Robin Lee tastes the wines of Lorenzo Mocchiutti and Federica Magrini, the creative couple putting Villanova del Judrio in Friuli on the fine-wine map at Vignai da Duline.

When people get interested in wine and start learning about it, they also get interested in maps. It’s part of the learning process. Although there are different approaches to learning about wine, there is one common denominator, which is that just tasting is not enough; geography, history, and cultural traditions determine the evaluation of sensory perceptions. A precious old Madeira might be poured down the drain if you didn’t know what it is supposed to be, and the most valuable wines are sought out for their cultural significance, not just for their taste. But before sinking into a blissful apathy of self-satisfaction, contentedly stroking our diploma distinctions and twiddling our lapel pins, we must also remember that any learning process has its pitfalls, not to say failures and drawbacks. Learning instills prejudices, which are shortcuts to knowledge. We are taught that some wines are better than others, and we think we know why that is so—but the truth is a moving target that must be constantly pursued lest it escapes us.

Physical maps may seem anachronistic in the real world, but they are essential for learning about wine, for understanding the places where great wines come from and how wine interconnects with place. Since the more famous wine regions have better maps, they are better understood. When the same level of detail is both in the wines and on the maps, studying wine becomes most worthwhile. In Burgundy, the phrase les lieux-dits, “the named places,” suggests that a place that is named is special and we should therefore know about it. This is a cycle; you cannot easily know about a place unless it is on the map and it is named, and we value more what we know, just as we spend more time learning about and thinking about what we value.

Lorenzo Mocchiutti is a wine producer in Villanova del Judrio in Friuli, the easternmost region of Italy. Although it is surely one of Italy’s most important, interesting, influential, and historic wine regions, even Italian wine experts often skip over Friuli, because they do not have concrete expectations of its wines or know what they are supposed to be like. There are very few wine experts who can locate Villanova del Judrio on a map. The Judrio, or Judri in Friuli dialect, is a river originating on the Kolovrat Plain marking the border between Italy and Slovenia, where it is known as Idrija. Historically, it defined the border between Venice and the Habsburg Empire and, later, between Italy and Yugoslavia. The name of Lorenzo Mocchiutti and Federica Magrini’s estate, Vignai da Duline, comes from dolina, which in Friuli dialect is a valley—in this case, the riverbank of the Judrio.

Friuli was one of the richest, most strategically located provinces of the Roman Empire. Later, it became Venetian territory, and then it was ceded to the Austrians. Historically, its viticulture has been influenced by France, thanks to the close relationship between the French and the Habsburgs, but nevertheless Friuli as a wine region is complicated and hard to comprehend, partly because we cannot picture it. In response to this challenge, Mocchiutti has taken it upon himself to produce a new and original map of the entire Friuli wine region, to put his life’s work in context. Mocchiutti’s “winescape” is for Friuli’s lieux-dits like the magic portal to the wine world.

Together with his partner, Federica Magrini, Mocchiutti manages Vignai da Duline and has worked tirelessly toward inventing a pragmatic system of viticulture and of mixed cultivation that is informed by a poetic philosophy of wines that not only literally but also figuratively has as its ultimate goal to put Friuli wines on the map. Over the past few decades, Friuli has become famous for so-called orange wines that look to the past for inspiration—and in particular, back to new-old grape varieties and new-old winemaking techniques that are derived neither from France nor from enological institutions. These innovations have influenced all of Italy to such an extent that other, older, different traditions and traces of history are difficult to discern or understand in any context. At Vignai da Duline, Mocchiutti and Magrini have stepped back from the natural-wine debates and focused their efforts on the vineyard, especially the preservation of their vines, some of which are more than 100 years old, and on creating wines that are stable from the outset and therefore do not require further interventions.

Agropunk and permaculture

Mocchiutti and Magrini both come from wine-producing families but found each other along a different path. Mocchiutti, the liberated anarchist-libertarian, founded a rock band, Arbe Garbe, when he was 18 and played bass guitar. The band had a political mission, encouraging the struggle against industrialization and preaching self-sufficiency. Mocchiutti studied medicine, Magrini literature. Attracted by the New Age movement, Magrini became vegetarian, and although she studied biodynamics as part of a deconstruction of the nutritional and food-production system, she was more inspired by a radical political agenda. Biodynamics was unacceptable to her as a vegetarian, and she and Mocchiutti lean more toward the teachings of Fukuoka, the pioneer of permaculture.

