As the word suggests, complexity is a complicated issue—but in terms of importance, it comes second to almost everything else in a wine.

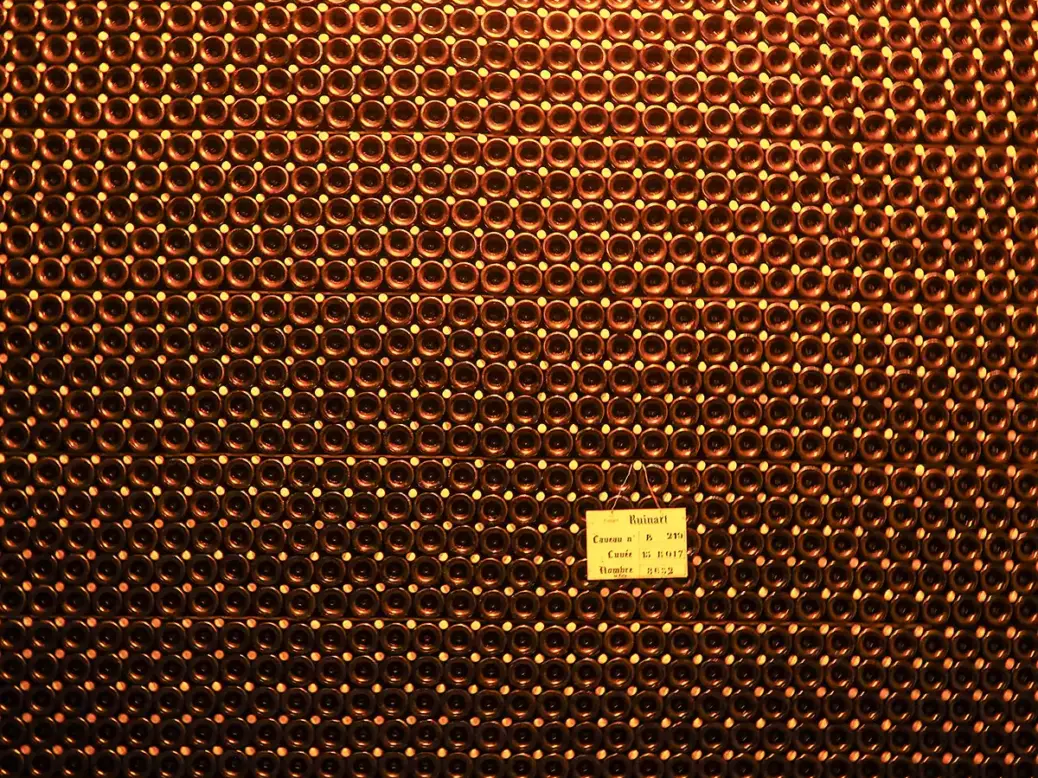

There are six primary categories of complexity in a traditional-method sparkling wine: the first fermentation, reserve wines, the second fermentation, yeast-aging, pre-disgorgement bottle aging, and post-disgorgement bottle aging. The first fermentation is faster than it is for a still wine. It provides varietal complexity, but its complexity is more potential than actual. Vins clairs can be fascinating, but they are seldom complex in any true sense. Reserve wines, on the other hand, provide an instant hit of complexity, the type and intensity depending on the age and proportion of the reserve wines and how they have been stored. The second fermentation takes much longer than the first, uses more varied metabolites and operates at a cooler temperature, resulting in a different complexity (more acetate-based).

Yeast-complexed aromas are the product of autolysis, a process that has such a delicate effect that it requires relatively neutral grapes. Even a classic Champagne grape like Pinot Noir can sometimes be too dominant for autolysis to reveal itself at the upper end of its cool-climate ripeness. At the opposite end of the varietal spectrum, terpene-laden aromatic grapes annihilate autolysis, and sparkling wines made from those varieties have to rely on either super-freshness or bottle-aged aromas. Autolysis usually starts a couple of months after the second fermentation has ceased and will have most effect over the following four to five years. Although autolysis is commonly active for up to ten years and has even been detected 80 years after the second fermentation, its effect on the aroma and flavor profile of a sparkling wine is minimal after five years. For a deeper dive into autolysis, see pp.26–27 of the 2019 edition of Christie’s World Encyclopedia of Champagne & Sparkling Wine.

Other than the direct effect of autolysis, pre-disgorgement bottle aging covers the entire period from the end of the second fermentation until disgorgement. This is when Maillard reactions can create precursors to future complex aromas from amino acids from autolysis reacting with sugar molecules. With all oxygen consumed by the second fermentation, all chemical and biochemical processes operate in almost completely anaerobic conditions. Almost completely, because the ingress of O2 molecules through the closure is so minuscule that it should really be called nanooxygenation rather than microoxygenation. The most important complex pre-disgorgement bottle-aged aroma is toast and derivatives, though toast can also come from barrels.

Against false goût anglais

When a sparkling wine is disgorged, it is not merely the matter of time on lees that determines its continuing quality but also whether it was disgorged when a window of opportunity presented itself (see “When to Disgorge?” WFW 45, 2014, p.74). Quite often and unsurprisingly, bottles of the same wine disgorged at different times will eventually develop in a similar fashion, but when one does not, it is almost certainly due to it having been disgorged when the window of opportunity had slammed shut.

Complexity of all sorts up to the point of disgorgement will be slow, whereas post-disgorgement complexity is faster, having been exposed to the air. Once shipped, a sparkling wine will be subject to multiple places of storage and the whims of the buyer, making development faster and less controlled. Even by the best-case scenario, including jetting prior to corking and the use of a super-efficient closure, such as Mytik Diam 10, and where the end product has been purchased by someone able to move it straight from the winery to a personal cellar possessing ideal storage conditions, the rate of development after disgorgement will always be quicker than before disgorgement. Even if the disgorged wine remains in its cellar of production, it will be quicker. Compare a commercially disgorged 30-year-old Champagne with exactly the same wine disgorged just 12 months earlier, and the contrast in the degree of toastiness and other complex aromas will be evident. That is the nature of the beast (mature Champagne). And while it is down to personal taste whether someone prefers pre-disgorgement or post-disgorgement aromas, pure science dictates that for both, the slower the development, the better. Mature Champagne is in the eye of the beholder, but dead Champagne is dead.

Occasionally, I encounter a Champenois who thinks that the goût anglais is a love of old Champagne. Mature, yes; but old, no. The times I have had a brown-colored liquid with very little fizz and a whiff of Sherry stuck under my nose… But that is the very antithesis of the goût anglais. Historically, the English have not loved the oldest Champagne; they have loved the oldest-freshest Champagne.

Anyone who has tasted a 100-year-old Champagne that still has a smidgeon of mousse, a golden color without a hint of brown, fabulous freshness, fruit, and finesse, with the purest notes of coconut, coffee, vanilla, and baking spices, but without any hint of acetaldehyde or volatile acid, will be as dismissive of the false goût anglais as I am. When this experience, though rare, is repeated over the decades, it is easy to appreciate how the glacially slow development of a truly monumental Champagne can achieve complexity and finesse in equal measure. Such wines will eventually die, of course, but so do great oaks.

Mind you, I am a dinosaur. There are people out there who expect recently launched Champagne to be oozing oxidation and aldehydes. Sorry, but if a premox white Burgundy is deemed faulty, why is it fine for Champagne, the most famous reductive wine in the world, to be prematurely oxidative?