In 2022, Ca’del Bosco celebrated the 50th anniversary of its inaugural vintage. Tom Stevenson took the opportunity to catch up with its founder Maurizio Zanella in Franciacorta, taste the range, and look deeply into his technological innovations.

We met up at Da Vittorio, a family-owned Relais & Châteaux hotel with a three-Michelin-star restaurant near Bergamo. It’s a personal favorite of Maurizio’s so, when he made an appearance, everyone—from the staff, to the customers—recognized him and wanted to shake his hand. As always, Maurizio was dressed casually but impeccably: a walking advert for Gucci chic. Maurizio loves Gucci; he even provides his hospitality staff with Gucci scarfs.

He apologized for being late, but I told him he wasn’t, since it was only 8.30pm and he was, therefore, on time. To which he seemed puzzled, claiming his secretary had texted that him dinner was for 8pm. Then the penny dropped for both of us, as we realized his secretary knew Maurizio better than he did himself. I raised my glass and declared, “In that case, I’m 15 minutes late!”

It was one of those balmy nights when you could sit on the terrace until midnight in short sleeves and feel totally relaxed—unlike the next evening, when I was on my own and it was raining. No matter how hard Maurizio tried to restrain the number of courses when dining, they just kept coming. They were supposed to be tasting-menu size, and in a Yorkshire Michelin-starred restaurant, I suppose they would be. In any case, it was all sublime and I was not complaining. When I dined alone the next day, however, and they offered me ten courses, I asked as diplomatically as I could for an absolute maximum of five. The waiter smiled and said “So, only eight courses then?” to which I replied, “Only five maximum please.” The waiter’s smile widened, “Okay, five… and a surprise!” and he served me ten! All different from the night before, but all as sublime, of course. The sommelier gave me a small glass of Yquem 1928 from another table, which had left one third of the bottle for the staff to experience. Fabrizio thought I might appreciate the gesture, and I most certainly did. There are whole generations who would like to be a celebrity, but not me. I don’t want to be recognized by anyone … except the sommelier, maybe.

From Bosc to Bosco

Maurizio was born in 1956 in the provincial capital of Bolzano, Alto Adige, to Albano and Annamaria Clementi Zanella. When you drive up to Ca’del Bosco, you might notice the road is called Via Albano Zanella and, of course, Cuvée Annamaria Clementi is Ca’del Bosco’s deluxe cuvée.

It was love at first sight for Albano and Annamaria, who were married within three months of meeting, and they soon had a bouncing boy to contend with. Maurizio was just two years old when his parents moved from Bolzano to Milan in search of fortune. Initially, they were so cash-strapped that Albano had to ask the manager of the building in which they had a flat if he could have the deposit back so he could bring Annamaria home. She had just given birth to Maurizio’s sister Emanuela, and Albano had to pay the clinic’s bill.

In Milan, the family finances began to improve when Albano, an engineer, set up his own transport company with friends. As he began to earn dividends, so he was determined to invest in property. In 1964, Albano noticed an advertisement in Corriere della Sera, a local daily newspaper, for the sale of a 5-acre (2ha) plot in Erbusco and decided to take his family to look over the place. They found a very rudimentary shack surrounded by oak and chestnut trees. They entered to encounter an old lady, whom Annamaria asked for some water to quench Emanuela’s thirst. The old lady nodded, lifted a trapdoor, and revealed a number of tubs that collected rainwater. From one of these she filled an empty wine bottle. Later, Annamaria Clementi would describe the contents of those tubs as “full of everything from frogs to lizards and insects”. The old lady then filtered the water through linen cloths into a pot, which she boiled over an open fire. After cooling, it was offered to Emanuela.

Because the place was without water, electricity, or sewage, Albano was horrified, but Annamaria had fallen in love with it. Unlike her husband, she was born in the very north of Lombardy, in Bormio, in the Valtellina valley, a stone’s throw from the Swiss border, with a vista of snow-capped mountains. She told Albano that all the places they had viewed in the Bergamo area looked “flat and plain” and she felt she was “dying”, whereas Ca’del Bosc sat on a hillside and made her feel more at home.

