Over the past 20 years, The World of Fine Wine has published a series of in-depth pieces looking at some of the world’s most exciting and distinctive terroirs in our “Genius Loci” series. This summer we are taking the opportunity to publish some of the best of the series online for the first time, with this week’s contribution from WFW69 in September 2020 taking a fresh look at Liebfraumilch wine, a historic German name weighed down by a terrible reputation.

Fine dry Riesling is once again being produced from the Liebfrauenstift vineyard, says Anne Krebiehl MW. But can this historic Rheinhessen site ever break the link with a wine that stands for overproduction and greed?

Few wines come with as much baggage as Liebfraumilch. The name encapsulates everything that went wrong with a wine country. It stands as a salutary tale of what happens when greed is allowed to traduce the idea of origin and authenticity beyond all recognition—aided and abetted by law. But the name also reveals a long history spanning tumultuous centuries that now, finally, comes full circle. Wilhelm Steifensand, a direct descendant of the Valckenbergs, the family that first bought the venerable ecclesiastic Liebfrauen vineyards at auction in 1808 and has owned them ever since, intends to return the wine to its historic glory by making fine, dry Riesling from grapes grown exclusively in the Liebfrauenstift vineyards—as it was in the days of its early and undoubted fame.

It all began in a churchyard, namely in the vineyards surrounding the Liebfrauenkirche, the Church of Our Dear Lady, in Worms, Rheinhessen, Germany. The wine from these vineyards came to be known as Liebfraumilch/Liebfrauenmilch, or “Our Dear Lady’s Milk.” If such a figure of speech may seem outlandish today, readers need only look up the numerous depictions of the lactation of St Bernhard, a popular and enduring legend in pre-Enlightenment Europe. The name Liebfraumilch was fitting for Worms.

While its status as the oldest city in Germany is contested, via Celtic settlement and Roman town it became a center of early Christianity, the seat of bishops from the 6th century onward, as well as a trade hub—not to mention the initial setting of the 13th-century Nibelungenlied epic. With its strategic position right on the River Rhine, conflict was never far; indeed, war spelled almost complete destruction twice over, once in 1689 and again in 1945. Piecing the Liebfraumilch story together in its entirely is thus impossible—too many records are lost—but parts of it can be reconstructed, not least via surviving research predating the bombing raids on Worms in 1945, which destroyed most of the archives. Built on a site of early Christian worship, construction of the Liebfrauenkirche on the northeastern outskirts of the city began in 1276 and was complete by 1468.1

Like most churches at the time, it was endowed with vineyards. Construction of the cloister began in 1467, and the first pilgrimage to the site is documented for 1478. Pilgrims would have been given this local wine, which is likely to have contributed to its early reputation. They came to worship a picture of the Virgin Mary dating from 1260 within the church—rather than the now famous Schutzmantelmadonna, a 1460s sculpture of the Madonna of Mercy with her sheltering cloak, hewn from sandstone and always located out in the church vineyards.2 Liebfrauenmilch’s first registered brand name “Madonna” is down to her—but more of that later. From 1630 onward, Capuchin monks tended the vineyards and made the wine, which was both sacramental and alimentary.3

A report filed by a French traveler in 1687 is thought to be the oldest surviving mention of the “Milk of Our Dear Lady” name, but the usage suggests it is far older. Noting both vines and wine in Worms, he writes, “They highly prize this Wine and they have a Proverb that it is sweeter than the Virgins Milk [sic]. The City presents it to Persons of Quality as they pass by.”4 By the time the Frenchman visited, Liebfraumilch was thus locally famous, notwithstanding the ongoing ravages and military occupations of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) that the city had endured. But worse was to come. The entire city was burned to the ground by Louis XIV’s troops in 1689 during the War of the Palatinate Succession (1688–97). The regret is still palpable in a record from 1927: “Destroyed is the splendour of the medieval town with its twelve towering gates, its sixty rampart towers, its fifty churches, its town, arsenal…”5

