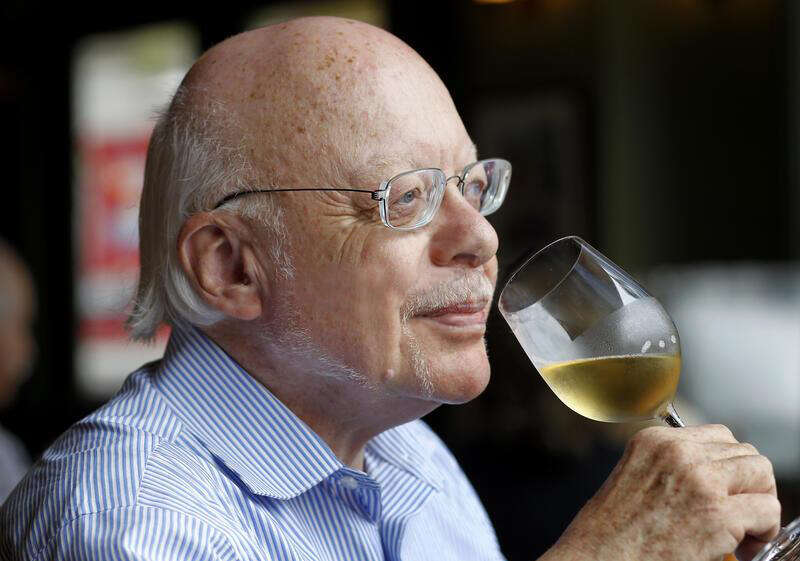

Among the cognoscenti to have been inspired by the man and his wines, William Kelley pays tribute to Terry Leighton, the self-effacing genius behind Kalin Cellars, California’s most idiosyncratic winery.

With the passing of Terry Leighton of Kalin Cellars at the age of 78, the state of California has lost one of its most pioneering and original winemakers. Terry and Frances, his wife of 51 years who predeceased him, were professors of microbiology who dared to reimagine the parameters of the possible for Californian wine; even if that meant relinquishing the fame and fortune that the success of their early releases promised. Yet as among the first to barrel-ferment white wines in California, and as pioneers of cool-climate Sonoma County vineyards such as Charles Heintz, Lorenzo, and Dutton Ranch that are today almost household names for North American wine lovers, their influence runs far deeper than many know.

Science at the service of art

For the Leightons, lost causes were an irresistible attraction, whether that was the old-vine Semillon growing in Livermore Valley’s deep gravel soils, a relic of 19th-century California wine pioneer Charles Wetmore; or the ambition to release wines only when ready to drink, with more than a decade of age on cork. Always eager to confound doubters, Terry and Frances even acquired two small parcels in humble Côte de Beaune lieux-dits in 1995, long before the recent explosion of all things Burgundian. Kalin Cellars was, in short, as the inaugural issue of The World of Fine Wine observed, “never about the money” (WFW 1, 2004, p.100.); and the Leightons’ uncompromising commitment to excellence meant that they were more interested in the one wine lover who understood 20-year-old Chardonnay than the 30 who didn’t.

“Fine wine is a journey, not a destination,” was one of Terry’s many thought-provoking maxims, and the Leightons journey began in the 1970s, when they were invited to consult in their capacity as microbiologists for the JW Morris Port Works in Emeryville (where Dominique Lafon would intern a few years later). Winemaking piqued their interest, and Kalin Cellars was born shortly afterwards in 1975. From the beginning, reds were vinified in open-top Redwood vats and basket-pressed, and whites fermented in barrel, using methods modeled on artisanal practise in the European regions whose wines had captured the Leightons’ hearts as young graduate students.

This commitment to a decidedly Old-World approach, which they juxtaposed to more commercial “Fast Wine,” was enduring, and while Terry and Frances both resolutely identified as scientists, science was firmly at the service of art; the Leightons’ aspiration was to better understand, and better control, time-honored practices, rather than any attempt to reinvent the wheel. Nothing was off limits, whether that was white wine fermenting for over a year in barrel, or four-year élevage for Cabernet Sauvignon. Indeed, one of the many glorious improbabilities that defined Kalin Cellars was that two North American children of the 1960s, Terry resolutely sporting a Fu Manchu moustache (as a young man, his band opened for The Doors), should have become unlikely guardians of the temple of traditional French winemaking.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the acclaim with which the Kalin Cellars wines were received combined with the Leightons’ insights as microbiologists led to a very discreet career in consulting. During this period, Terry and Frances advised well-known estates in Burgundy and Bordeaux that were experiencing problems with malolactic stability and stuck fermentations. It was during a tasting in Puligny-Montrachet, Terry recounted, that he became convinced of the importance of fully complete alcoholic and malolactic fermentation, as a way to avoid filtering for stability. Work in Pomerol also inspired a characteristically Kalin one-off bottling of Merlot in 1981. In this period, the Leightons also ran a biotechnology company, propagating and selling malolactic cultures to the likes of Williams-Selyem’s Burt Williams well before the existence of the dried malolactic isolates that are so readily available today.

Above and beyond

In the 1980s, Kalin Cellars throve, patronized by a celebrity clientele and served by the glass at the likes of Wolfgang Puck’s chic Michelin-starred Spago in Los Angeles. Kalin won lavish praise from Robert Parker, then in his heyday, who dubbed Terry an “eccentric genius” and lauded his Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Semillon, and Sauvignon Blanc as among the best produced in North America. “These wines approximate what Chambertin tastes like when made by the likes of Lalou Bize-Leroy,” raved Parker, suggesting that “anyone who is familiar with the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti’s magnificent 1980 La Tâche might want to try a bottle of Kalin’s Cuvee DD for comparison.”

North American wine culture was changing, however. In his reviews, Parker had observed that while many Californian Chardonnays tended to evolve rapidly, Kalin Cellars’ were only beginning to open up with four or five years in bottle. Yet an end to tax exemptions for winery inventory combined with an influx of new consumers who hadn’t grown up in a traditional wine culture meant that wines were being drunk younger and younger. Rather than change their approach to deliver more youthfully accessible wines, the Leightons’ solution to the problem was typically fundamentalist: they simply began systematically aging their wines before release.

While that won them friends with consumers passionate about mature wines, and while aged bottles of Kalin opened many an eye to the true potential of California wine, this late-release policy also did something to marginalize the winery in a market increasingly oriented toward critical reviews of “the latest vintage.” Terry, of course, was just fine with that, a mentality exemplified by his series of so-called “stealth cuvées,” wines from particularly good selections of vineyards and grapes, often named in homage to important individuals in the Kalin pantheon such as Willy Joslin, the viticulturist at Wente Vineyards who had done so much to preserve the Livermore Valley’s old vines. These cuvées, which saw extended élevage and even later release, were “named after the aircraft [i.e. the Stealth Bomber],” Terry liked to say: “If you don’t see them coming you won’t see them going.”

In their last declining years, the pace of Kalin releases slowed and then stopped, but admirers of California’s most idiosyncratic winery will be pleased to know that several hitherto unsold vintages are still waiting in the wings. They will be a fitting tribute to a couple who certainly lived up to their credo: Never produce a wine with less character than yourself.