Albano was left with no option but to purchase the property, and the first thing he did was to dig a well, even though that cost him more than the land itself. The Zanella family remained in Milan, visiting Ca’del Bosc every weekend at Annamaria’s insistence. Albano hired Antonio Gandossi to manage Ca’del Bosc and build a proper, albeit somewhat rustic, farmhouse. He trusted Gandossi with a cheque book and instructed him to buy up any surrounding properties he could find, which he did quite successfully and often at very little cost. In those days, the area was well and truly in the back of beyond, with any available property uncultivated, either abandoned or woodland. Albano imagined it would become a smallholding with cattle, sheep, horses, and an orchard, and, as part of this strategy, a vineyard was planted in 1968 (under the guidance of Franco Ziliani of Guido Berlucchi), when Maurizio was just 12 years old.

There was no ambition beyond supplying Berlucchi with grapes and retaining some of the production for home consumption, as was the habit of so many in Italy at that time. It was also very early days for Italian fine wine. The Franciacorta DOC had been granted only the year before (1967) and Italy’s entire appellation system was itself so young that Franciacorta was just the fifth DOC to be announced. As was the norm in those early years, the Franciacorta DOC was for still wines as well as sparkling, and those still wines could be red or white, dry or sweet, or passito in style.

Today’s reputation of Franciacorta as a great sparkling-wine terroir was thus a long way off. There were only 11 wineries making sparkling wine locally, and Guido Berlucchi represented 80 percent of all sparkling Franciacorta production. Franco Ziliani had been the first to produce sparkling Franciacorta as recently as 1961, making him the most experienced producer locally. This was why Albano asked him to plant a small vineyard and to teach Antonio Gandossi how to train and prune vines. So, it was by accident that Albano laid down the first piece of the jigsaw that would eventually become the famous Ca’del Bosco of today.

Boy on a bike

After a few years of misbehavior at a couple of schools, Maurizio was sent by his parents to work on the docks of Manchester in the UK as a punishment. On return to Italy, he was exiled to Ca’del Bosc, where he was made to study accounting at the local college in Iseo. During the week, he grew to love Ca’del Bosc by riding his motorbike over its hills and through the woods, but he remained rebellious and had no idea what to do with his life. At the weekends, when his parents came to visit, he avoided confrontation by making the reverse trip to see his girlfriend in Milan.

In 1972, Maurizio went on a wine study trip to Burgundy, Champagne, and Paris, with a bus-load of Lombardian wine producers. He had told his mother he wanted to make wine, but in truth he simply fancied the opportunity to enjoy an unsupervised weekend in Paris at the age of 16. That might have been his intention, but his visit to Champagne was an eye-opener. He got it—not simply the quality of Champagne, the greatest sparkling wine in the world, but the branding of Champagne and how its deluxe cuvées could cross the boundaries of wine to become icons of haute couture and art. That and its proximity to Paris, which was also the capital of haute couture and art. For someone living in Milan, one of the four fashion capitals of the world, it struck a resonating chord, even if he could not have cared less about fashion when he was in the city. Until then, all he cared about was his motorbike.

Maurizio might have gone on that trip based on a lie, but when he returned, he really did want to make wine. So much so, in fact, that he went directly to see his father. Until then he always sought the help of his mother to persuade his father. This time, however, he was so fired up with his newfound passion that he went directly to his father and found him surprisingly receptive. As Annamaria would later confirm, “For the very first time, Maurizio’s father saw a passion in his eyes. That was why he encouraged him.”

Rebel with a cause

Excitedly, he told his father of his plan to expand the vineyards, build a cellar, and make a sparkling wine that would become an iconic brand like the most famous Champagnes. The rebel had found a cause. Albano immediately responded, “If that is your idea, then you should do it!” and when Maurizio asked how a 16-year-old could fund his dream, his father told him to use his accounting qualifications to draw up a business plan and go with his mother to ask the bank manager for a loan. This he did, and managed to secure a 160 million Lira mortgage (equivalent of $160,000 then, $1.8m today), little realizing that behind the scenes his father had already secured the loan. From that point on, despite underwriting the venture, Albano never interfered. He always let his son run Ca’del Bosco as he wanted and never let him feel as if he was not the entire driving force of the venture, which in every important way he was. (Maurizio had added the “o” to Bosc to transform it from what he perceived as the hard local dialect into a more elegant, classical Italian Bosco.)

Maurizio ran Ca’del Bosco as he saw fit, however, I get the feeling that he never felt out of his father’s shadow in life generally. Even as a grown man successfully running Ca’del Bosco, he still turned to his mother, such as when he wrote off a brand new Range Rover and conspired with his mother to buy an identical one so that his father would not notice!

