David Schildknecht reviews The New French Wine: Redefining the World’s Greatest Wine Culture by Jon Bonné.

In 2013, Jon Bonné, then wine critic with the San Francisco Chronicle, received international attention for his book The New California Wine. A year later, he announced plans to cover France in a similar way. By the time imminent publication of The New French Wine was announced, the book was eagerly anticipated and represented four years of intensive research. Over the subsequent four years, publication kept getting pushed back, for the professed sake of further research, travel, and editing. Given what resulted, the wonder is that so much was accomplished in well less than a decade (during which Bonné’s The New Wine Rules also appeared).

One doubts that there has been another wine book like this. By virtue of the facts that it comprises 864 pages of fine print in two volumes—“The Narrative” and “The Producers”—and that it weighs 8lb (3.6kg) in boxed hard copy, The New French Wine is already unique. More important, one seriously doubts that there has been so multilayered an account of la France viticole. Bonné musters and adeptly mines two centuries’ worth of ampelographic, viticultural, and enological literature, which time and again yields not just fascinating (and what even knowledgeable wine professionals will sometimes find unexpected) insights into past practices and perceptions, but also signposts to roads not taken or little traveled, yet well worth exploring. And for following those paths broken by French wine growers over the past quarter century, it’s scarcely possible to imagine a guide informed by more perceptive, let alone comprehensive, conversations and tastings with a greater number of them. Volume One covers each region from its geological, geographical, climatic, historical, cultural, and wine-political perspectives, and then—even for some little-known or nowadays sparsely farmed parts of France—village by village, frequently vineyard by vineyard.

Using input from geological professionals, Bonné exposes France’s literal underpinnings in rare detail. And if discussion of rocks is given preference over accounts of soil or of mechanisms by which either of these might influence flavor, and over an impression at times conveyed that geological age somehow confers vinous authority, Bonné is correct in noting that this reflects long-standing, almost reverent perceptions and presuppositions shared by France’s growers and agricultural authorities, as well as tastemakers. And French self-perception is at the heart of Bonné’s narrative, extending well beyond matters normally thought to have vinous import. Not that provocative opinions on wine ever disappear for more than a few pages at a time.

One suspects that some keen observers of France, especially natives with relevant professional expertise, will rankle at the extent and tenor of Bonné’s armchair sociopolitical—occasionally, even philosophical—musings, while enophiles may find some of his attempts to render these relevant to wine a stretch. Yet, undeniably, Bonné’s willingness—indeed, obvious predisposition—to trespass the boundaries of conventional wine commentary by delving into issues of national and regional identity is part of what will keep readers attentively, even eagerly, turning 450 pages of discursive text. (And that’s just Volume One.) As for relevance, insofar as there exists a French self-image or a French soul, wine occupies an unprecedented place therein, and it is thus inextricably entangled with equally profound non-vinous roots. Soulcraft and self-imaging are in essence what’s being practiced by those vignerons whom Bonné chooses to canvass in detail, people who seek to connect with the often nearly forgotten grapes and methods of what is sometimes envisaged—including, at times, by Bonné himself—as a paradisal pre-phylloxera past, but no less to connect with a contemporary consumer base whose size seems to be evolving inversely with its enthusiasm and fashion-consciousness.

Volume One’s geographical sweep is interspersed with essays on topics ranging from patrimoine as a seminal concept, “The Rise and Fall of Appellations,” back-to-the-future viticulture, and climate change, to detailed considerations of natural wine, the influential career of Jules Chauvet, and Gamay’s place in the world of grapes. (“Gamay, it is increasingly clear, is the red grape of the 21st century,” writes Bonné in one of his occasional evidentially underdetermined overstatements.) Dozens of sidebars offer insights on a similarly diverse array of topics, including many technical matters too little understood even by the professed wine-possessed—ranging from geological nomenclature, through vinificatory minutiae, to French land registration and inheritance law. The sheer informational density of Bonné’s tome and the detail of his accounts of rocks, vines, vineyard management, cellar practices, wine law, and the economics of wine (too often neglected in reference books) do not by any means preclude a highly colorful as well as personal narrative, thanks in part to the framing as a years-long road trip. (Those of us not sharing the author’s reference points of English punk, American rock of the waning 20th century, and contemporary US celebrity culture—or, for that matter, readers ignorant of what counts as hip in today’s wine scene and beyond—may find themselves turning to Google for interpretive assistance.)