The fires caused the church’s vaulted ceiling and a part of its tower to collapse and destroyed outbuildings.6 Rather than rebuilding the entire cloister, more land was planted to vines—further evidence of the wine’s significance to Worms. A surviving Festschrift from the 1930s, drawing on records that are now destroyed, gives detail on subterranean heating channels, fired from nearby pits, that warmed the vineyard soil.7 This huge and unusual effort perfectly illustrates the importance of this wine to the Stiftsherren, or canons, of the Liebfrauenstift church. Each barrel and bottle was sealed with the insignia of the Stift and despatched with a certificate of origin to document authenticity and provenance.8 The term Liebfrauenmilch crops up in numerous diocesan and municipal tax and sales records throughout the 18th century—by then, the name had been coined, was in constant use, and was known beyond its region.9

But European conflict raged on: Napoleon’s troops first occupied and then annexed the German territories on the left bank of the Rhine. The bishopric of Worms became part of the French Département de Mont-Tonnere in 1797. Bit by bit, Napoleon dissolved the monasteries and auctioned off ecclesiastical land, prompting cataclysmic societal change. The Capuchin monks had to leave when their monastery was dissolved in 1802. By 1808, the vineyards were auctioned off, and the famous Liebfrauen vineyards came into private hands, after centuries of feudal ownership.10

Among the winning bidders was Peter Joseph Valckenberg (1764–1837), a Dutch merchant who had settled in Worms, where he founded a wine business in 1786.11 The vineyards he bought in that transaction have remained in the family’s hands ever since. Although it must be noted that other bidders were successful, too, buying other parcels of the original vineyards, it is the Valckenbergs who managed to cling on all this time and increase their holding. Wilhelm Steifensand, latest scion of this family that has run the still active Valckenberg business for more than 220 years and has made wine from the original Liebfrauen vineyards just as long, sold his stake in that concern in 2015 but retained the original vineyards and Liebfrauenstift estate. It was Peter Joseph Valckenberg’s son Wilhelm (1790–1847), traveling far and wide, who made Liebfraumilch’s international reputation.

A summary of the surviving records donated to the Worms archive notes a staccato of names and places to which he sold Liebfraumilch: “Charles Dickens, Baron Rothschild, bishop of Canterbury [sic]; leading inns in Copenhagen; 300 clients in Berlin; Sweden, Belgium, France, Spain, Portugal, Austria, Switzerland, Italy; Riga, St Petersburg, Odessa, Constantinople, Egypt, Malta, Singapore, New York, Cincinnati, Veracruz; Valparaiso.”12 Steifensand adds further color to the illustrious clientele, noting that the Prussian state archives reveal that even “der Alte Fritz,” Prussian King Friedrich II (1712–86), had Liebfraumilch in his cellar. Steifensand adds that it is just as likely that Martin Luther, summoned before the Reichstag in Worms in 1521,13 drank Liebfraumilch and notes that Valckenberg supplied numerous European royal courts by the mid-19th century.14

The wine town of Worms also presented German Chancellor Bismarck (1815–98) with a wine present on each round birthday, dedicated by its citizens to the statesman, and Steifensand says that this “always was Liebfraumilch from the Liebfrauenstift.”15 Liebfraumilch, famous and revered locally for centuries, thus attained national and international fame in the 19th century—at the same time as German Rieslings from the Rhine and Mosel became the most expensive and sought-after white wines in the world.

From precious specificity to lieblich cliché

Whether Liebfraumilch was initially made from Riesling is not known. Like elsewhere across Europe, provenance, not grape variety, was the deciding factor in naming wines. The medieval vineyards may well have been planted to field blends. Bronner’s famous compendium on German viticulture published in 1834, however, dedicates a separate chapter to the Liebfrauenstift and notes that by then “the vines consistently are Riesling, here and there some Traminer and Sylvaner is mixed in, but only on few parcels.”16

But why was the wine so prized? There were, after all, vineyards almost all along the Rhine, and only some of them were famous. Why was this wine singled out? One theory is the presence of red sandstone in the gravelly alluvial loam, which is down to the former location of the Pfrimm estuary, a delta of a Rhine tributary that carried fluvial deposits of the red sandstone of the Pfälzer Wald, enriching the alluvial gravels of this Rhine bank with more fertile soil. Another is the particular climatic conditions created by the walled vineyard and the protection from northerly winds afforded by the church. Then there also is the debris, ash, and rubble resulting from the sack of Worms in 1689.

