on the royal yacht Britannia, no less. Today, the Wynns label, with its triple-gabled insignia, is one of the wine world’s most iconic.

Nowadays, there is little of Coonawarra’s narrow strip of terra rossa that is not carpeted by thriving vineyards. Some of them produce grapes under contract; others supply the three dozen or so cellar doors. Several of the latter are so proud of their soils that they maintain a trench so visitors can clamber down to see how the vine roots probe through the red soil to try to penetrate the hard but fractured limestone below. Two things are immediately noticeable in the trench walls. One is the abruptness of the change from the terra rossa to the underlying white limestone. Second is the “waviness” of the line that separates the two, representing in three dimensions an irregular, uneven boundary, just the kind of surface that limestone forms when exposed to the atmosphere: the fissures and pits of karst.

Plenty of wine writings still refer to Coonawarra’s terra rossa being an in situ residue, but it’s more complicated than that. During the past half-million years or so, the Limestone Coast region consisted of a series of coastal reefs and dunes, changing position and height as sea levels fluctuated. Accumulations of wind-blown calcareous clayey silt, sitting on a porous limestone bedrock and filling its surface hollows, produced the higher ridges. The Coonawarra strip is just such a rise, merely meters higher than the surrounding damp land but sufficient to give a drainage and aeration that leaches the calcium from the wind-blown deposits to leave insoluble clays reddened by hematite.

Today, the resulting terra rossa provides a restrained fertility ideal for grapevines, together with some water storage, crucially enhanced by the underlying fissured limestone. Moreover, the rise in elevation, albeit slight, raises air dryness and exposure to sunlight. Consequently, the Cabernet grapes for which Coonawarra is noted are smaller and more intensely colored than those from the adjacent moist soils, and their phenols ripen well to give the area’s characteristic blackcurrant and minty wines. The wine color, incidentally, is largely due to anthocyanins, the red pigments in the grape skins, and despite what some writers assert, it has no connection with the redness of the soil.

Coonawarra is hardly a tourist mecca. It’s located away from the region’s main highways and is a strip of virtually flat vineyards with mostly new winery buildings; the settlement itself comprises little more than a shop, a restaurant, and a few cottages. Yet to watch its terra rossa glowing under the setting of a flaming Australian sun is a wondrous sight, worthy of one the world’s most famous vineyard soils.

The Gimblett Gravels of Hawke’s Bay

One hundred and fifty years ago, much of New Zealand’s North Island belonged to the Māori, but European settlers were arriving thick and fast, seeking to claim the most fertile tracts. The Hawke’s Bay area was attractive: Three major rivers were bringing in spreads of fertile alluvium, its climate was “proverbially mild and healthy,” and the Crown was negotiating the purchase of blocks of land. But there was a snag for the new settlers, especially farmers: the threat of flooding.

Māori lore told of devastation resulting from periods of intense rain and swollen rivers every 40 years or so. Thus it was in 1867, when in ten days more than 15in (38cm) of rain fell and the rivers broke their banks: “The whole country from the hills in the extreme distance to the town of Napier was one vast sheet of water.” When the floodwaters eventually subsided, the Ngaruroro River had changed its position and, within five years, had completely deserted its old course. The pebbles and boulders that once formed the riverbed were left high and dry.

This new, stony ground was of little interest to the established farmers, but some settlers tried to see if anything could be done with it. There were efforts at sheep farming, and so it was that William Gimblett—he of the introduction to this essay—purchased some land and tried his hand at it. But his initial success with early lambs was not to last; the barren shingle was simply unable to sustain grazing pasture year after year. He had to move on. He vacated the land, and the access track he had used was gated off, though still vaguely referred to as Gimblett’s.

That riverbed land seemed pretty useless. One writer remarked that even rabbits wouldn’t venture onto it without taking a packed lunch. In 1981, however, another emigrant Englishman saw a new possibility. Chris “CJ” Pask had a few vineyard plots in coastal Hawke’s Bay and ran an aerial fertilization business with his little Auster aircraft. His plots could produce decent Merlots, but the great prize of the time, Cabernet Sauvignons, were in most years too unripe and herbaceous. Cabernet was deemed “a difficult cultivar.”

One day, however, while flying over the dry pebbles of that old riverbed, CJ was reminded of the gravelly soils he had seen in the Médoc and wondered if his Cabernets would have a better chance of ripening on that shingle—with a bit of his aerial top dressing. The inland areas were a few degrees warmer than those near the coast, and new measurements were showing the soil temperatures to be warmer still. That looked promising.

Several other growers took notice and planted a few vines. And to some surprise, when the wines were ready, they attracted considerable acclaim; what followed is now the subject of textbooks and scholarly articles on wine marketing. The growers organized themselves into a formal association and, instead of the usual approach of seeking an official appellation or protected geographical identity (a device that had never been embraced much by New Zealand producers anyway), applied for a registered trademark. The group didn’t specify techniques or grape varieties but sought to “protect and develop the reputation of the area” by precisely defining its limits, laying down strict quality requirements for the wines, and, of course, inventing a brand name. The area’s striking character lay in its river gravels, centered on William Gimblett’s old track. So the brand name simply fell out: Gimblett Gravels.

The chief contribution of the gravelly soils is their free drainage. This results in a low soil fertility that restricts both the vine canopy and the sward between vine rows, enabling the bare stones to absorb the day’s heat for re-radiation at night. There is just enough topsoil to provide the humus-borne essential nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur, but all the other nutrients have to come from irrigation. Hawke’s Bay waters come largely from the inland mountains, rising among the deposits of the great Taupo volcano and passing eastward through a variety of sedimentary rocks such as the very impure sandstone called graywacke. Consequently, they easily have sufficient dissolved nutrients.

Food purists may scorn tomatoes, salad crops, and the like produced hydroponically, but that is essentially the way these premium grapes are being grown. Viticulture here is impossible without irrigation; vines begin to fail if rodents chew through the supply pipes. So, it’s an interesting observation that while wines from the Gimblett Gravels are often cited as examples—outstanding examples—of terroir-driven wines, the grapevines’ vital water and nutrient supply come from far away.

Today, the area’s Cabernets are of international stature, while other red grapes such as Syrah, Tempranillo, and Malbec are fast gaining in repute; competition for space within this restricted acreage is fierce. A couple of statistics sum up this explosive success of the Gimblett Gravels. In the early 1980s, one hectare (2.47 acres) of land here was changing hands for less than $10,000; in 2020, the rate was more than $150,000. Provided, that is, it was within the area entitled to the Gimblett name. William himself would surely be amazed.