Yet the only time that Albano attempted to interfere in Ca’del Bosco was when it had grown to 150 acres (60ha) and was steadily selling 500,000 bottles a year. Maurizio’s father pointed out that he could remain totally independent if he were willing to stay with these numbers and to forget about all the wild and wonderful R&D projects he was always dreaming up. If he wanted to pursue his dreams, however, he would have to find a partner to share the financial burden—or else he could go bust.

No one who has created anything worthwhile wants someone else to steer the ship, so it was little wonder that Maurizio fought for two years against the idea of selling out. Part of Albano’s brilliance, however, was to recognize that such a decision had to be Maurizio’s and Maurizio’s alone, and he knew that would take time. He therefore brought up this matter long before such a decision would have to be made and patiently waited until Maurizio finally realized that a partnership was in his own best interest.

In 1994, an agreement was made in great secrecy between the Zanella and Marzotto families. The Marzotto family owned Santa Margherita; a large group now, but even back then it had built up a portfolio that included, among others, Kettmeir in Alto Adige (winners of Best Italian Sparkling Wine at The Champagne & Sparkling Wine World Championships in 2022; see p.31). The meeting took place at the Alpine lodge built by Albano for his wife’s retirement in Ossana. Set in the upper Val di Sole of Trentino and surrounded by the mountains and forests Annamaria loved, the Marzotto family could come and go without drawing attention. By all accounts, Albano was in charge of negotiations for the Zanella family, and he drove a very hard bargain. For an undisclosed sum, the Santa Margherita group took a controlling 60 percent shareholding in Ca’del Bosco, but the Zanella family retained ownership of the winery itself, its cellars and grounds, and the 150 acres of vineyards that existed at the time of the contract. The winery and vineyards are leased to Ca’del Bosco, which has to pay rent to the Zanella family, and all future investments in vineyards, technology, and research would be split 60/40.

From a fortuitous cause, to a farsighted pioneer

It was this 60/40 split that enabled Ca’del Bosco not only to expand to 620 acres (250ha) of vineyards with a production of almost 2 million bottles, but also to invest in what is uniquely the most cutting-edge, high-tech sparkling-wine winery in the world. Uniquely because it comprises some extraordinary Ca’ del Bosco patented technology. Having to pay only 40 percent for every investment in growth must have been such a relief, but having to pay just 40 percent of all the research, innovative technology, and, let’s face it, more artwork than you can chuck a Rhino at, must have felt like a miracle for a visionary like Maurizio, who wakes up every morning with a brand new, potentially very expensive, and often very whacky, idea.

How does he feel about losing control of Ca’del Bosco? If truth be told, the Marzotto family has been as benign as any financial partner could possibly be. There are always discussions to be had between major shareholders in any business, but for all intents and purposes, the Marzotto family has left Maurizio to run Ca’del Bosco as he sees fit. Why mess about with a winning formula? Why expend energy and time trying to micromanage something so iconic than they have bought into it?

As for Maurizio, he still does what he does. Life is no different for him, although, without 100 percent of the financial burden, it is perhaps a little easier. He is much richer today, owning just 40 percent of Ca’del Bosco, than he would have been had he resisted a partnership back in 1994. In some years, the Ca’del Bosco partnership spends more in investments than it turns over in sales. If he had tried that on his own, he would have gone bust. No, Maurizio has the best of both worlds, and that has enabled him to drive his iconic brand to greater heights.

What makes Ca’del Bosco different?

All of Ca’del Bosco’s vineyards are now certified organic. The vineyards of any wine estate represent 100 percent of the wine’s potential, just as its grapes, when picked, represent 100 percent of the wine’s potential quality. The terroir determines its potential, but that includes the varieties of vine chosen, how they are planted, how old they are, how they are trained, pruned, cared for, and harvested, but no winemaker ever gets close to achieving 100 percent of a vineyard’s potential. While the grapes when harvested will always fall short of the vineyard’s potential, however hard its owner might try, each grape at the time of picking has its own intrinsic potential. As Johnny Hugel used to say, the moment a grape is picked, its potential is 100 percent and dropping as the clock begins ticking. The winemaker can never improve on that 100 percent, he or she can only hope to preserve as much of it as possible, and each step taken from here will play a hugely significant part in this respect.

