A man of letters who became a man of wine, Nick Belfrage MW was an influential merchant, the most significant anglophone writer on Italian wine of his generation, and one of WFW‘s longest-serving contributors. His friend and sometime traveling companion Carla Capalbo pays tribute.

It might surprise today’s lovers of Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, and Nerello Mascalese to learn that, until relatively recently, Italian wine had no place in the UK fine-wine market. British connoisseurs of the early 1980s saw a lake of cheap Italian plonk, compared it in their imaginations to the Bordeaux and Burgundy their fathers had long bought en primeur, and turned away. If one person can be credited with changing that attitude, it was Nicolas Belfrage MW, who has died in London, aged 82.

Nick, as he was always known, had grown up on both sides of the Atlantic in a family of intellectuals. His father, Cedric Belfrage, was a left-wing writer and activist who had been a double agent for British Intelligence during World War II. His mother, Molly Castle, was a glamorous magazine editor and journalist. Nick’s much older sister, Sally, was also a writer and international social activist.

Nick was born in Los Angeles in 1940 but grew up in the Bronx, New York. Cedric was working in Hollywood in 1953 when he was summoned before McCarthy’s House Committee for Un-American Activities; he refused to name names and was deported in 1955. Cedric and Molly had separated by then. Nick and his mother moved back to London when Nick was 14. After all the family turmoil, the switch to an English public school, St Paul’s in London, was tough. It focused him on European studies, but he never lost his keen interest in international politics and social justice.

The brave pioneer

Nick didn’t plan on a career in wine. He was a man of letters, a scholar of Camus and Dante and the author of three unpublished novels. He studied French and Italian at University College, London, followed by stints living in Paris and Siena in the 1960s, and had come to wine, as many of us do, by enjoying and being curious about it.

As the story goes, it was in 1970, at a poker game in London with an old school friend, Albert Vince, that Nick’s professional journey into wine began. Vince had taken over some grocery stores that became the popular late-

night Europa Foods chain and asked Nick to choose French wines for them. This was at a time when Mateus Rosé, Blue Nun, and flasked Chianti were ubiquitous.

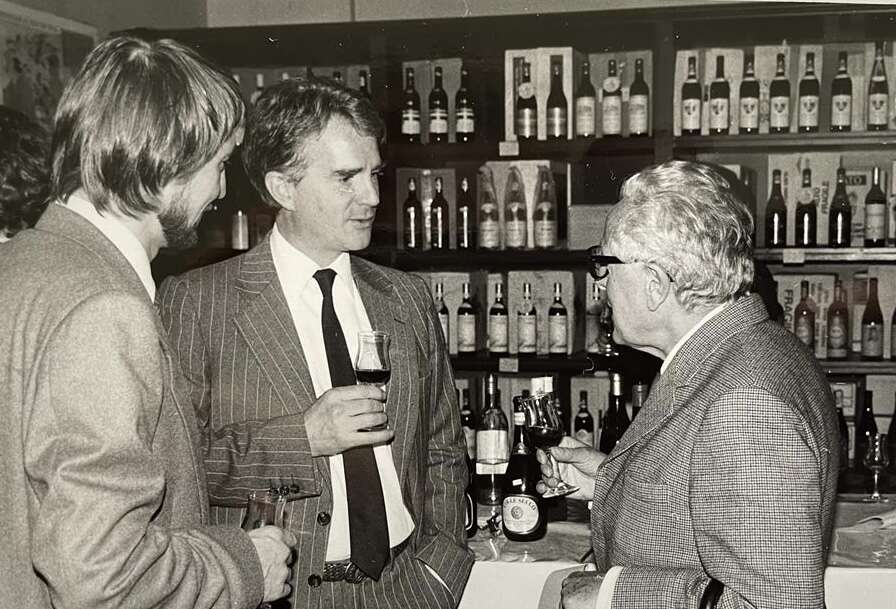

The Grapevine wine shops followed. At Europa, Nick met Colin Loxley, who would become his business partner until Loxley’s untimely death in 2008. As part of their Bretzel group, they opened The Market, in Upper Street, Islington, in the mid-1970s and it was here that Nick began selecting and importing Italian wines in earnest.

From The Market, to Winecellars, a retail and trade warehouse in Wandsworth from 1986 to 94, the focus was ever more on Italy. David Gleave MW, who started working with them in 1984, says Nick’s intuition about a pioneering, all-Italian wine list for Winecellars was a “bold and daring decision at the time, but Nick was convinced it was the right one.” Gleave admits to feeling trepidation about it, but the venture was a success. After Winecellars was sold to Enotria in 1994, Nick and Loxley set up Vinexus, no longer with a physical warehouse but as brokers for Italian wineries in international markets.