Heiner Maleton, estate manager since 2017, makes a compelling case that the effect of this may not have been too dissimilar from the soil-improving aspects of biochar today. Whether this was just an alliterative habit or a real descriptor, Liebfraumilch was almost always described as being lieblich—a term that then denoted mild, graceful, smooth, or lovely but has come to be defined in German law—notably post-1971—as denoting a semi-sweet wine with 12–45g/l of residual sugar. This is not to say that Liebfraumilch then was sweet or even sweetish. Unless the wines were nobly sweet—that is, too sweet to ferment to dryness—they were dry. If there was unfermentable sugar at all, this would still have been in the feinherb or off-dry region. But that is a whole different subject. Suffice it to say that Liebfraumilch was prized for its mildness and gentleness at a time when a lot of wine was simply anemic and sour.

Genius Loci—Sierra de Gredos: The haunting beauty of a complicated terrain

The Valckenbergs thus owned a little goldmine of land with their original church vineyards with a wine that was fashionable and in demand, but they had no way of protecting the name. Soon Liebfraumilch was the name given to all wine grown “where the church spire casts its shade,”17 but Pfrommer notes in 1834 that this dictum “suffered endless modification” by various neighboring estates as “the further from the church, the lesser is the wine.”18 At least the estates using that name were in Worms. Officially, this remained the case. The catalog of the 1900 Paris World Exhibition notes that Liebfraumilch is “grown on a small area in Worms.”19 In reality, the name was widely used and misused. A source from 1844 states that “large quantities of Haardt [Pfalz] and other wines are christened with this popular name in northern Germany and the Netherlands. In France, the wine is also known under the name Lait de la Vierge and it enjoys a high and well-deserved reputation even in England. There is not a Briton that comes to the Rhine who fails to ask for Liebfraumilch.”20 Thus, demand was high, and merchants tried to satisfy it—using the name freely.

German law at that time did not offer any possibility to protect origin. The first wine law of the new Germany unified in 1871 was passed in 1892 and made no reference to wine origin at all.21 The wine law of 190922 dealt with provenance and origin but was fairly loose insofar that it permitted “to use the names of individual districts or vineyard sites that belong to more than one district to denote similar or equivalent produce of neighbouring or nearby districts or sites.”23 The German wine law thus positively encouraged lesser wines to ride on the coattails of more famous names. No wonder the Verband Deutscher Naturweinversteigerer, the Association of German Naturwein—that is, non-chaptalized, non-gallicized wines—Auctioneers founded in 1910 insisted on selling their pure, estate-bottled, and estate-grown wines from famous sites by auction only; this had been the done thing in the Rheingau since the 1840s and in the Mosel since the 1880s. They thus guaranteed authenticity and provenance.

When history books mention the stratospheric prices and world fame, they refer to the elite bottlings of Riesling sold at these auctions. Worms, however, was not the Rheingau, where aristocracy prevailed. The town was dominated by wine commissionaires and merchants, all of whom wanted to have their slice of the Liebfraumilch pie. So, what to do? In 1908, it became possible under German law to register trademarks, and the Valckenbergs thus registered Germany’s first ever Markenwein (trademarked wine), calling it “Madonna Liebfraumilch,” basing the name on the 15th-century sandstone Madonna in the church vineyards.24 Steifensand reports that the grapes for the branded wine were sourced in the Wonnegau, the hilly limestone subregion stretching from the northern outskirts of Worms in southern Rheinhessen. The house thus distinguished between its Madonna Liebfraumilch brand, initially probably Riesling according to Steifensand, and its Liebfrauenstift-Kirchenstück Riesling from the church vineyards.

