Possessing determination, resources, and an expanding professional network have their rewards, Roger Morris finds as he meets Rutger de Vink on his Virginia estate.

Fifteen vintages ago, Rutger de Vink made his intentions known to create an American cru in the hilly Virginia countryside west of Washington, DC. His would be an authentic cru—a grand vin from a grand wine estate—one patterned after the legendary crus of Europe, Bordeaux in particular, and one that would be recognized by de Vink’s peers as a worthy member of their international society and, eventually, by wine collectors and the secondary market as well. After some deliberation, he accepted a colleague’s suggestion that he name his budding cru “RdV,” reflecting both his own initials and the French slang for “rendezvous.”

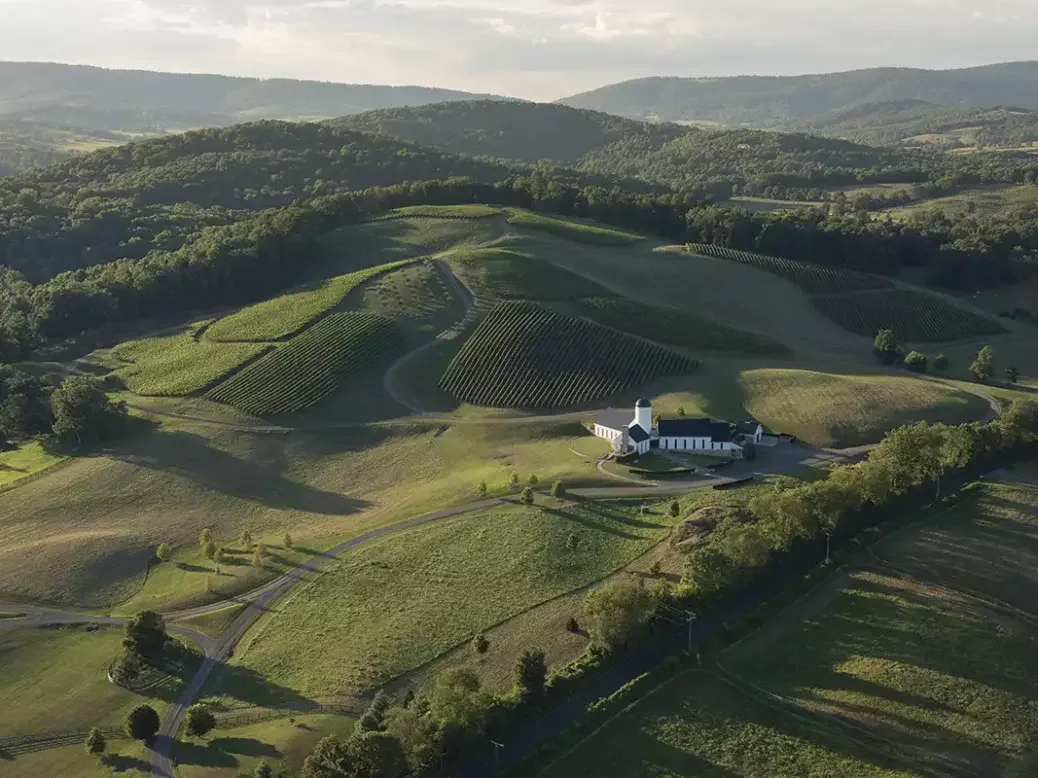

Thus far, de Vink appears to be succeeding in his mission. His cru-in-the-making is today an estate-in-full—one that greets visitors with a pristine white winery topped off with a farm-style silo (“The French have their turrets, we have our American silo,” de Vink says) set in the middle of an amphitheater of undulating vines near the small farm village of Delaplane in the foothills of the Appalachians, as bucolic yet as pristine as a Constable painting. Professional wine voices as diverse as Jancis Robinson MW, Eric Boissenot, David Ramey, James Suckling, and Robert Parker have all praised de Vink and his red Bordeaux blends, produced in the Bordeaux manner with a grand vin (Lost Mountain) followed by a second wine (Rendezvous) from the estate’s 16 acres (6.5ha) of vineyards. The current vintage of the grand vin sells for $230 a bottle or about €200, far above what de Vink’s neighboring vintners, even well-regarded ones, charge.

