Wine was a gift of the gods in most antique Mediterranean civilizations, says Stuart Walton. And for those of us willing to listen, these ancient myths still resonate today.

We do not have a pre-eminent archetypal myth for the origin of wine. Its status as a gift from one deity or other is common to most of the antique mythologies of the Mediterranean basin, reflecting the primordial beginnings of wine in the Middle East, perhaps present-day Iran or Syria.

Accounts of the route of transmission from the gods to humankind may be at variance with one another, but there are connections between these ancient stories that still speak to our experience of wine today, if we are prepared to let them.

Fill your belly with good things

The Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh is still the oldest extant written narrative in the world, originally incised on clay tablets in the early centuries of the third millennium BCE. It tells of the travels of the titular king, who goes out into the world to gain experience, in the manner of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister.

On the journey, Gilgamesh encounters Siduri, a wise and benevolent goddess who dwells in the land of the cultivated vine. The story stops short of claiming that it was she who taught winemaking to the mortals, but she does make an interesting attempt to dissuade the hero from pursuing the elusive goal of self-discovery:

“Where are you hurrying to? You will never find that life for which you are looking … fill your belly with good things; day and night, night and day, dance and be merry, feast and rejoice.” (trans. Nancy Sandars, 1960)

This is nothing less than “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,” more than four thousand years ahead of Robert Herrick. The primary duty of the wanderer is caring for his wife and child, and attending to his own hygiene, a regime within which drinking can take its customary place.

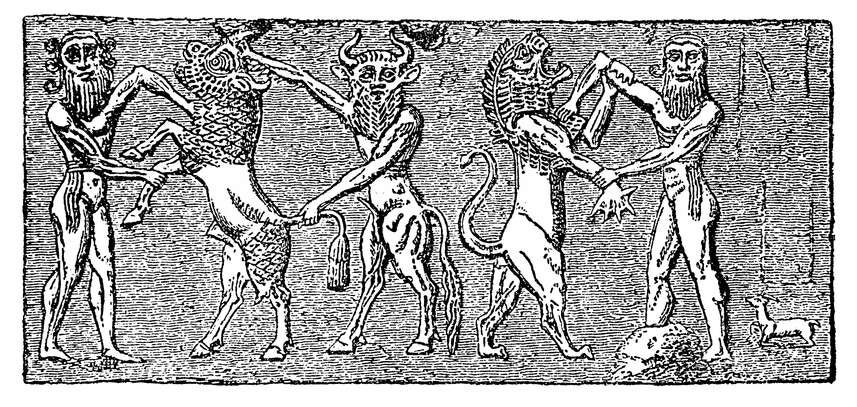

Wine is not, be it noted, the orgiastic sacrament that it will become in Greco-Roman myth, but precisely a civilizing agent. Enkidu, the hellraising nature boy of the epic who will become the boon companion of Gilgamesh, is transformed into somebody you might be happy to have in for a Sherry at Christmas, not by Siduri, however, but by Shamhat, a young worker in the temple of love who introduces him to wine:

“So he ate till he was full and drank strong wine, seven goblets. He became merry, his heart exulted and his face shone. He rubbed down the matted hair of his body and anointed himself with oil. Enkidu had become a man.”

Wine in Egyptian myth

In the simplest of Egyptian mythic beliefs, Osiris was the progenitor of viticulture who taught the art of winemaking to the people. Since he was also resurrected by his wife Isis, following his fratricidal killing by Seth, he is associated with rebirth and renewal, his symbol becoming the ever-renewing grapevine.

His blood was what reddened the floodwaters of the Nile, which in turn nourished the vines. The blood of Osiris turns this water into the wine that is then offered back to him in tribute, sacrifice and libation.

According to one of the earliest Dionysian myths, from the dark ages of Thessaly, Dionysus, a guest in the house of Eneo, imparts the secret of viticulture to his host as a gesture of gratitude for being allowed to sleep with his wife.

The obliging host’s name is then transmuted into the Greek word for wine, oinos. Dionysus, it should be recalled, was a late arrival in the Olympian pantheon, formerly an untamed savage from further east in the Thracian hills, which is why elements of riotous debauchery remain in the Dionysian festivals. Wine is at once the civilizing agricultural staple, from whose soil the efflorescence of culture itself will spring, but also, inextricably, the means by which we leave civilization momentarily behind when necessary.

Noah’s vineyard

In the Pentateuch, wine makes its first appearance in the story of Noah, who plants a vineyard to celebrate his family’s surviving the Flood. He is the first person in history to get drunk, in the course of which he disgraces himself before his sons.

Whether there was a Satanic influence in transforming the juice of the grapes into something dangerous has been widely debated in the rabbinical literature, but if Noah is the father of fermentation, he too has joined the cultural aspect of grape-growing to the metacultural experience of intoxication.

The wine the vineyards yield is the reward for the backbreaking labor of tending them, and so forth in an inexhaustible cycle that will make Noah’s nectar almost as essential to human thriving as Adam’s ale.

Continuities emerge diachronically from the deeps of antiquity: Wine is the lifeblood and refreshment of the gods. When red as life’s blood, it symbolized the sacrifices that were once made in real blood. It was one of the foundation-stones of agriculture in the Neolithic revolution. In fertility rituals and in the Christian Eucharist, it came to represent the sure and certain hope of rebirth.

Consumed in quantity, it elevated the consciousness of mortals to a state where they not only understood these things, but came within touching distance of the divinities themselves.