Notwithstanding the already slippery German wine law, Liebfraumilch was treated to an even more special status in 1910. Far removed from the elite bottlings of Rheingau and Mosel, Liebfraumilch enjoyed such fame and popularity that the Chamber of Commerce of Worms and the Association of Rheinhessian Wine Merchants declared on April 29, 1910, that since there was no site in Worms called Liebfraumilch—only sites named “Liebfrauenbuckel,” “Liebfrauenreich,” and “Liebfrauenstift”—the Liebfraumilch name was to be considered a Phantasiename and could thus be widely used.25 Alfred Langenbach was a Jewish wine merchant from Worms forced to flee Nazi Germany. He found refuge in the UK, where he became an authority on German wine, authoring two books on the subject. He notes that this resolution “at the time also found unanimous approval and confirmation from all German Wine Trade Associations, and has since been referred to in court decisions.”26

This, in effect, is where the downfall began. Langenbach gives the 1910 wording in detail: “In answer to an inquiry by the Association of Rhenish-Hessian wine merchants, and after hearing interested parties, and repeatedly explaining the question in great detail, the Chamber of Commerce finds that the commercial view of the significance of the name Liebfraumilch applied to wine as follows: It must unreservedly be acknowledged that the description Liebfraumilch should, in itself, be regarded as an imaginary name, and even though this designation originated from an association with the vineyards of the Liebfrauenstift in Worms, it has become the accepted view of the Trade, that—in consequence of the many decades during which reputable traders have made a somewhat free and unrestricted use of the name, and of the resultant wide distribution of this mark [sic; this should read ‘brand’] as a renowned wine of quality—the imaginary name Liebfraumilch applies exclusively to Rhine wines of good quality and delightful [his translation of lieblich] character.”27

He comments further that “this resolution has ever since been accepted as a basic whenever court decisions were given. The extent in the use of ‘Rhine wines’ remains however still an open question. Efforts of the controlling inspectors to restrict the designation to Rheinhessen wines only have been strongly opposed by the Palatinate [Pfalz] and it cannot be denied that historically the connection of the former Free Reichsstadt [Imperial] City of Worms was quite as strong with the Palatinate as with Rheinhessen into which it was incorporated only in 1815.” Even writing in 1962, his frustration at this resolution passed in 1910 is still evident and justified. Rightly so, since Liebfraumilch’s popularity in its traduced form was still gaining popularity.

Phenomenal popularity and commercial success of Liebfraumilch

The figures tell their own story. The house of H Sichel Söhne in Mainz—another Jewish family caught in horrendous Nazi persecution—had registered its own Liebfraumilch trademark Blue Nun in 1923 with the 1921 vintage, which became a huge success, 1921 having been an outstanding vintage.28 Peter MF Sichel dedicates a chapter of his fascinating autobiography to Liebfraumilch and illustrates honestly what Liebfraumilch actually became after World War II and before it was defined by law in 1971.29 Sichel calls this definition “strict regulation,” when it certainly wasn’t—but here is the pre-1971 view of the trade in Sichel’s words: “Liebfraumilch was more or less a generic appellation for Rhine wine. Bottlers used and blended wine from different Rhine regions, which made it easier to blend them consistently from year to year.”30

The importance of Liebfraumilch to the trade is also evident in numerous treaties the Federal Republic struck with other European states agreeing the mutual recognition of protected designations of origin. The 1961 treaty with France mentions Liebfraumilch as “regional designation of origin” amid Dresdner Stollen, Nürnberger Bratwurst, Bresse chicken, Puy lentils, and various German and French wine appellations. As the Federal Republic passed its new wine law in 1971, the Federal State of Rheinland-Pfalz, which incorporates the wine regions Pfalz, Rheinhessen Mosel, Nahe, Mittelrhein, and Ahr, defined Liebfraumilch thus: “A Qualitätswein made from white grapes may be called Liebfraumilch when the grapes were sourced exclusively in the regions of Nahe, Rheinhessen, and Rheinpfalz with a minimum must weight of 60º Oechsle and no grape variety named on the label. The wine has to be lieblich in character, and must predominantly be made from the varieties Riesling, Silvaner, or Müller-Thurgau and bear the varietal character of these grapes. The ratio between alcohol and residual sugar cannot be less than 3:1, for Riesling 2.5:1.”31