“Wine was one of many things for us, and not by any means the most important one,” Mocchiutti explains. “At that time, we were living on a spark of enthusiasm for everything. We thought about rural revival as a political project; the belief in a strong social and ecological ethos, with a focus on sharing. It was also a cultural project. We would go around barns looking for old pieces of farming equipment, trying to put them back to good use.” The Rural Information and Correspondence (RIC) movement was formed in 1997, with the objective of bringing the rural experience to a wider audience and dedicated to the experiment of mutual reliance, barter, and the conservation and exchange of ancient seeds. Helped by their friend, botanist Marco Valečič, they coined the term agropunk, in “an attempt to define the indefinable thing we were aiming to be.”

But Magrini and Mocchiutti were still just a literature professor and a medical student. How could Mocchiutti’s grandfather ever have fathomed that they wanted to be farmers? Nonno had done it out of necessity. He had never believed in it. Mocchiutti and his grandfather had 60 years between them, but their strife came from something else: different values. Thinking, imagining, and planning for wines that would be of outstanding quality but made honestly, with no help from consultants and without “makeup”—for Mocchiutti and Magrini, this was the basis, a necessity; and for Nonno, incomprehensible. As Mocchiutti explains, “At that time, the issue was even more contentious because of the bad reputation of organic wine, which rejects even the smallest corrections to a wine and seems captured by an aversion to gustatory quality. Organic wine must be salubrious, for sure, but unpleasant, if not outright faulty, much the same as with so-called natural wine: excessive oxidation with aromas of rotten apple, or reduction with its hallmark rotten-egg aroma.” Nevertheless, in 1997 Mocchiutti and Magrini became vignerons, the occasion marked by an IVA (VAT) registration in the name Vignai da Duline.

Discovering and sculpting terroir

Duline is the vineyard of Mocchiutti’s grandfather on his maternal side. In 1920, great-grandfather Giuseppe Pizzamiglio, known as Beppo for short, had bought the Duline plot, just outside the town of Villanova del Judrio, between Udine and Gorizia. There were already a few rows of vines, one of which, dating from 1908, is still there. Beppo planted Tocai Friulano and Merlot in 1920, the historic nucleus of the vineyard, and in 1936 and 1943 he planted more Tocai Friulano with, as was customary at the time, a few intermingled vines of Malvasia and Verduzzo that are all still in production today. In 1943, Beppo added one more row to close off the vineyard. It consists of mulberry bushes intermarried with grapevines, which goes all around the vineyard like a French clos. In 1978, an EEC regulation was passed to authorize Schioppettino, Pignolo, Tezzelenghe, and Ribolla Gialla in Udine. Before then, these wines were nothing more than rosso and bianco. Nonno planted his first Schioppettino in 1977, and it is a big source of pride for Duline that those original vines are also still there, in full vitality and productivity.

In the early days of his work in the vineyard, Mocchiutti identified more than 20 grape varieties, each with multiple biotypes, and he microvinified each of the varieties even where there were only a handful of vines planted: Ribolla, Tazzelenghe, Franconia, Riesling, Cabernet Sauvignon. Even when it was just one single vine, the grapes were harvested and vinified separately. It was an immense amount of work, but necessary: “The microvinifications revealed that some wines were good every year, others every three years, others every five years. They became my measure of the terroir. They showed me what to pursue. I took out some vines, but very few. I have never uprooted an entire row. Instead, I did a sculpting and a sewing-up job, vine by vine. I kept a few uncommercial varieties for my own interest, such as Ua di Sant’Jacum, an early-ripening, delicious table variety.”

Mocchiutti was fortunate, because the vineyards he inherited from Nonno had avoided the destruction suffered by so many others in the area from ruinous chemicals and technical equipment that had, at the time, seemed like a liberation from the drudgery of hard work, from the vagaries of weather, and from parasites—but that led to the decimation of soil fertility, genetic material, and the legacy of agricultural skills that is preserved in old vineyards. The reason that Duline’s vines were saved from this destruction was because Nonno had always been wary of the costs involved. Over decades, the agricultural salesforce had beat the pavement night and day to sell him phytosanitary products, machines, and herbicides, but Nonno would always look at them suspiciously and say, “It costs less to do it by hand.” For this simple reason, and not out of any love of tradition or sentimental longings for the past, Duline is one of the few vineyards that has never been exposed to herbicide. Thankfully, Nonno was extremely stingy.