Not everything Ca’del Bosco does is unique, but a lot of what I call its basic qualitative steps are rarely found in other wineries. Certainly not the complete list. In addition to this, there are procedures that are proprietary, and it is these that make Ca’del Bosco truly unique.

All grapes are picked by hand and transported in stackable 35lb (16kg) crates.

Each crate is bar-coded in the vineyard and this coding is used to trace the origin of every grape through the winemaking process.

The grapes go straight to cold rooms, to stop any oxidation.

When the grapes have cooled, the automated pallets travel to Ca’del Bosco’s “Berry Spa” where robotic arms gently empty them onto a conveyer belt.

The “Berry Spa” consists of four separate lanes, enabling Ca’del Bosco to wash and dry four different grape varieties or four different locations of the same variety.

Initially, there is a manual sorting to remove the easily observable foreign material, such as leaves, bad fruit, and creepy-crawlies, but much can still get through at this stage, hidden under or inside bunches.

The bunches continue by conveyor belt to three water baths and one drier.

• Bath #1 is pure clean water at 54ºF (12ºC) through which bubbles are generated to clean by gentle agitation. As the grapes exit the bath, they are softly sprayed with pure clean water to rinse away the bath water.

• Bath #2 is pure clean water at 54ºF to which citric acid has been added for its antioxidant, antiseptic, and antifungal properties. As the grapes exit the bath, they are softly sprayed with pure clean water to rinse away the bath water.

• Bath #3 is again pure clean water at 54ºF to provide a thorough rinse and once more as the grapes exit the bath, they are softly sprayed to rinse away the bath water.

• The bunches move onto a pair of cold-air blow-driers designed by the salad industry to dry tender plants without bruising.

• The chilled, washed, and dried grapes for sparkling wine go straight by conveyor belt to one of the 11 Wilmes pneumatic nitrogen-flushed presses (still wine grapes arrive here via a destemmer).

From pressing to bottling, the entire Ca’del Bosco winery is gravity-fed, even to the point that when wines have to be moved from one tank to another, such as in blending a final cuvée, there are two giant lifts into which the vats can moved and, to avoid disturbing the wine, the vats are lifted upwards at a snail’s pace.

The final point of difference in the sparkling wine-production process comes at the point of disgorgement and corking, which takes place in a nitrogen-filled chamber on the bottling line:

• As it is essential to have entry and an exit flaps, the nitrogen-filled chamber maintains a positive over-pressure, to prevent O2 leaking in.

• At the point of disgorgement, the TPO is non-existent.

• The headspace is drip-fed with nitrogen prior to corking, almost entirely eliminating the oxidative shock of disgorgement (not complete elimination as the cork itself will release between 2.5mg and 3mg of O2 per bottle, but this is closer to micro-oxygenation than oxidative shock).

There are other factors, but essentially it is the combination of washing the grape and disgorging-dosage-corking under nitrogen that enables Ca’del Bosco to add no SO2 to most of its wines, although a very small amount is added to the longest-aging cuvées such as Cuvée Annamaria Clementi

The “Berry Spa”

When I first saw this in 2014, I was blown away, and there were only two lanes then, whereas there are an even more impressive four lanes now. While I had seen the odd few organic and biodynamic producers plunge bunches into a barrel of increasingly murky looking water prior to fermentation, only Maurizio Zanella, the founder of Ca’del Bosco, could dream up, let alone devise, a fully automated system to wash and dry an entire crop of a substantially sized wine estate. It was a wake-up call. It made me think, “Why aren’t all grapes washed before the winemaking process?”

We wash any freshly grown ingredient before eating or cooking, so why don’t winemakers wash grapes before fermenting? Some might say that it is unnecessary because anti-bacterial agents such as SO2 will cleanse the must… but cooking sterilizes ingredients, yet does not stop us from washing fresh ingredients. It is a precaution. As for wine, there are a lot of bugs, creepy-crawlies, leaves, and other extraneous matter that even the most fastidious manual sorting will not remove—especially the tiniest life forms roaming around inside bunches. Then there is the chemical and inorganic residue from spraying grapes. While there might be more of this found on conventionally grown grapes, even certified organic producers are allowed to spray their crops with copper sulfate.