This law cannot possibly be called “strict” and gives an excellent clue as to what Liebfraumilch used to be made from and what it tasted like. The term Qualitätswein, an oxymoron in this case, was of course defined by law and permitted chaptalization. With a minimum must weight of 60º Oechsle, which equals just 7.65% potential alcohol by volume, this tells the tale of a pre-climate-change Germany with tons and tons of underripe grapes that could be made into passable plonk by a good, legally mandated dollop of sugar. In fairness, the law also allows Liebfraumilch to be made from 100 percent Riesling with an off-dry character—a delightful style indeed. But the law says just as much about Germany’s post-1945 conviction that agriculture could be rationalized and modernized with the help of modern technology, that produce could be commoditized and manipulated to suit the market—or at least the convictions of large négociants and co-ops who were good at lobbying and politicians who wanted to be re-elected. Plus ça change…

But who am I to sneer? Liebfraumilch became a huge success in export markets. A Guardian article from 1986 profiling an 80-year-old Walter Sichel in his London offices in the Adelphi notes a statistic of 24 million bottles of Sichel’s Blue Nun sold annually to 91 countries.32 The UK and US were the leading markets for the wine that turned a whole new demographic onto the joys of Bacchus throughout the 1960s, ’70s, and early ’80s. The era’s corny TV advertisements can still be watched on YouTube.

Again, Peter Sichel’s words say it all: “Due to the large area where the designation Liebfraumilch was permitted, we had a plentiful supply of base wines at more or less steady pricing. Blue Nun always carried a vintage year, something considered essential according to consumer research.”33

That research, Sichel says, also revealed that pure Riesling did not do as well as Riesling blended with Müller-Thurgau and Silvaner—a boon for merchants, since those varieties were cheaper. Of course, another region also wanted in on the act, and thus the federal wine law, rather than just the Rheinland-Pfalz wine law, had a new paragraph inserted in 1983 that added the Rheingau to the already existing source regions of Nahe, Rheinhessen, and Rheinpfalz.34 It also mandated that the wine had to be sweeter than halbtrocken—that is, it had to have more than 12g/l of residual sugar. Liebfraumilch was redefined again in federal law in 1995, stating the same four regions of origin and mandating that at least 70 percent of the wine had to be Riesling, Silvaner, Müller-Thurgau, or Kerner and the sweetness had to be in the lieblich range—between 12g/l and 45g/l of residual sugar.35 This, with a minor change concerning labeling in 2009, is still the legal definition of Liebfraumilch today.

Whatever became of Liebfraumilch, it is remarkable that federal law to this day contains a definition for a name, albeit traduced, that was coined in a feudal church state in the Middle Ages. This is testament to the power of its name, even if that name is something of a laughing stock today. The ever looser definition, from 1910 onward, almost managed to destroy the reputation not only of German wine but that of Riesling. We still live with the damage it wrought. And yes, you can buy a bottle of Valckenberg’s current vintage of Madonna Liebfraumilch for less than $10 in the US and various generic Liebfraumilch wines for less than £5 in the UK.

Recovering lost luster and restoring pride in place

It was a courageous move, then, by Wilhelm Steifensand to resurrect the original Liebfraumilch—even if he cannot call it that. That the vineyards are special is evident when you get there. Now the vineyards are surrounded by residential streets, the western side is bounded by the B9 highway, and just 300 yards beyond that is the Rhine. The spires of the Liebfrauenkirche are set sharply against the blue sky. That Steinfensand has picked the right man to kiss this sleeping beauty awake is also evident. Heiner Maleton, manager and winemaker at the estate, is clearly in love with these ancient vineyards, aware of their history.

