Simon Field MW travels to Lyon to taste, with Ruinart chef de cave Frédéric Panaïotis, a bottle of venerable Champagne laid down by Paul Bocuse from his birth year, the other recently discovered bottles returning to Reims to form the cornerstone of the house’s new oenothèque cellar.

If Lyon is France’s gastronomic capital, then Restaurant Paul Bocuse is its high citadel. Located in a soi-disant Auberge in the village of Collonges-au-Mont-d’Or, 9 miles (15km) upstream from the city on the Saône, this magnificently idiosyncratic building is decorated, chalet-like, in bright raspberry and pistachio paintwork, its walls adorned with portraits of its eponymous founder and some of his signature dishes.

The world comes to Bocuse rather than vice versa, even if, five years after Paul’s death, it has lost the third Michelin star that had been held for a record 55 years. Inside, the art softens briefly to an arcade of black- and-white photography, the dramatis personae of the past 50 years, and then is transmogrified into a circus of mirrors, gilt, and marble. Dazzling copper implements bedeck the kitchen walls, most in daily use, and the artwork elsewhere is gloriously catholic, ranging in style from ur-Arcimboldo trompe l’oeil surreal to Botero bronze, from cartoon caricature to overtly hagiographic watercolor, all of it the toque of the town. An institution, then, playful, vulgar (some may say), and wonderfully at ease with itself.

The new cellar houses 13,000 bottles, Burgundy and the Rhône having overtaken Bordeaux only relatively recently. There is plenty of Champagne, too, much of it in larger format. M Bocuse was fond of collecting wines from his birth year of 1926, as we are about to find out, and tended, it seems, to store them somewhat randomly in what was at the time a magnificently labyrinthine series of rooms, some kept cool enough to earn the description of a wine cellar. “Monsieur Paul” died in 2018, joining the pantheon of greats such as Escoffier, Carême, and Vatel. Every other year, his potential successors compete for the Bocuse d’Or, an Oscar-like trophy awarded to the latest generation of master and mistress chefs. One can only presume (and hope) that he was able to celebrate over the years with a bottle or two of Ruinart from his birth year.

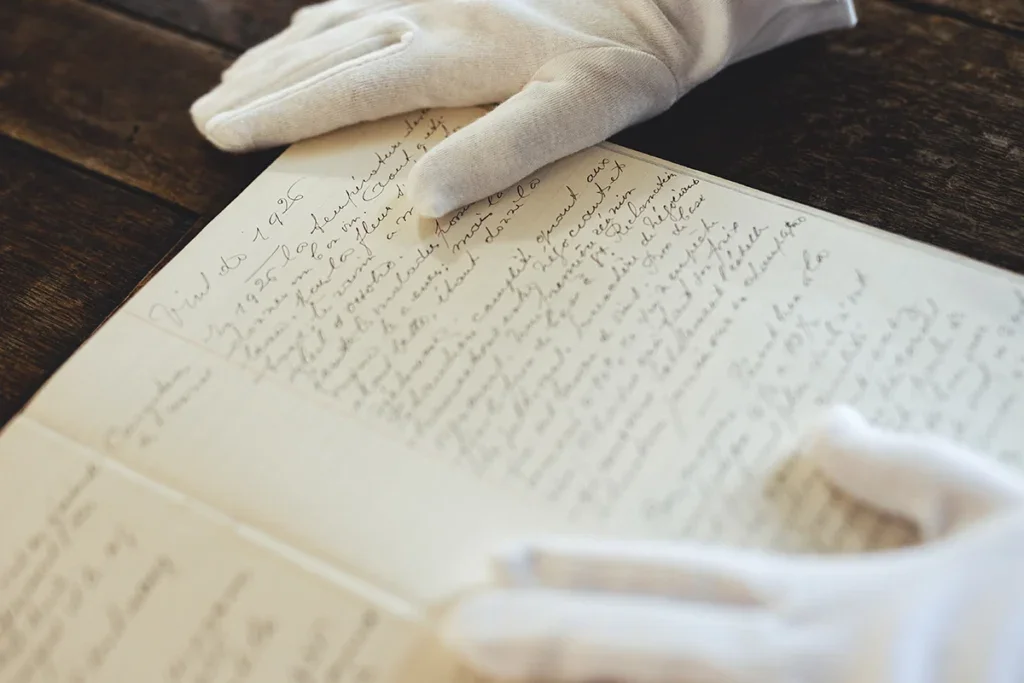

In November 2021, a post-renovation inventory was carried out by the recently appointed head sommelier Maxime Valéry, and it unearthed, inter alia, 18 bottles of 1926 Ruinart in a batch otherwise devoted to spirits, Chartreuse Tarragona and Cognacs among them. The 18 labels were virtually unscuffed, and the bottle levels were and are impressively high, even though they had not been kept in sealed cases. La Maison Bocuse generously gifted the bottles to Frédéric Panaïotis, Ruinart’s chef de cave—all but four, that is, three to be kept in Lyon and one to be tried by a privileged coterie of assembled journalists and sommeliers chez Bocuse.