To be sure, there have been many great American wines produced on the West Coast and some very good to great ones on the East Coast as well. But few, if any, American wine growers have set out to create a singular cru in the sense of a superlative estate wine that would, as a brand, also reflect its terroir and its estate in a totality, a single thought or entity, in the way that one thinks of Haut-Brion or Ausone or Cheval Blanc as brands beyond the bottle.

And unlike others of similar vision and means who might decide to build an estate slowly and quietly, step by step, de Vink assumed the identity as the owner of an established cru from his first vintage and has worked d/iligently to expand both the actuality and its image. This approach could be viewed as a quixotic one, quick to be ridiculed—after all, a world cru in Virginia?—or as an act of great hubris, or perhaps simply the method of a creative and resourceful person who knows what he wants and is confident he knows how to get it.

“Some other local winemakers were taken aback at first—‘What’s this?’—and the restaurants in DC were not exactly jumping up and down to buy the wine,” de Vink says across a tasting table in RdV’s small but modern cellar on a recent spring morning. “People were slightly skeptical, and we had to justify what we were doing. But now, most people in the industry—wherever you are making wines—realize you have to have benchmarks for everyone to profit. In any industry, you need flagships.” De Vink has enthusiastically seized on the role of being that benchmark.

Rutger de Vink: A man at home with who he is

At 53 years of age (he was born on August 9, 1970), Rutger de Vink is a striking figure—tall and athletic, with a sculptured face and lanky, dark blond hair worn in the mode of a California surfer. Casually dressed, he is open and forthcoming, not at all arrogant as one might expect from his statements, but instead eager to discuss how his vision is becoming a reality—a man at home with who he is.

Much in the style of the owner/director of a Bordeaux estate, de Vink remains closely involved in all levels of the winery but nevertheless depends heavily on his winemaker and friend, technical director and recent MW Joshua Grainer, who has been with him since the beginning. As we talk, Grainer leads us through a four-vintage tasting of Lost Mountain estate wines—2009, 2013, 2016, and 2019. While Cabernet Sauvignon is the lead variety in all the blends, the amount varies considerably, from a high of 97 percent (the rest Merlot) in the 2016, to as little as 53 percent (with 27 percent Cabernet Franc and 20 percent Merlot) in the 2013.

In the glass, the wines seem almost immune to their ages, all lovely and all bearing a very similar structural approach, their differences seeming to reflect vintages rather than shifts in style or even the result of varietal composition. All are lean without being spare, have concentrated yet very enticing dark blackberry fruit, a few earthy and savory notes, well-integrated tannins, and great length on the palate. The vintage differences are mainly in accents. The 2019, not surprisingly, is more floral; the 2016 is more supple and its tannins more noticeable; the 2013 has a bit more flavor complexity, with chocolate and earthy components; and the 2009—even though it is only the second vintage and from young vines—is perhaps the most concentrated in its fruit, while avoiding being too extracted.

“We’re planted to about half Cabernet Sauvignon, and a quarter each of Cab Franc and Merlot, with a little Petit Verdot,” says Grainer, who was a professional forester before being lured into wine about the same time as de Vink. “We’re fairly simple and straightforward in our approach,” he says. “We have 12 fermentation tanks, one for each of our 12 plots, and we have a very strict sorting program, including an optical sorter.”

“We decided to use commercial yeasts for fermentation,” de Vink says, cutting in. “I can understand using natural yeasts with Chardonnay or Pinot Noir in Burgundy, but when people say they want to be ‘natural,’ I ask, ‘Why?’ as I do with most things in winemaking. Commercial yeasts work better for us, and they also take less time than natural yeasts.”