“It can be quite edifying to work here,” he says, “where the sweat of 400 years and more of toil has moistened the soil.” As he walks through the vineyards, lush and green, surrounded by elder bushes and acacia, overgrown with rampant ivy and honeysuckle, with the traffic of Worms roaring past behind this tiny idyll, Maleton says, “I always think of this as urban farming.”

We stomp through the grass as he points out the different parcels. Directly in front of the spires to the west of the church are Stiftsmitte and, for now still unplanted, Kirchenschlüssel (“Church Key”). The church itself stands on a slight knoll. The adjoining vineyards to the north of the church are known as Liebfrauenbuckel. Six rows of vines also sit on higher ground along the old ramparts on the north side of the church, known as Auf der Mauer (“On the Wall”). The vines on lower ground, below the embankment of the knoll, are on a parcel called Graben (“Ditch”), where the soil is lighter and sandier. The parcel at the back of the church, on the east side toward the Rhine, is called Klostergarten; the parcel to the south of the church is called Kreuzgang (“Cloister”).

Before the 1971 wine law brutally weeded out thousands of site names, the parcels were still individually named and used on labels: Liebfrauenstift-Kreuzgang, –Kapitelhaus, –Klostergarten, –Kirchenschlüssel, –Madonnenbuckel, and more. Steifensand and Maleton are happy to resurrect the names. The Liebfrauenstift vineyards cover 13ha (32 acres) in total. Some 1.5ha (3.7 acres) are owned by three other estates, one being Weingut Gutzler in Gundheim, Rheinhessen, which has made a splendid Liebfrauenstück Riesling Grosses Gewächs for years, showing how warm the site is, rich in tropical overtones. The VDP has classified part of the site as Grosse Lage—recognizing not only the special soil of this (for Germany) unusually flat site but also its historic significance. The remaining 11.5ha (28.5 acres) are owned by Weingut Liebfrauenstift, of which 6ha (15 acres) are currently farmed, while the rest is still leased out to another farmer who is contractually forbidden to make a wine bearing the Liebfrauenstift name. He currently sells the grapes to a co-op.

As the current 6ha are in conversion to organic certification, Maleton wants to focus on these before adding any further uncertified land to the estate, making the effects of his farming methods felt, establishing the wines and the brand, before taking on more of the estate’s land. He arrived in December 2017 and quickly had to come to terms with the heatwave vintage of 2018—a challenge in what is renowned as a warm vineyard anyway. Harvest started on August 3, 2018, and the key to his first vintage at the estate was a staggered harvest. The first, golden berries were harvested just as they ripened; grapes that weren’t golden were left on the vine. Maleton explains that two wines are made at the estate: a simpler Stiftswein, and the Liebfrauenstift-Kirchenstück wine—both from parcels surrounding the church but “one is more than twice the price of the other.” Making these two wines distinctive enough, and selecting the best parcels for each of them, was his chief challenge in the hot, dry and unusual vintage of 2018.

By summer 2019, he was a lot more comfortable in his skin, his gentle farming methods already having an effect. Maleton likes tasting the grapes from the different parcels in order to make his harvesting choices and to decide for which of the two wines they will be destined. The grapes in the Liebfrauenbuckel parcel, he says, tasted no different, “but in the last third of fermentation they clearly came through, demonstrating that the best grapes really grow in the immediate vicinity of the church.”

Throughout all the years from 1808, when the Valckenbergs first owned some of the vineyards, until Steifensand sold his stake and retained the Liebfrauenstift estate in 2015, they never stopped making a Kirchenstück Riesling from these vineyards around the church. But Maleton suspects his predecessors worked to the same “recipe” year in year out; they used to use the Stiftsmitte and Kreuzgang parcels, pressed, settled with the help of enzymes, used cultured yeast and exact fermentation temperatures—everything was tightly controlled. Maleton, who is unusually alive to all his senses, talking vividly about the sounds of the soil during tilling, the smell of the vines at pruning, has a more intuitive approach. Some batches are whole-bunch-pressed very gently, as though he were making sparkling wine, he says. Other batches are crushed and left to macerate for 18 to 24 hours. Smaller batches are fermented as whole berries, gently destemmed by hand.