Since 2008 and, particularly, 2014, Ca’del Bosco’s wines have had a greater purity. It is not simply a matter of less SO2, thanks to washing the grapes and disgorging under nitrogen. It is also the absence of certain organic and inorganic material that is foreign to both the fruit and its terroir, thanks to the washing alone. How that absence imprints itself on the fermentation process gives the wine more precision and is, by definition, more authentic and expressive of place and grape.

When both Maurizio and I are long gone, every winery will wash its grapes and consumers everywhere will take it for granted, like washing hands before the preparation of food. Why wouldn’t they?

Disgorging and corking under nitrogen

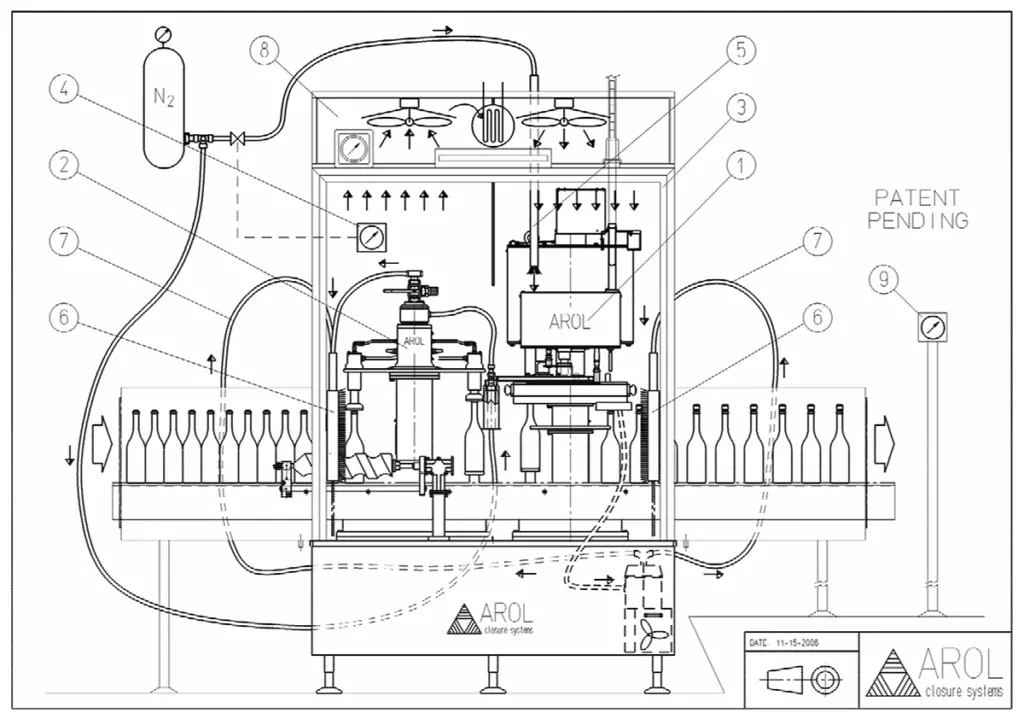

Nitrogen chamber corking system is composed of a corker [1], preceded by a carrousel [2] aimed at injecting N2 in the neck space of each bottle, to replace the existing air, collect it, and bleed it outside. Both turrets are fitted in a sealed chamber [3], to keep the concentration of O2 at a steady value; such concentration is controlled by the detector [4] and adjusted by feeding N2 through the ducts [5] and [7]. To reduce the flow of the gas mixture between inside and outside as much as possible, gas curtains [6] are placed at the entry and exit of the chamber and use the flow exiting the injection carrousel. [8] and [9]: Nitrogen detectors.

Patented by Ca’del Bosco in 2005, disgorging, dosaging, and corking inside nitrogen is probably the Betamax to Jetting’s VHS. This was the year that Moët began trialing the beer industry’s continuous stream form of Jetting (see “Jet-Age Fizz,” WFW 48, 2015, p.62), following the ground-breaking paper that was published by the CIVC in 2003 quantifying oxygen ingress between disgorgement and corking. The beer industry’s jetting lacked the precision required for Champagne and it was not to be until 2009 that LBM Industries in Reims patented a nitrogen-based pulse-Jetting technology. In theory, Ca’del Bosco had a four-year window in which to market this device, but Jetting itself was not an easy sell and, although cheaper, it took longer than four years to build up its own sales. Had it been invented ten years earlier, licensing could have paid for its development, but the only benefit for Ca’del Bosco now is that it has exclusive use of what might be a superior technology. Anyone who has read my position on Jetting will know that I am a big fan, and yet, looking at both Jetting and Ca’del Bosco’s nitrogen chamber, I get the feeling that the latter has the edge. A feeling, however, is not science, and I would dearly love to see these two systems tested under laboratory conditions.

