Anthony Rose reviews The Oxford Companion to Wine (fifth edition), edited by Julia Harding MW, Jancis Robinson MW OBE, and Tara Q Thomas.

There is a magnum opus that has undergone several editions since its first publication. Subsequent editions have primarily involved changes in spelling, grammar, punctuation, and formatting, but the fundamental content has remained pretty much the same over the years. Or should I say, over the centuries, because I am talking about the King James Version of the Bible, first published in 1611. The magnum opus here, on the other hand—or “Jéroboam opus,” as one Twitter wit (X wit?) called it—looks substantially different from its first outing in 1994. But are there more than simple tweaks from the fourth to the fifth edition of The Oxford Companion to Wine?

In the preface, Julia Harding MW, joint editor with Jancis Robinson MW, anticipates the question: “The world, and the world of wine, has changed a great deal in the eight years since the fourth edition was published, and every single entry has been reviewed and updated to reflect those changes.” She continues: “With a total of more than 4,100 substantive entries, including 272 new ones, more than 100 new expert contributors on all aspects of the glorious and diverse world of wine, we have for the first time breached the one-million-word mark.”

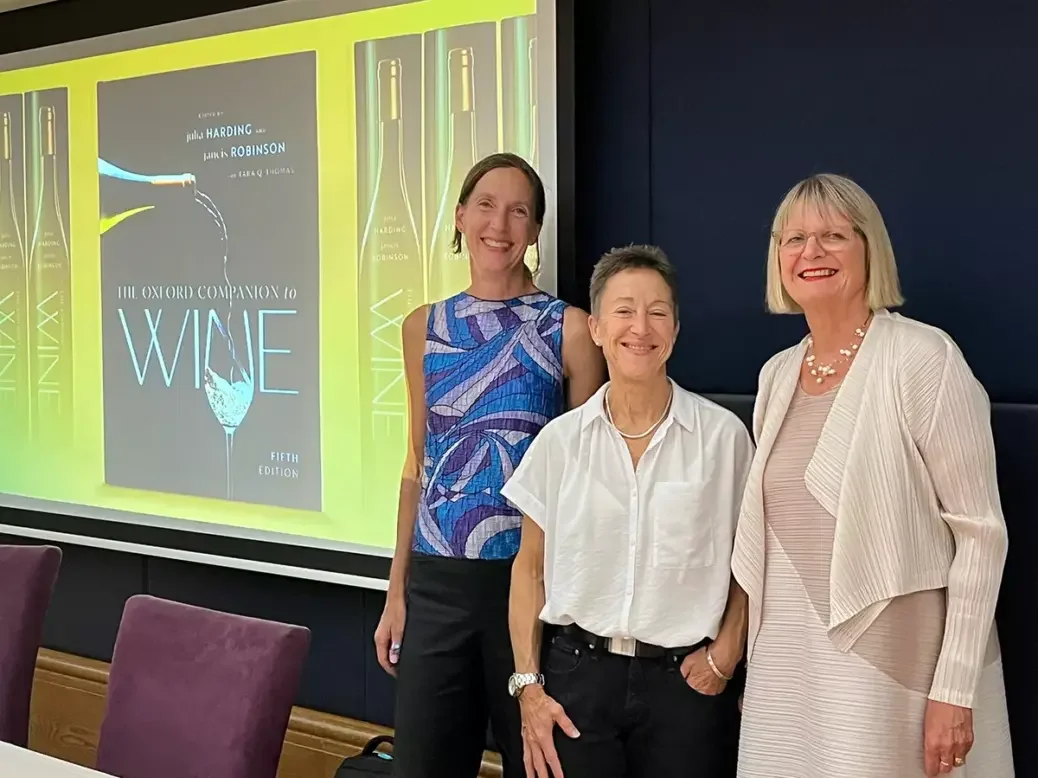

Perhaps the most striking, if not immediately obvious, change has been in the editorial team. The Oxford Companion to Wine is Jancis Robinson’s baby. The Queen Bee and OBE of wine has been at the heart of the Companion since its inception in 1994, bringing on board Julia Harding for major sections of the third and fourth editions. This fifth edition marks a departure, with Jancis effectively handing the editorial baton to Julia—who has overseen and edited topics including viticulture, enology, labeling, packaging, academia, and grape varieties, and who is responsible for 50 percent of the editorial—and to Harding’s choice of assistant editor, Tara Q Thomas, whose contribution, spanning an expanded version of the Americas and other areas, runs to 40 percent of the fifth edition.