Working to restore the old vines they inherited, and expanding into Ronco Pitotti through a musical connection they shared with the son of its owners, Mocchiutti and Magrini have, over time, come to understand the interconnection of the vine with the surrounding nature and have pursued the highest quality in wine through an approach to agriculture that is emancipated from any ties with synthetic products, which turn a wine estate, in Mocchiutti’s phrase, into “a mechanic’s shop.” Mocchiutti raises alfalfa as a soil fertilizer—which he refers to as his “green cow”—and cultivates bees as a proactive anti-botrytis treatment, as well as wasps and hornets for beneficial yeasts. At Vignai da Duline there is balance with nature, something that eludes the most famous wine regions, since where there is a grapevine monoculture, there cannot be true balance with nature.

In 1997, Mocchiutti and Magrini converted an entryway to the cellar into a tasting room. This simple, small, welcoming area, a fixed point, is considered a place of transmutation and of tempering with judgment and critical appraisal, before a wine is released. The bottles will travel the world alone, but the winemaker’s story, the opinion of the taster, and the inherent quality of the wine are first and irrefutably foremost. And for anyone who wants to learn about the benchmark wines of Friuli and to understand them, the answers are to be found here rather than in any textbooks. Fortunately, there is now Lorenzo Mocchiutti’s beautiful new map to guide us on our way.

Tasting Vignai da Duline

Duline Friulano 2018

Centenarian vines planted in 1920, and some from 1936, offer up a complex palate of nectarine, fresh apricot, and green almond, with a sprightly acidity that is remarkable for such a warm vintage. The fruit is crystalline and pure, attesting to the perfect maturity and health of the grapes from these low-yielding vines. The clarity and freshness of the wine carries through into a saline finish. 2023–35. 93

Duline Pitotti Chardonnay 2016

This Chardonnay from 45-year-old vines is layered and rich, with a peachy-strawberry character ranging from snowy-white, through to the most delicately pink. The bouquet is enhanced by a hint of spicy white pepper and a satisfying, waxy, full-bodied texture balanced with the zest of cool-climate lemons and white peach again on the finish. 2023–33. 92

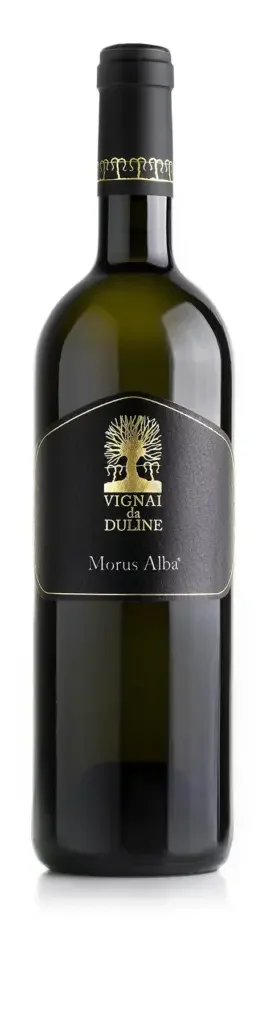

Morus Alba [White Mulberry] 2018

This proprietary blend of old-vine Malvasia Istriana and Sauvignon Blanc is named for a row of vines trained on living mulberry bushes that surrounds the old vineyard, planted by Mocchiutti’s grandfather in 1943. The intriguing nose suggests ripe pear and golden apple, with fresh-mown alfalfa, wild mint, and chamomile. This is a happy marriage of two grape varieties grown for almost half a century together in the same vineyard, in harmony with wildflowers, beneficial insects, and fruit trees. The wine is quite low in acid but nevertheless well balanced with a freshness that rises to the weight and texture. 2023–28. 91

Ronco Pitotti Sauvignon Storico Friulano 2016

From old vines planted in 1979, this has been made as a varietal wine only in the excellent 2016 and 2019 vintages. Pale color. The nose unfolds with lily-of-the-valley, green apple, and white asparagus, showing Old World restraint. The wine is youthful and light on its feet, giving an innate verve and vibrancy. The structure is tight and restrained, with a refined and delicate floral tone on the long, tempered finish. 2023–28. 91

Giallodi Tocai Selezione 2018 (magnum)

A selection from 900 vines of the rare yellow-skinned Friulano clone that Mocchiutti rescued from the original scions. This wine beams with an inner glow of acacia honey and a warm spiciness of ginger and turmeric. Roasted pineapple, walnut skin, and bracing hints of a sour-brewed kombucha, with a rich but taut texture, suggest this exceptional Friulano is capable of long aging, though it already delivers outstanding power and complexity. 2023–35. 94