Grainer continues, “Eric [Boissenot, who does the winery’s blending—more about that in a minute] likes a profile of low intervention, so we just do pump-overs. He also likes cooler fermentation, about 82°F (28°C). Then we add about 5 percent press wine back in when we blend.” The wine spends about 22 months in barrels, usually about 70 percent new French oak, plus a year in bottle before release. A consultant employed before Boissenot insisted on stressing “power,” Grainer says, and the two men share a grin of remembrance. “The idea was that power proves quality, but we’ve overcome the insecurity of feeling that we had to have power for power’s sake.” Fruit from Virginia terroir, he notes, “is sweeter than Bordeaux, but not as sweet as California,” though he is quick to add, “We build a wine in blending off its structure, not its flavors.”

Altogether, the winery produces about 2,000 cases a year, the bulk of it sold via a subscription list. In addition to the Lost Mountain and Rendezvous first and second wines, de Vink also makes a house wine called Family & Friends rather than bulking off the leftover wine.

De Vink is the first to admit that he has relied heavily on networking with a broad coterie of accomplished colleagues, both in wine and related endeavors and particularly from Bordeaux, in making crucial technical and brand-building decisions. For example, in 2002, shortly after he abandoned corporate life but six years before he made his own first vintage, de Vink became a stagiaire at Cheval Blanc in Bordeaux. There he met and was befriended by fellow Dutchman and Cheval Blanc consultant Kees Van Leeuwen, who suggested the RdV name for de Vink’s winery instead of calling it Lost Mountain, at the time the trending candidate.

The same sort of networking resulted in an early bottle of RdV from three-year-old vines somehow reaching the attention of Bordeaux’s premier consulting guru Eric Boissenot, who was impressed with what he tasted. “I had never met Eric, but he contacted me and said, ‘This is a vin de terroir. I’ll do your blend,’” de Vink recounts gleefully, still somewhat amazed after all these years. It was an offer de Vink did not want to refuse, and Boissenot has been RdV’s consultant and de Vink’s mentor ever since. In an interview given a few years ago, Boissenot volunteered that in addition to being impressed by the young wine, he was also impressed with what he termed de Vink’s “humble determination,” which seems like an accurate and fair description for this ambitious but extremely likable young man now reaching middle age.

From US Marine, to MBA, to cellar rat

Rutger de Vink did not come from a wine background, but he did come from an economically advantaged one, and one that prized initiative. His father, Lodewijk JR de Vink, came to the United States for his graduate degrees and rose in the corporate world of pharmaceuticals to become chairman and CEO at Warner Lambert before engineering its sale to Pfizer in 2000.

Young Rutger attended an international school in Switzerland before the family moved to the US when he was 15. He graduated from Colgate University and subsequently spent eight years in the US Marines, seeing service in Somalia, before returning to academia to get an MBA from the Kellogg School of Management at the University of Chicago. After a brief stint in venture capital in Washington, DC, de Vink decided he wanted a more outdoors and physical life and settled on wine growing.

During the early 2000s, de Vink took the time to learn the business hands-on, working several harvests in the US and Europe. The first was at Linden Vineyards with Jim Law, now his neighbor, who had established his own reputation for elegant and long-aging Bordeaux blends made in Virginia. De Vink and Grainer later returned to Linden to produce the first two vintages of RdV while waiting for the winery to be constructed. Next, de Vink ventured to Sonoma County in California, a place high on his list of potential winery sites, working with David Ramey at Ramey’s eponymous winery before going abroad for harvests in Bordeaux at Cheval Blanc on the Right Bank and Lagrange on the Left.

Ramey, who himself apprenticed at an early age in Bordeaux with the Moueix family, speaks fondly of de Vink and notes the younger man holds the speed record for cleaning out a red-wine tank during harvest. Ramey also introduced de Vink to soil scientist Daniel Roberts, who help searched for and appraise a vineyard site. Once de Vink decided on the challenge of making a cru in Virginia, he looked for a property that was well drained, since Virginia has about 44in (1,000mm) of annual rainfall. “In California, they have to deal with water deficit,” de Vink says. “Here, we deal with water excess, though it often comes in thunderstorms, which drain quickly.”