“Each of these took a different route. You look at the grapes and they tell you,” Maleton says. His aspiration for this warm, urban vineyard is, above all else, elegance. He aims for a bone-dry wine, without malolactic fermentation, made from “ripe but not overripe grapes.” The 2018 Liebfrauenstift-Kirchenstück Riesling we tasted together in August 2019 was golden and clocked up 12.5% ABV. The nose was initially of peach and lemon with a savory undertow of crushed yarrow. The palate was also a picture of peach but here the lemon zest had turned to tangerine peel; slight tropical overtones played while a pleasantly pithy edge was a counterbalance. This is one of those Rieslings that will turn into pure balm with age.

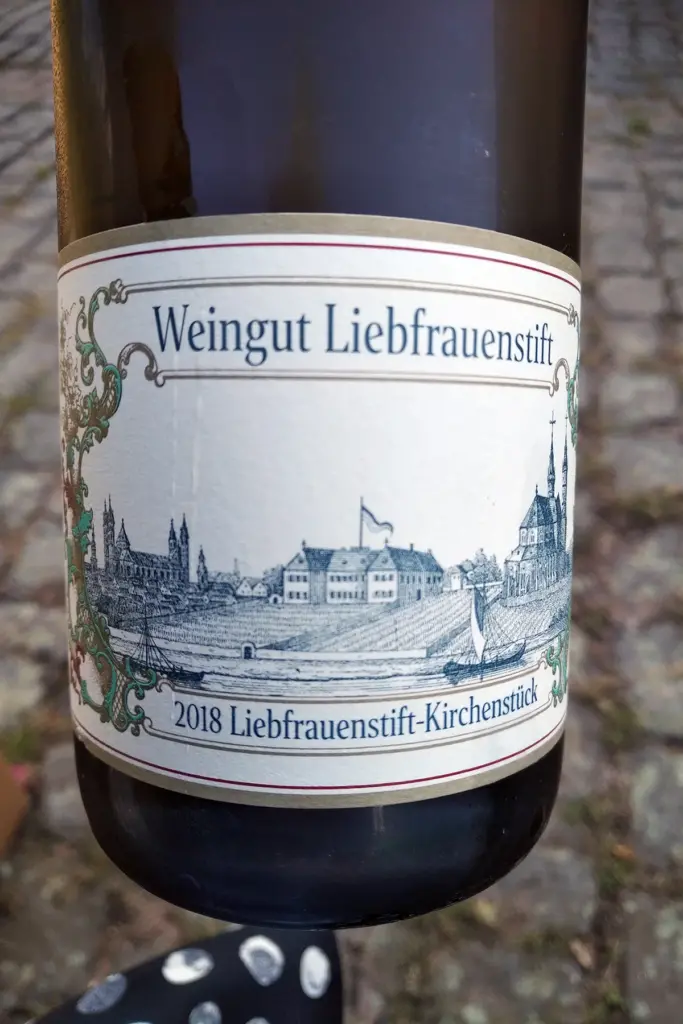

It will be fascinating to see what Maleton does over the coming years. The historic 19th-century label, showing Worms Cathedral in the distance, the Liebfrauenkirche, and the vineyards as seen from the river, has been revived (see above). The magic of the real Liebfraumilch has, too, as the placid, ancient face of the Madonna looks on and lends her blessing. “We want to return the reputation and place that this site once had in the wine world,” Steifensand says. He is well on his way.