“I can’t tell you how delighted I am to put my 3.2kg [7lb] baby [versus 2.85kg (6.3lb) for her fourth offspring] into such capable hands,” says Jancis. She is one of the most effective, albeit cautious, delegators in the business, as we know from her direction of jancisrobinson.com, so the seriousness of purpose in this changing of the guard to two of the most charming assassins of wine editorial inspires confidence.

I attended the launch of the fifth edition at the St James’s Room at 67 Pall Mall in London (a launch liberally wined, in a nice touch, by Hundred Hills Winery in Oxford). “Fortunately,” not all 267 contributors were there, because they would not have been able to fit into the space.

Jancis, Julia, and Tara were all at pains to point out the astonishing expertise of their contributors. However, Oxford University Press has become accustomed “to academics who are simply thrilled to be published,” says Jancis. And The Oxford Companion to Wine is now so prestigious that contributors forgo a fee for their efforts, instead opting for the glitter sprinkled on their resumé. Well played, OUP.

There isn’t enough space here to list all the distinguished contributors. In fact, it would be more economical, if less kind, to mention those who didn’t make the cut, but special mention should go to the distinguished advisory viticulture editor, Dr Richard Smart, and his equally respected enology counterpart, Dr Valérie Lavigne.

The Oxford Companion to Wine: New from glou-glou to zero-zero

Before the A–Z section of the book, two helpful pages at the beginning list the new entries, which include, somewhat enigmatically, ants, bench, finish, glou-glou, and parcel, as well as names, words, and terms you have to remind yourself to look up if only to marvel at how you ever managed without them. These include: biogenic amines, Cangas, CERVIM, curettage, flysch, haloanisoles, Kreaca, Negoska, pervaporation, piperitone, rachis, stabulation (“look it up when you get the book,” says Julia), Talha, vino de tea (not what you think), MGA, Würzelecht, and zymurgy, the latter self-deprecatingly described as “a word more useful in Scrabble than everyday life.”

There are names whose very mention brings sadness—the dear departed Steven Spurrier and Jim Clendenen—and, more cheerfully, living legends who thoroughly deserve their induction into the pantheon of fame: Randall Grahm and Warren Winiarski. There are words that should be accompanied by a “groan” emoji—influencer, celebrity wine, unicorn wine, and, yes, wine critic—and entries promising enlightenment on burning issues of the day, and I don’t just mean wildfires: blockchain, carbon footprint, drones, low-intervention wine, no-till, regenerative viticulture, NOLO, zero-zero, and, of course, NFTs and artificial intelligence. It would be impossible to finish this introduction to new entries without welcoming to the fifth edition the brown marmorated stink bug or reporting that robots have invaded the pages.

Climate change is viewed with great importance, as illustrated by the 224 references to it in the fifth edition versus the 114 in the fourth. The section on climate change and its impact on wine and viticulture brings in a scary summary and chart from the 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Among the entries, Julia singles out for importance trunk diseases such as esca, the spread of Pierce’s disease to Europe, heatwaves, wildfires, antitranspirants, and AI.

On a more positive note, there is plenty to be said on regenerative agriculture, sustainability, biological treatments for pests and diseases, the vine’s own mechanisms (such as epigenetics) for adapting to climate change, and the increasing awareness of wine’s carbon footprint—the need to first measure and then reduce it. On grape varieties, the editors admit that they can’t be as comprehensive as Wine Grapes, which actually runs to even more pages than the Companion, but from Altesse to Zweigelt, there’s still a wealth of information, and the book also adds new varieties gaining in currency such as Kydonitsa, Vidiano, Lilioril, Yamabudo, and several that have been bred for resistance.

According to Tara Thomas, “climate change and human creativity have pushed the borders of the wine world to include places never before included in the Companion.” And so we see for the first time the inclusion of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Norway, whose entries are all written by residents of those countries. We are given insights into the emergence of Gabon, Togo, and Uganda, among 15 other African countries.