De Vink tells the creation story of how he stumbled across his dream location while driving on a back road and came across a wandering flock of sheep, an encounter that one might more naturally expect in Spain or France. He alerted a young woman at the farm while taking time to quickly survey the property. “I returned the next week with flowers,” de Vink says. “When I inquired about the property, the farmer warned me the soil was too rocky to grow anything,” de Vink remembers. “Besides, the property wasn’t for sale.” But after a long courtship with the farm family and consulting on terroir with Roberts, de Vink at last had his ideal setting.

De Vink again relied on his network in pricing the first RdV vintage waiting to be released. “When we were tasting it with friends in Bordeaux, they said, ‘You have to charge over $100 a bottle,’” de Vink says, “but we finally decided on $88.” Similarly, there was the question, while de Vink was still working with the blueprints for the new winery, of whether he should create an impressive space for entertaining guests. “Mary Maher, who was vineyard manager at Harlan [winery in California], told us, ‘You have to have a place in your winery to receive guests.’” So, de Vink did and also eventually opened the winery to guests on a selective basis.

Recognition and validation

Today, visitors are welcomed with a flute of Champagne and given the option of a three-vintage tasting of RdV or a comparative tasting with French and American counterparts, says RdV’s hospitality director Karl Kuhn. At the time of my visit, that meant tasting an RdV vintage alongside a Moueix 2018 Ulysses from Napa Valley and a 2019 Château Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande.

The winery building itself is Y-shaped and on two levels, with natural light reaching down into the center of the cellar. Adjustments had to be made when exploration for tunneling found solid granite underlying about 18in (46cm) of topsoil. When de Vink and Grainer lead an exploration of the underground, it ended at an open facing of solid rock. “It shows how rainwater runs off the hillside,” de Vink says, examining the surface. “By mid-June, this wall is dry.” We walk by a small laboratory, but its usage is limited to essential needs. “Extraction and blending are the most important things,” Grainer says, “and no lab can tell you how to do that.”

Now, 12 vintages in, de Vink is concentrating on building on the success he has had so far. His guideposts for sustaining his goal of being an American cru, he says, are “continued validation from Eric and being recognized as equals with your peers,” whom he sees as clearly being top producers, ones primarily in California and Bordeaux. After a moment, he adds, “We want to be the Screaming Eagle of the East Coast.”

There is some thought of producing a white wine—after all, a few of the top Left Bank châteaux produce one—and an acre (0.5ha) of vines has been planted to an unusual mix of Albariño, Petit Manseng, and Semillon. But de Vink indicates that doing this was primarily a concession to members of his team, and that any white wine made will be for personal use.

And de Vink is learning—despite all his inquiring restlessness—to enjoy the moment and reflect on the achievements of the past two decades. He and his wife Jenny Marie, who helps with the business side, have settled into the property and their new home, one designed by noted architect Tom Kundig and constructed on a wooded knoll above the vines. Their four children—“blended family,” since both have previous marriages—are all young adults and away from home.

Additionally, with all the acclaim he has received and the august company he keeps in the wine and food world, one could either view de Vink’s vision of a world-recognized Virginia cru somewhat skeptically as an interesting work but one still in progress, or optimistically as an accomplished reality, in the process of being solidified—a glass still half-full or one waiting to be topped up. Fittingly, the illustration on the RdV label is of three birds perched in a row, two looking to the future, but the third, with its head turned, surveying the past.

Following a lunch at the winery of English pea soup with scallops, then lamb chops with fresh asparagus, along with a couple more vintages of RdV and a bottle or two of Meursault, de Vink relaxes enough to say, “When I started out, this is what I had hoped for. It’s been surreal.”

But as he says it, there remains a faraway look in his eyes.