Notes

1. liebfrauen-worms.de/stiftung/kirche/zeittafel.php

2. Correspondence with Harald Unselt, Liebfrauenstiuftung, Worms, October 29, 2019.

3. liebfrauen-worms.de/stiftung/kirche/zeittafel.php

4. François Maximilien Misson, Letter VIII, A New Voyage to Italy, Vol. 1 (R Bentley, London; 1695), p.55.

5. Hessischer Weinbauverband, Die Rheinweine Hessens (Philipp von Zabern GmbH, Mainz; 1927), p.231.

6. liebfrauen-worms.de/stiftung/kirche/zeittafel.php

7. Friedrich M Illert, Liebfraumilch: Aus der Geschichte eines Berühmten Weines (Erich Norberg, Worms; 1961). Almost all records for Liebfraumilch were lost in the Allied air raids on Worms in 1945 in which the Valckenberghof was destroyed. While barely any original records survived, a Festschrift published in 1936 to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Valckenberg contains valuable historic detail, which furnishes most of the history contained in the 1961 publication.

8. Illert, Liebfraumilch.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. valckenberg.com/en/people

12. Stadtarchiv Worms, Weinhandelshaus/Familie PJ Valckenberg GmbH (Dep.) (Bestand); deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/item/BDJG2TONDESHIVIGPFHWW74FSI5RNEUS

13. Reichstag = Imperial Diet, the deliberative body of the Holy Roman Empire. Martin Luther was summoned to defend his publications and refused to refute them, which prompted the Edict of Worms in the name of Emperor Charles V.

14. Correspondence with Wilhelm Steifensand, April 18, 2019.

15. Idem.

16. Johann Philipp Bronner, Der Weinbau in Süd-Deutschland, Zweites Heft (CF Winter, Heidelberg; 1834), p.24.

17. Ibid, p.20.

18. Idem.

19. Otto Witt, Weltausstellung in Paris, Amtlicher Katalog des Deutschen Reiches (Berlin; 1900), p.99.

20. Illert, Liebfraumilch, p.24.

21. Gesetz, Betreffend den Verkehr mit Wein, Weinhaltigen und Weinähnlichen Getränken, dated April 20, 1892; Deutsches Reichsgesetzblatt Band 1892, No.27, pp.597–600.

22. Weingesetz, dated April 7, 1909; Deutsches Reichsgesetzblatt Band 1909, No.20, pp.393–402.

23. Weingesetz, dated April 7, 1909, Deutsches Reichsgesetzblatt Band 1909,

No.20, pp.393–402; see especially paragraph 6 for “gelichartig und gleichwertig“ and “benachbart und nahegelegen.”

24. deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/item/BDJG2TONDESHIVIGPFHWW

74FSI5RNEUS

25. Hugo Holthöfer, Deutsche Gesetzgebung über Wein, from Handbuch der Lebensmittelchemie, Siebenter Band Alkoholische Genussmittel (Verlag von Julius Springer, Berlin; 1938), p.475.

26. Alfred Langenbach, German Vines and Wines (Vista Books, London; 1962), p.130.

27. Ibid, pp.130–31. NB: Langenbach’s translation of the original German text.

28. Some sources date the registration to 1929, most others to 1923.

29. Peter MF Sichel, The Secrets of My Life: Vintner, Prisoner, Soldier, Spy (Archway Publishing, Bloomington; 2016).

30. Ibid, p.329.

31. Bundesgesetzblatt, Jahrgang 1961, Teil II, Gesetz zu dem Abkommen von 8 März 1960 zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Französischen Republik über den Schutz von Herkunftsangaben, Unrsprungsbezeichnungen und anderen geographischen Bezeichnungen vom 21 Januar 1960.

32. Aileen Hall, “The Nun in a Blue Habit with Something to Smile About,” The Guardian (London), January 31, 1986.

33. Sichel, Secrets of My Life, p.332.

34. Bundesgesetzblatt, Jahrgang 1983, Teil II, Fünfte Verordnung zur Änderung der Wein-Verordnung vom 4 August 1983.

35. Bundesgesetzblatt, Jahrgang 1995, Teil I, Verordnung zur Durchführung des Weingesetzes vom 9 Mai 1995 .