Yquem 1847. Behind this fabled name and date lies one of the most iconic events of the 19th century: how a Russian grand duke paid the highest price ever recorded at the time for one tonneau (that is, 900 litres or 1,200 bottles or 100 cases) of Yquem from one of the greatest vintages of the century.

The bare bones of the story are that Grand Duke Constantine, the brother of Tsar Alexander II, visited Bordeaux in 1859 and bought one tonneau of this wine, which was bottled into gold-engraved crystal decanters. The price was 20,000 francs. To put this price into context, Yquem had sold two thirds of the superb 1858 vintage en primeur for 3,500 francs per tonneau and later sold it for 10,000 francs per tonneau. And when Baron James de Rothschild bought Lafite in 1868, six casks of the exceptional 1865 were sold for 3,000 francs each (that is, 12,000 francs per tonneau).

When the great growths of Bordeaux were classified in 1855, the Médocs were headed by four premiers crus, but among the ‘Vins Blancs Classés de la Gironde’, Yquem was placed first under the heading of ‘Premier Cru Supérieur’, followed by nine crus designated ‘Premiers Crus’, making its position unique.

The special position of Yquem was nothing new. When Thomas Jefferson, then ambassador of the fledgling United States of America, visited Bordeaux in the 1780s, he was greatly impressed by Yquem, buying 250 bottles of the 1784 vintage for himself and subsequently of the 1787 vintage for George Washington. Of all the wines in Bordeaux, he wrote, these most perfectly suited the American taste. The US Consul in Bordeaux, looking after Jefferson’s interests, commented on the ‘exorbitant’ prices Jefferson was obliged to pay.

One interesting point that emerges from Yquem’s archives is that, prior to 1861, the crop was not ‘assembled’ as it is today. Instead, the wines made from each trie were sold separately under names such as tête, centre, queue or ensemble – the latter, presumably, for a wine assembled from several lots. The 1847 was seemingly still in cask 11-12 years after the vintage at the time of the grand duke’s visit.

In the 19th century, comparative tastings such as we have today were unknown, so all we know is that certain vintages had an exceptional reputation. Today, we know that 1921 was the benchmark for Yquem in the 20th century and continues to be so in the 21st; and we can taste and compare, as I did, most memorably, at Yquem when Comte Alexandre de Lur Saluces hosted a tasting in June 2003, before his retirement at the end of the year. The vintages selected for this tasting were ’97, ’95, ’90, ’83, ’76, ’67 – covering the period of Comte Alexandre’s stewardship – then ’62, ’55, ’49, ’37, ’29 and ’21. In addition, the ’98, ’96 and ’45 were drunk at lunch. Even in this context, the ’21 was still supreme, less maderised and more unctuous than the ’37, more complex than the wonderful ’29. It was most nearly approached by the marvellous ’45 at lunch. It is clear that in the 19th century, the 1847 held the same sort of position as the 1921 did in the 20th.

On 7 June 1867, a dinner was held at the legendary Café Anglais. The Dinner of the Three Emperors was attended by Tsar Alexander II, his son the future Alexander III and King Wilhelm of Prussia, who, in 1871, was acclaimed German emperor by the German princes in the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles. The 1847 Yquem was served with a fish course, before the monarchs moved on to Château Margaux 1846, Château Latour 1847 and Château Lafite 1848! After the Russian purchase, this was probably the most celebrated moment in the story of this remarkable wine.

The Russian love affair with Yquem in particular and sweet wines in general did not end there, however. Bottles of Yquem 1865 turned up in the famous Massandra cellars of the last tsar, Nicholas II, and some were offered at auctions of the wines from the Imperial vineyards in the Crimea by Sotheby’s in 1991, 2001 and 2004. In 2001, five bottles were sold for the staggering price of £6,200 each. The wine had been regularly recorked and was in superb condition. The analysis showed 10.5% alcohol, and 153g residual sugar, so still extremely sweet even by modern standards.

In the Massandra vineyards, attempts were made under the guidance of Prince Golitzin to produce Yquem-style wines. The oldest surviving example was called Ai-Tador Yquem, made c.1880. But as late as 1929, a wine was made called Massandra Yquem No. 65, with 13.4% alcohol and 257g residual sugar – so the men who succeeded the tsars had very similar tastes. Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev actually visited Yquem in the last days of Marquis Bertrand de Lur Saluces’s life in the 1960s. Some of the locals were so outraged that they littered the road with tin-tacks to sabotage the May Music Festival that was held there shortly afterwards. There were numerous punctured tyres, and there was total chaos in the narrow roads leading to the château!

Something should also be said of the history of this great property. The château itself stands majestically on the Sauternes skyline, a complex mixture of feudal fortress with elegant Renaissance additions. In the Middle Ages it had been a royal estate, belonging first to the English crown then, after 1453, to the French crown, before being acquired in 1593 by the Sauvage d’Eyqem family. In 1785, the Sauvage heiress Françoise-Joséphine married Comte Louis Amedée de Lur Saluces, godson of Louis XV. The Lur Saluces had been owners of Yquem for only two years when Thomas Jefferson visited. By the time of Grand Duke Constantine’s visit in 1859, the estate was in the hands of Romain Bertrand de Lur Saluces, grandson of Louis Amedée.

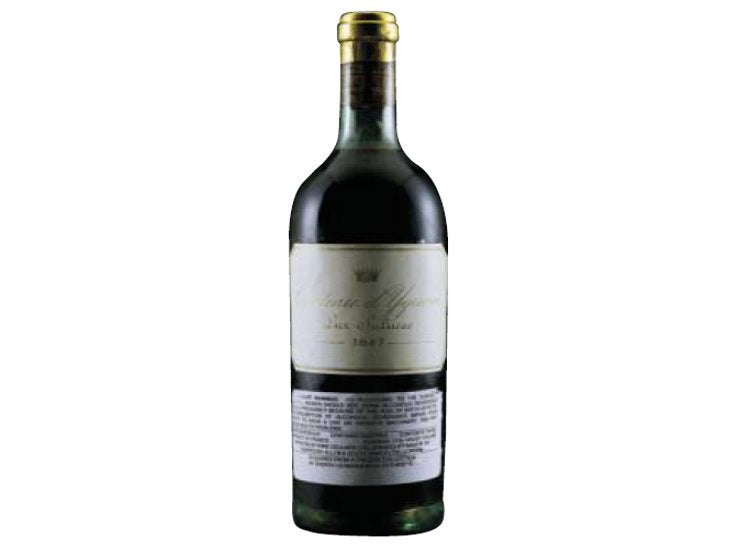

The château label is of endearing and enduring simplicity, in essence unchanged since the 19th century. It simply states Château d’Yquem, Lur Saluces and the vintage – none more famous than 1847.