Ronco Pitotti Pinot Noir 2018

These vines were planted in 1940 and 1980, but the first vintage vinified by Vignai da Duline was not until 2009, after several years spent restoring these old vines nestled in a sheltered nook within the contours of this locally famous grape amphitheater. Opening with ripe raspberries, deeper notes emerge of tar, musk, and pine needles. The alcohol is decidedly low, at 12.5%, and there is an interesting umami note of sun-dried seaweed that creeps in on the edges of the palate, along with ferrous rust and blood. This complex wine is a fine example of Italian Pinot Noir, which can surely hold its own against internationally acclaimed rivals. 2023–38. 92

Morus Nigra [Black Mulberry] 2016

The signature red wine of Vignai da Duline, Morus Nigra is, like its white counterpart, named for the mulberry vineyard planted in 1943. This is deep, dark, and robust, with a Black Forest gâteau richness laced with dark mulberries, ripe purple plums, and sweet damson. The acidity stands firm against an elegant and sturdy tannic framework. The long, persistent finish lingers, with aromas of violet and hints of anise. 2023–38. 93

Ronco Pitotti Pinot Grigio 2012–21

Ronco Pitotti Pinot Grigio 2021

From mature 65- and 40-year-old vines planted in 1958 and 1984. The name of the wine is Pinot Grigio, but the character is more akin to Alsace Pinot Gris. As is common in Alsace (but not in Italy), the Duline whites all undergo full malolactic fermentation, which makes them stable, with no need for filtering, and gives an integrated acidity that evolves with the wine. This has a fine, creamy texture, with concentrated dry extract and beguiling aromas of lily-of-the-valley, ripe yellow pears, cinnamon spice, and warm tennis clay with toasted Brazil nuts. Full and rich, with a crystal-clear purity and freshness that gives way to a lingering smoky haze of barbecued honey. 2023–35. 93

Ronco Pitotti Pinot Grigio 2019

An intense nose, an exotic lily-spice note lifting yellow plums and ripe pears, and a sweeter note of sugar-coated almonds and praline. Finishes long and pure, with hints of litchi and coconut water. 2023–35. 91

Ronco Pitotti Pinot Grigio 2018

Shimmers and shines with a pale-lemon color. Soft aromas of white peony tea and orange blossom entice, with a silky texture of lemon curd. This balances floral and fruit flavors of litchi and golden apple with a solid structure, finishing perfectly dry and satisfyingly full-bodied at 13% ABV. 2023–28. 90

Ronco Pitotti Pinot Grigio 2016

Delicate, exotic candied guava, rosehip jelly, and basil essential oil, with a touch of burned rosemary on the finish. The creamy texture is like almond butter and baked yellow summer squash, flavorsome and rich. 2023–30. 90

Ronco Pitotti Pinot Grigio 2012

Deep gold, with copper glints verging toward the palest of Provence rosé, this mature wine has an unusual bouquet of rosewater and eau-

de-cologne, evolving with savory/spicy hints of fresh tarragon, cinnamon, and cardamom spice, and a waxy texture like white melon. Drink up. 91

Malvasia Istriana Chioma Integrale 2015–20

Malvasia Istriana Chioma Integrale 2020

From vines planted in 1960 and 2005, this cuvée is named after the practice that Duline uses on all its vineyards, where the vines are allowed to grow to their natural length, in keeping with Fukuoka principles of permaculture, without hedging or topping (thus chioma integrale, which means natural canopy). This wine has a green but nevertheless ripe character of ripe kiwi and young parsley, with a savory, saline element of lamb’s lettuce, green walnut, and celery, and notes of sassafras and spicy green peppercorns illuminating the finish. 2023–28. 92

Malvasia Istriana Chioma Integrale 2019

Pale green glints to the gold seem to reflect the tart Bramley apple and salty samphire on the nose. Fresh as a sea breeze, but also indulgent and creamy on the palate, bergamot crème brûlée and burned peaches giving way to a long finish that is refreshing and refined, with watermelon rind and lime macaroon. 2023–28. 93

Malvasia Istriana Chioma Integrale 2018

This wine has ripe, rich fruit that bursts on the palate intensely yellow and green. A sapid spectrum of pineapple, passion fruit, and sweet yellow peach is underlined by a smoky minerality and tones of cigar ash. Stylish, uninhibited, rococo, this wine finishes as zesty as it is luxurious, but also with a refreshing crystal-clear quality. 2023–30. 92