New latitudes are explored along with new elevations, with entries on Peru, Colorado, and New Mexico, as well as each of the DOPs of Tenerife. Mexico and New York State, which were only just coming into their own in the last edition, get a full update here, by Carlos Borboa and Maiah Johnson Dunn respectively. South American coverage extends into the remote southern reaches of Patagonia and even out to Easter Island; and Israel now shares the spotlight with an entry for Palestine. Is there nowhere on this planet that the vine has not put down roots? Possibly, but if there is, they will have to wait for the sixth edition.

Topics of contemporary interest, such as natural wine, have been substantially updated. Thus, a new entry from Alice Feiring (previously by Monty Waldin) is thorough and current, and while Alice is a well-known natural-wine proponent, she is also fair, going so far as to quote Robert Parker’s view of natural-wine advocates as “terroir jihadists.” California and Australia get more of a look-in this time round thanks to what Tara Thomas calls an A-team of local writers reporting from their home regions. The advantage of this expansion is that it gives a more personal voice to many of the new entries, as well as making the fifth edition more global in reach and outlook.

Etna gets its own full entry for the first time, while (to give just a couple of examples), appellations and companies such as Taurasi and Changyu, which made an appearance in the fourth edition, have been expanded and brought up to date. Putting minor but significant entries under the microscope across the board, it’s possible to discern that much has been tweaked and updated without fuss to take account of changes such as a growing vineyard area, a new trend, or a significant new player in a wine region. Rather than the headline changes, it’s these subtle but important updates that underline the argument for forking out the not-unreasonable sum of $65 / £50 / CA$80 for the fifth edition.

Almost faultless

It is virtually impossible to find fault with, or gaps in, a work that’s been refined and updated for the fifth time in less than 30 years. However, as Julia says at the start, everything changes quickly in the world of wine, and between putting this volume to bed and its publication there will be new topics and issues that will have to await the sixth edition. Among them, it would have been good to see a bit more than just “Marselan could become China’s signature variety,” because the results from regions such as Hualai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang suggest that it’s now close, if not there. While Harlan is a new entry for Napa, and California cult wines mentioned also include “Screaming Eagle, Sine Qua Non, Colgin, Araujo (now Eisele), Dominus, Opus One and Shafer, Spottswoode, and Heitz,” the Jackson Family’s Lokoya and Vérité, which, arguably, hold equally iconic status, don’t get a look-in.

There are one or two other entries that could have been updated—en primeur, for instance, to show the changes in attitudes toward, and the impact of, Bordeaux en primeur, the growing influence of La Place de Bordeaux beyond the wines of Bordeaux, or the proliferation of urban wineries, not least in the UK. The maps will show you where places are, but at the risk of cannibalizing The World Atlas of Wine, which does have much more terroir detail, I think a next edition might helpfully introduce topography and so give you, at a glance, more terroir information on altitude and exposition. You would think that this could easily be done where a map—such as Chile, for instance—takes up a whole page.

Thanks to its alphabetical format, The Oxford Companion is a doddle to use and a pleasure to browse, with the added advantage that the many cross-references in each entry are denoted by small red capitals. Wine countries have their own entries, and some regions have entries for specific appellations, as do “individual people, wine producers, and properties which have played or are playing an important part in the history of wine.” Useful appendices include an updated list of all significant appellations, along with details of all the grape varieties specified by them, and there are also appendices on total vineyard area by country, wine production, and per capita consumption. These are OIV figures, so vineyard area and production include table grapes and raisins, hence the prominent vineyard size of, for instance, China (third) and Turkey (fifth).

Sandwiched between Belgium and Zimbabwe, the UK is 80th on the vineyard area list—cue “laughing” or “crying” emoji, depending on your point of view—but, speaking as an impartial Brit, not 80th in importance, and at least we do our bit for consumption, where we are a not-dishonorable 23rd. The Companion rather pays lip service to pictures, but I wouldn’t criticize it for that or for an absence of heart or passion, for that matter, because it’s not a book that’s meant to wear its heart on its sleeve. It is in essence an encyclopedia that will enable you to tell your Camel Valley from your Carmel Valley, your Château Latour from your Louis Latour, your Pignatello from your Pignoletto. It is a work of reference and an authority; in fact, I don’t think I’m going out on a limb to say that the fifth edition of The Oxford Companion to Wine is the work of wine reference.

The Oxford Companion to Wine (fifth edition)

Edited by Julia Harding MW, Jancis Robinson MW OBE, and Tara Q Thomas

Published by Oxford University Press

944 pages; $65 / £50