As Nick would often say, Vinexus was the perfect vehicle for him: Loxley worked in the office where he was happy running things, which allowed Nick the freedom he craved to travel and explore Italy, visiting wineries and learning ever more about the diversity of Italian grape culture. Nick planned a future continuity for Vinexus by hiring the young Nick Bielak as his partner in 2006; they worked together until Bielak’s premature death earlier this year which came as a great blow. Vinexus continues to trade in the top-quality wines the two Nicks cared about so much.

There’s another side to this chronology. It’s hard to overstate the importance Nick’s vision of Italian wine had on the Italians. In 1980, Nick became a Master of Wine and really found his voice. As he wrote in his first ground-breaking book about Italian wine, commissioned by Jancis Robinson MW and published in 1985, Life Beyond Lambrusco: Understanding Italian Fine Wine, one of the biggest problems the Italians faced in post-War Italy was the lack of a market.

“Nick was the first to bring our Brunello to Britain,” says Laura Brunelli of Gianni Brunelli in Montalcino. “In 1990, we had no idea of how to navigate that market and Nick, with his usual elegant manner, showed us the way.” He and Gleave spotted talent throughout Italy in wineries that later rose to international stardom, including Ascheri, Aldo Conterno, Giuseppe Mascarello, and Vajra in Piedmont, Capezzana, Felsina, Fontodi, Isole e Olena, Selvapiana, and Villa di Vetrice in Tuscany, to name only a few.

.

Belfrage the humanist

Nick’s approach to wine was cultural as much as commercial. Wine was his passion and the focus for much of his intellect. As his nephew, the playwright Moby Pomerance put it: “Nick took the one thing, the least articulated sense that he could call his own… In the hierarchy of importance, it was probably never mentioned in his family, except in passing… He took the simple, profound sensation of taste; and claimed it for his own. And out of that, across the span of his life, he created an entire world. It was a world filled with complexity, subtlety, thought… It was a hidden, secret world, and it was all within a few centilitres of liquid.”

I met Nick in the late 1990s, in Tuscany. We knew each other enough to say hello at Italian wine gatherings. A chance seating arrangement at a Brunello dinner in Montalcino changed that, as we discovered we shared mid-Atlantic backgrounds, the same London school, and a work life dedicated to Italian wines. From then on, we were often in touch.

In 2000, I was staying with winemaker Marco De Bartoli at Samperi, outside Marsala. Nick was in Sicily, too, researching the second volume of his epic A to Z of Italian wines and grape varieties, Brunello to Zibibbo. He rang to say he’d had an accident and his car was damaged. Marco arranged to help and invited him to join us.

It had been a dark period for the pioneering De Bartoli, who devoted his life to bringing Marsala wines back to their former glory after their downgrade to cheap cooking wines with added “flavorings.” He’d made some enemies along the way. In 1995, he was accused on a trumped-up charge of sofisticazione of his Moscato di Pantelleria, and the Carabinieri had sealed the barrels of Marco’s collection of old Marsalas beneath his home in Samperi.

Five years later, the same Carabinieri returned to apologize, explain that he had been absolved of the spurious charges, and reopen the cellar. Nick and I were there shortly after this, and we were taken down below by Marco’s enologist son, Renato. Here’s Nick’s account from the book of that memorable day:

“I was […] given a comprehensive tasting, the first anyone had had for five years since Marco himself had not been able to bring himself to face his neglected babies – if you can call these ancient brews ‘babies’. I can only say that I was stupefied by the range of flavours and aromas on offer from these extraordinary wines, from mineral and medicinal (iodine) to caramel and toffee, from spices and herbs to nuts and dried fruits, and around and back again in a cyclical swirl of tastes, smells, and sensations.

“It was only then, I think, that I fully understood the thesis that Marco had spent his life trying to demonstrate, i.e. that ‘Marsala’ […] is indeed capable of being, not just a good wine, but truly great wine, far greater than some of the alcoholic fruit juices that are held up as representing excellence in our superficial times; these, for me, indeed, put wine in general alongside great painting and music as one of the divine miracles of our existence. Much is spoken about wine as an art form, but there is very little on the level of Turner or Mozart. These wines had that kind of power.”

“Sometimes it takes the look of an outsider to recognize things we can’t see about ourselves,” says Giuseppe Mazzocolin of Felsina Berardenga. “Nick saw Italy from a humanist perspective. He understood the connection between our wines, our landscape, and our history. When he tasted wine, he had a deep but clear and joyous way of expressing that experience—from the idea behind a wine, to the sweat on the brows of those who made it—and we’re so grateful to him for that.”

Nick leaves two remarkable daughters from his marriage to Candida de Melo: Beatriz—a potter and champion of artisan craftspeople in Japan, Afghanistan, and Morocco—and Ixta—a cookery writer and chef. They were his pride and joy. He was supported, fed well, and loved by an extended circle of family and friends in the final years of his co-existence with Parkinson’s. When I asked him, a few months before his death, if he was still drinking wine, he replied with customary irony that, sadly, wine was abandoning him—