Malvasia Istriana Chioma Integrale 2016

Somewhat closed at first, the 2016 gradually emerges with green apple and gooseberry, and then with sweet and grassy aromas of green peas, asparagus, and clover that gradually unfold. The palate has a heavy layer of beeswax with apple blossom and meadow flowers carrying through to the finish. Drink up. 91

Malvasia Istriana Chioma Integrale 2015

The nose is complex, with white tea, white melon, and green cucumber heralding a waxy-textured palate with notes of guava and fava bean making for an engaging counterpoint between white fruit and herbaceous tertiary aromas. Drink up. 90

Duline Schioppettino 2016–20

Duline Schioppettino 2020

Deep ruby with a vibrant nose that evokes black pepper, gunpowder tea, and matcha. The tannins are soft but present, and there are enticing floral aromas of lily and violet. The spicy and long finish is like a highly enjoyable and lingering peppery embrace from back in the old days. 2023–30. 91

Duline Schioppettino 2019

Fresh raspberry and blueberry dominate the nose, with the sweetness of old-fashioned chewy black bread. On the palate, the wine is structured, bold, and vivacious. The finish is long, with iodine notes, Sardinian myrtle, and roasting juices persisting on the palate. 2023–30. 93

Duline Schioppettino 2018

Dark in color, with bright ruby reflections, this Schioppettino comes from vines planted in 1977, when the variety was officially revived, with some additional plantings added in 2005. Despite its deep color, Schioppettino is a light-bodied and easygoing red wine, this one rich in flavor with dark blackcurrant and blackberry. The acidity is high, and there is some tertiary, old, polished mahogany—seasoned small casks are used for the aging. After some breathing time in the glass, the wine unfurls hints of chocolate and jujube as the initial tartness gives way to a smoky finish. 2023–30. 91

Duline Schioppettino 2016

A hint of brick color on the rim of the glass betrays its age, but this wine is still resilient and flavorsome, with earthy cherry liqueur, mushroom ketchup, and stewed beetroot. There is a tinge of warmth and a faded smooth-satin mouthfeel rustically perfumed with rosehip and lavender. The long finish reveals other intriguing notes of cherry cola and smoked hickory. Drink up. 92

Ronco Pitotti il Merlot 2015–19

From 1920 and 1999 plantings of the rare Merlot rouge red-stemmed biotype, matured in small seasoned casks. Approximately 500 magnums produced in most vintages.

Ronco Pitotti Il Merlot 2019 (magnum)

Imported here during Habsburg times, first planted at Ronco Pitotti in 1920, this historic Merlot is one of a kind. There is blackcurrant, mulberry, mint, and a vivacious richness reflected in the brilliant and deep ruby-black color. Classically proportioned, with a medium body, graceful and harmonious, with impressive length, this is an outstanding Merlot. The penetrating fragrance evokes cedar, chestnuts, earth minerals, and wild plums. Powerful, dense, and elegantly structured, with a judicious extraction of healthy fruit, this wine has immense potential, but patience is needed. 2028–50. 95

Ronco Pitotti Il Merlot 2018 (magnum)

A classic vintage of this wine, the 2018 is light and elegant, yet intense. It is almost diaphanous in its weightlessness, with an opaque magenta color that heralds a complex bouquet of Sachertorte and radicchio. Medium-bodied, with fine-textured tannins and a long, flavorsome finish that is all sweetness and harmony, this is a beautiful example of what Merlot should be. 2023–33. 92

Ronco Pitotti Il Merlot 2016 (magnum)

The 2016 vintage is a rich and balanced example that is worthy to stand alongside any of the great wines made from this noble and frequently undervalued variety. This sensational wine has a dense ruby color to the rim and a luxurious bouquet of cedarwood, cypress, cocoa, and blueberry. Silky textured, with a low acidity and gliding, firm tannins that are stunningly seductive, an unfolding complexity indicates that this deep and vibrant wine is destined to impress for many years to come. The 2016 is just coming into maturity and should continue to gracefully age. 2028–50. 96

Ronco Pitotti Il Merlot 2015 (magnum)

This beautiful, dense, garnet-colored production from a drought-ridden, low-yielding vintage offers up tantalizingly opulent notes of plum, black cherries, scorched earth, and oriental spice. Medium-bodied, with saturated and darkly rich cherry fruit, mild but refreshing acidity, and sweet, fine-grained tannins, this is a beauty that is more approachable than the 2016 and yet should continue to improve for at least a decade. 2023–40. 94