For all of its explanatory detail, though, only readers already versant in wine will find this book self-contained. A mere two sentences near the onset of Bonné’s Champagne coverage, for instance, presuppose knowing what distinguishes a basket press from a pneumatic bladder press, what constitutes a press fraction, to what “Coquard” refers, and what sort of apparatus constitutes its “modern incline equivalent”—none of which matters are further addressed.

Purposeful provocation

At every stop on his strenuous tour de France, Bonné tries to capture the mood of individual viticultural regions, what has helped or held back their commercial success, and above all what local forces for change he deems progressive and constitutive of “the new” viticultural France. These often-provocative attempts are never less than deeply thought through, though seasoned observers are likely to take issue with some of them, and Bonné’s overarching theme of renewal is a lens capable of distortion. His storyline consistently contrasts fledgling, forward-thinking revival with irresponsible, late 20th-century industrial mediocrity, and conflicting evidence is sometimes ignored.

Vine diversification with an eye toward once-important but now-neglected cépages—to be sure, a laudable and fascinating aim—is treated as an implicit standard of integrity, while late 20th-century mercantile success is routinely taken as symptomatic of the opposite. It’s thus unsurprising that Bonné’s account of Sancerre—which has relied on the same two grape varieties since long before phylloxera, and which established commercial ubiquity in the late 20th century—comes in for especially scathing treatment. Success during the 1980s in establishing international recognition for this appellation is said to have resulted in “the usual story”: “yields go up […] and winemaking becomes overly technical and null [sic].” But growers whose wines of the 1980s and ’90s could scarcely be deemed technical or dull (if that’s what was meant), and whose estates still excel today—Gérard Boulay, Pascal and Nicolas Reverdy, Claude Thomas—go unmentioned, while even the Cotats and Edmond Vatan only appear in Bonné’s Volume Two.

This is far from the sole instance where a misleading impression is conveyed that a region’s revival or awakening of quality consciousness is strictly a 21st-century phenomenon brought about by those individuals whom Bonné has chosen to profile. For example, when a roster of nearly 100 Champagne producers omits Egly-Ouriet, and when Dominique Lafon is (rightly) praised for “bringing long-needed attention to the [Mâcon] and forcing some hard thinking about quality,” but there is not a word about Jean-Marie Guffens, who was doing the same 20 years prior, you know that Bonné views innovation from a temporally restricted perspective. He refers to “the Mâcon’s rather slim roster of estate-bottled wines,” but omits consideration of Daniel Barraud, Christophe Cordier, Robert Denogent, Olivier Merlin, or Jean Thévenet, all of whom were already widely recognized beacons of Macônnais quality by the 1990s.

Bonné is hardly the first commentator to view Alsace as laboring under an identity crisis, but his harsh assessments—avowedly inspired by his conversations with Jean-Michel Deiss, a notorious contrarian whose strong opinions rest on intriguing but contestable principles of aesthetics, viticulture, and metaphysics—may strike even nonpartisan observers as broad-brush and wide of the mark. “[D]ozens of grand crus,” are, Bonné firmly insists, “more than anyone can reasonably parse.” There are 51—but for nearly twice the vine surface of the Côte d’Or (with its nearly three dozen grands crus and almost 500 premiers crus), two and a half times the Côte d’Or’s north–south extension, and incomparable geological diversity. Bonné finds “a certain monotony of flavors and styles in too many wines these days.” But even abstracting from the diversity inherent in eight principal grape varieties plus blends, divergent approaches to residual sugar, malolactic transformation, and élevage already practically guarantee a certain multiplicity. And, to pick merely three among many possible pairs of prominent Alsace producers—none of them profiled in Bonné’s Volume Two—it would be hard to imagine much greater stylistic divergence than between Emile Beyer and Léon Beyer of Eguisheim; Dirler-Cadé and Schlumberger, farming the same Guebwiller sites; or Rolly Gassmann and nearby Trimbach.