Frédéric is delighted with this generous bequest, and the 14 bottles are now the most senior to be stored at La Maison Ruinart in Reims, the previous oldest discovered in Alsace and dating from 1929. The 14 bottles will take pride of place in a new oenothèque cellar that Ruinart is planning to open over the next 12 months or so. The rigors of World War II and the depredations of Occupation (cases were raided at whim by Reims’s thirsty Wein Führer) meant that in 1945 Ruinart had stocks of fewer than 10,000 bottles, none of any age. A discovery such as this is all the more special, therefore.

Panaïotis has also unearthed the cellar books of the Ruinart chef de cave at the time, Maurice Hazart, who had held the position since 1911. 1926 was embedded in an era when tradition in Champagne was continually challenged, the prewar riots not too far behind them, and the codifications that formalized things such as the échelle des crus and the regional delimitations still to come. And then, of course, another world war, which threw everything into disarray once again. On the broader stage, 1926 saw the French bombardment of Damascus after the Dreuze riots, the general strike in England, and the exploits of Al Capone in Chicago. The birth of Paul Bocuse had a creative counterbalance with the deaths of Rudolph Valentino, Greta Garbo, and Claude Monet. Great artists, one and all.

Relief redoubled

Although the vintage itself may not be of the caliber of 1928 and, especially, 1921, 1926 was deemed to be a good year, with plenty of sunshine and rainfall at opportune moments. Hazart wrote at the time, “The wines from 1926 are elegant but not very full-bodied. They are good without being exceptional. They are not a 1911 or 1921, but they are at least as good as 1923.” Such modesty! The vines, ravaged by both phylloxera and world war, were probably young and relatively unproductive. One is invited to speculate on the blend, which was probably not too far from today’s wine, but without Meunier. Technical analysis of a sample taken from an open bottle has revealed that the ABV is 13% and the residual sugar is 17g/l—both a touch higher than Frédéric estimated on tasting—but, more interesting, that the pH is (even) lower than anticipated, at 2.83. (One would expect these days somewhere around 3.05–3.10.) The inference Frédéric draws from this is that there was no malolactic, which does not surprise him for this period. The high acidity helps explain both why the RS was higher than he estimated and why the wine is so harmonious in its balance. The bottle is labeled as extra-dry, implying a certain degree of sugar, itself in keeping with contemporary custom.

When Maxime pulls the cork—delicately, oh so delicately—there is general relief that it comes out whole, even if without much by way of gaseous panache. This relief is redoubled on tasting. There is gentle vestigial effervescence and enough freshness behind the amber robe and gamey aromatic to justify all the anticipation and ensuing ceremony. As the only Englishman present, I am quietly pleased to note that the wine is labeled as Carte Anglaise, one of three cuvées made by M Hazart in 1929 and, if one may hazard a guess, presumably intended for the Anglo-Saxon market. A further anomaly is the spelling of Reims with an “h” on the label, as in “Rheims,” further proof of this Champagne’s venerability and authenticity. Frédéric compares the style to that of a Tokaji—an interesting observation, more than supported by the marmalade aromatic and high-acid, gamey taste and texture, if not, of course, by the residual sugar. Everyone is happy, even more so with the further treat of lunch in Bocuse’s dining room, with famous dishes such as Valérie Giscard d’Estaing’s soupe aux truffes noirs Elysée and volaille de Bresse en vessie on the menu. Four more Ruinart wines accompany the food, together with a 2019 Meursault from Domaine Faiveley and a 2020 Côte-Rôtie from Domaine Burgaud. A very special day, one cannot deny.

Tasting Ruinart

Restaurant Paul Bocuse, Lyon, February 23, 2023

R de Ruinart 2016 (48% C, 32% PN, 20% PM; dosage 5g/l; disgorged July 7, 2022)

This wine has not yet been released. It is worth remembering that the R de Ruinart Millésimé is reserved for the French market, which still makes up 50 percent of Ruinart’s sales, higher than the other deluxe houses within LVMH.

The midsummer heatwave (temperatures above 104°F [40°C] at one point in July, then drought) has informed but not dictated the style of this wine. Gastronomic, for sure, with an almost tannic mid-palate this is powerful yet subtly so, with a smoky, gently yeasty backdrop to the core of agrumes and yellow fruit. | 94

R de Ruinart 2015 (44% C, 44% PN, 12% PM; dosage 6g/l)

A challenging year, pace Fred, marked by both extreme dryness early to mid-season and then extensive rainfall toward the end of August. A distinctive spicy note takes us beyond the initial allure of guava and nectarine; cardamom, fennel, and even aniseed are all noted, complexity suitably underscored. Broader-shouldered than the 2016, Pinot Noir to the fore. | 92

R de Ruinart 2010 (magnum) (55% C, 45% PN; dosage 5.5g/l)

Toasty, ripe, and generous, child of what Fred describes as “noble reduction” (the contrast between toasty notes engendered thus, and a more overt “oaky” texture is writ large when we try it next to the Faiveley’s 2017 Meursault). 2010 was a strong year for Chardonnay, and the fruit is suitably pure and expansive, pear and ripe apple standing out, with hints of apricot behind and, further back still, hazelnut and tobacco leaf. | 93

R de Ruinart 2009 (magnum) (51% PN, 49% C; dosage 5.5g/l)

Fred does not like the widely used descriptor solaire for 2009; the year was dry more than anything else, he reminds us. Be that as it may, the wine is weighty, rich, and ripe. Praline, dried fruit, and hazelnut underwrite the impressive finish after imposing but not overbearing mid-palate weight. | 93

R de Ruinart 1995 (magnum) (48% C, 52% PN; disgorged 1999; dosage 5.5g/l)

Fred compares the warm summer to those of 1976 and 1983 (none as “extreme” as 2003 or 2018), and we are served from an old-style magnum; the now-ubiquitous bulbous-shaped bottle was only (re)introduced after 2004. A deep Spanish gold signals a change of register; this is confirmed by a nose of tarte tatin, quince, and—Fred looks at me (the only Englishman in the room) and says—“shortbread.” Yes, shortbread—spot on! Hints of mushroom and white tobacco, too, and a seductively soft finish. Absolutely singing now and a must for those of us who like a savory style of mature Champagne. | 95

Dom Ruinart Blanc de Blancs 2007 (magnum) (100% C; dosage 4.5g/l)

Served with a suitably whimsical selection of amuse-bouches (oysters and Roquefort are not without their challenges), the 2007 is itself spicy, resourceful, and long. Gingerbread and aniseed flourishes beyond rapier-like acidity and a confident orchard-fruit core. | 93

Dom Ruinart Blanc de Blancs 2010 (100% C; dosage 4.5g/l)

The current release, the 27th since 1959, aged on cork. Such a delicate filigree, but then symphonic power; Burgundian resonance and purity of texture. Unfazed by the lobster and zander quenelles, yet another Bocuse signature dish. The new tirage regime (cork rather than crown cap) is the most important of Fred’s tenure thus far; he joined in 2007. He compares the wine to a Corton-Charlemagne. | 94

Dom Ruinart Blanc de Blancs 1993 (magnum) (100% C)

A magnificent magnum of Chardonnay, the year in question cool and classic, so maybe a little like 2013 or 1988. An instructive comparison with the more savory and evolved 1995 R de Ruinart tasted a little earlier. More purity and restraint here, dried fruit and a chalky, softly spicy backdrop, but no lack of mid-palate generosity. | 96

Ruinart 1926 Carte Anglaise

Vinifed in wood and aged on the lees under cork (the best practices are cyclical, it seems), and probably disgorged relatively soon afterward. The 36-month aging rule had yet to be introduced, and many wines would have followed market demand, so this may well have been disgorged a mere two years after being laid down. 1929 was to be Ruinart’s bicentenary.

The cork is impressively robust (if somewhat silent on release), ditto the wine, from its soft amber/brown color, to the nose of dried apricot, brown-sugar marmalade, and nutmeg. The acidity certainly preserves the spirit… then mushroom, dried fruit, oranges and plum. Finally, a whisper of Cognac and tobacco. A vin de contemplation, just shy of centurion status but far from reticent in other respects. Well worth the detour! | 95