An at-times contrarian approach is practically predictable—but that’s not to say unwelcome. Bonné devotes considerable space in his Burgundy chapter to Aligoté and to the Hautes-Côtes. But the case he makes for that until recently underappreciated grape and subregion could scarcely be more engaging, persuasive, or timely. What might initially seem like outsized attention paid to “the outer rim” of Bordeaux (a region that, on the whole, he condemns as “uninterested in […] retooling for modern times”) or to such far-flung viticultural outposts as Aveyron, where Bonné ends his tour, may no longer seem inordinate after reading his eloquent accounts, not to mention after making direct contact with the wines. Again and again, Bonné’s treatment reflects “a belief”—shared by the growers he champions—“that even modest wines deserve consideration and making them requires self-reflection.” And all of that helps to render his recommendations valuable even to wine lovers on a budget.

France’s “is a wine culture that constantly moves and shifts,” writes Bonné, and its “vitality and constant need for improvement [make] it the world’s greatest […]. That said, choices had to be made about who represents this [sic] new culture.” In other words, notwithstanding the constant flux and vicissitudes of French viticulture and taste, into which Bonné’s copious historical musings offer such great insight, from a present perspective, he posits a singular “new culture” into which any given development or vigneron fits or doesn’t. At times, an avowed agonizing over whether or not leaves one wondering why Bonné can’t admit that the question, if not fatuous, is at least moot. Of Zind Humbrecht, for instance—an estate whose moves and shifts and striving for improvement have been conspicuous across four decades, but not among those categorized in his book as “benchmarks”—Bonné writes: “The question that I often ask is whether the wines point more to Alsace’s past, or its future, and I tend to land on the former.” Why ask? But, if one must, isn’t the answer rather obviously “both”?

Readers could be forgiven for concluding that membership in Bonné’s new culture rests on a relatively small set of criteria: practice of organics or biodynamics, minimization of SO2, diversification of vinificatory vessels, and a preference for wines said to exhibit levity, freshness, animation, and above all—empirically imponderable though this concept is—clarity. That these criteria reflect significant contemporary trends is undeniable. Whether they represent adequate touchstones of progressive winemaking—much less criteria likely to be accorded comparable significance a decade from now—can be debated. The weight placed by Bonné on exploration of neglected traditional grape varieties seems less debatable, in the daunting face of climate change. What he quotes Julien Castell of Domaine Castell-Reynoard as saying about planting arch-traditional varieties that were nonetheless never incorporated into the Bandol AOC should arguably be a rallying cry for winegrowers throughout France and beyond: “We don’t need to close the door. We need to open the door and add diversity.”

But as valuably thought-provoking as the polemical overall arc of Bonné’s narrative is, it is the formidable accumulation of details that clinches his book’s indispensability. This is well illustrated by the more than 800 producer profiles delivered in his nearly 400-page Volume Two, most of which canvass every bottling of a given grower’s portfolio, replete with vivid descriptions at times almost as delicious linguistically as the wines are gustatorily. Of Lelarge-Pugeot, a little-known domaine in the previously obscure Champagne hamlet of Vrigny, Bonné writes with characteristic enticement and effortless display of intimacy: “Even more fun is the[ir] Blanc de Meuniers […] which shows off both the grape’s floral and red fruit side as well as sweet lime and almond. It’s the joyous wine you’d want from a village that leaves Christmas ribbons on its bushes through the end of January.”

Refined execution

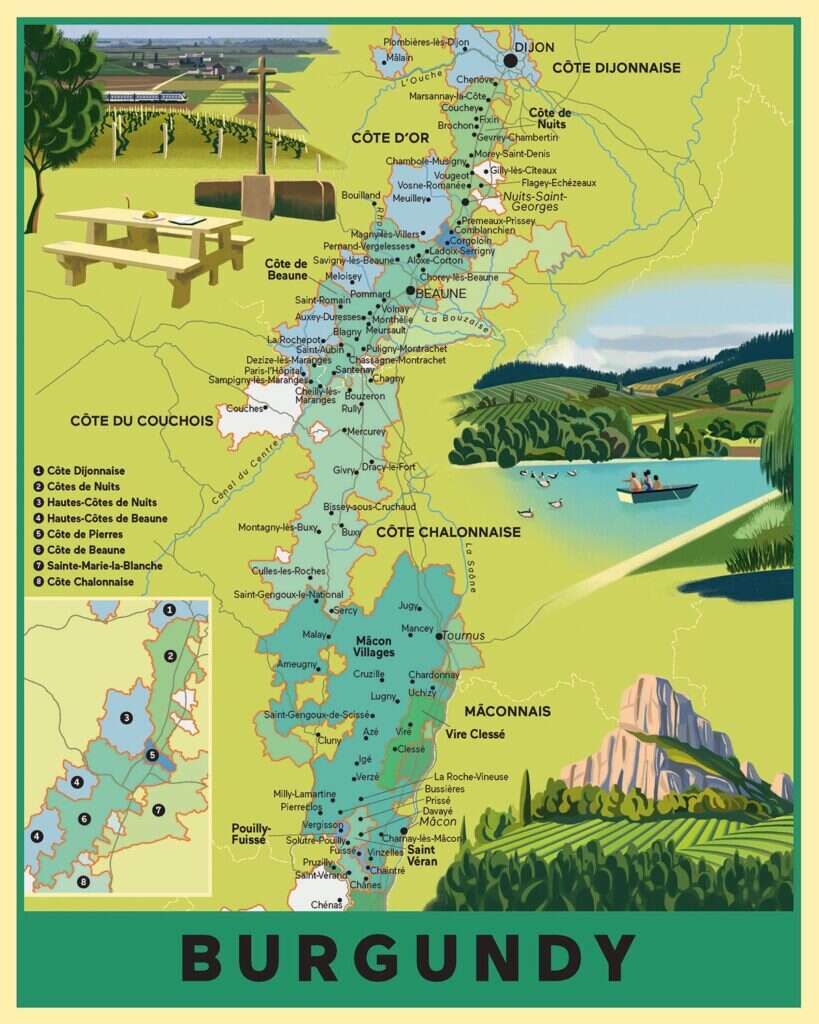

Accompanying each major region covered by Bonné is a map that is maximally informative yet whimsically retro in design, with occasional departures from conventional geographical categories—conspicuously including the separation of Roussillon from Languedoc and a nine-part subdivision of Champagne—being well deserved. Cross-referencing within the text is comprehensive, and the index is admirably thorough—both especially helpful features in a book of this size and scope. A scrupulous search for typographical errors comes up virtually empty-handed, a striking departure from what has sadly become conventional practice at many prestigious publishing houses.

A singular disappointment of The New French Wine—and one that could yet be rectified online—results from the decision (which Bonné reports was fraught) to leave Susannah Ireland’s hundreds of accompanying photographs uncaptioned. Only someone with intensive recent on-site experience in every corner of viticultural France—which would be exactly who else?—is likely to recognize even three quarters of the people and places depicted, whose images only occasionally appear in such direct proximity to a relevant text as to permit reliable conjecture on the part of less experienced readers. Lack of identification is especially frustrating given that these photographs are so gorgeously evocative and include so many haunting portraits—a description that also fits Bonné’s text. ▉