Franciacorta’s single greatest promoter

Ca’del Bosco is a globally recognized luxury sparkling-wine brand. Maurizio might not be the Father of Franciacorta, but he has become its single greatest promoter and he embodies the notion that world-class sparkling wines can be produced here.

This praise does not come unqualified. Ca’del Bosco has a major flaw. Maurizio once claimed in an interview, “I am Taliban when it comes to quality. There is no compromise.” And yet he continues to use clear-glass bottles for Cuvée Prestige and Cuvée Prestige Rosé, which is a compromise too far.

When I put this to him, he pointed out the orange cellophane wrapping, used to protect the wine from light-strike. So, I explained to Maurizio that I have seen bottles of Roederer Cristal with their protective covering removed in a brightly lit fridge in a supposedly top-flight establishment. I wish Roederer did not use clear-glass bottles, but I recognize the 150 years of history wrapped up in the Cristal bottle, and if Roederer is willing to risk the quality and reputation of one of the monumentally greatest Champagnes in existence, then so be it. For everybody else, however, the only excuse is marketing and how pretty the bottle looks.

As I put to Maurizio “If the protective wrapping is removed and bottles are put on display under bright lights even where there is team of professional sommeliers reporting to a head sommelier, who in turn reports to a wine director, what do you think happens behind closed doors of ordinary folk at home?”

Clear glass is the most glaring flaw at Ca’del Bosco, and its solution is profit-plus, as dark amber glass is cheaper and there would be no need for protective wrapping. Traditional corks are another flaw on the quality control checklist and it is one that applies to thousands of other sparkling wine producers as well. The threat they represent is less obvious and less known. Virtually all of the corks that I have drawn from a bottle of Ca’del Bosco have been beautiful to look at and sweet to smell, but even the best natural cork discs on the most expensive traditional stoppers are useless. They are cut the wrong way, leaving the lenticels to act like oxygen super-highways (see my “Cutting Remarks,” WFW 70, 2020 p.94). I am one of DIAM MytiK Diamant’s biggest fans, but I understand why that is not the solution for those producers who want the aromatics associated with natural cork. I would urge them, however, not to risk their wines aging on the rough and raw aromatics of the agglomerate just for the sake of picking up some natural-cork aromas along the way. Instead, ask your cork supplier to quote you for traditional sparkling wine stoppers with the discs cut the right way. Yes, they will be expensive, so this will not be a profit-plus answer, but if a producer believes in the quality of his sparkling wine, it will be a cost-effective solution.

Tasting Ca’del Bosco

All wines were tasted at Ca’del Bosco on August 30, 2022, with the exception of any older vintages and blends mentioned in the notes. The sparkling wines are, of course, DOCG Franciacorta, whereas the still whites are DOC Curtefranca and the reds are IGT Sebino. In 1995, when the sparkling wines of Franciacorta were elevated to DOCG status, the delimited region was restricted to just 19 of the original 23 communes, and any still wines had to be sold as DOC Terre di Franciacorta, which in 2008 changed to DOC Curtefranca.

Curtefranca is a modified transposition of Franzacurta, which itself is the origin of Franciacorta. Franzacurta was first mentioned in 1277, when an injunction in the Eighth Book of Statutes of Brescia defined an area to the south of Lake Iseo, between the Rivers Oglio and Mella as a tax-free haven for goods transported to Brescia.

Curtefranca may be produced as either red or white, but Ca’del Bosco uses the DOC for its white wines plus the Corte del Lupo Rosso, preferring to make and market its other reds under the IGT Sebino for the greater flexibility this entry-level appellation offers.

SPARKLING WINES

Cuvée Prestige Edizione 44 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl) (81.5% Chardonnay, 1.5% Pinot Bianco, 17% Pinot Nero; 12.8% ABV; 0.9g/l RS)

This 2019-based blend is composed of 197 plots with reserve wines from 2018 (26%) and 2017 (3%). Cuvée Prestige and Cuvée Prestige Rosé are the most disappointing and inconsistent wines in the entire range. How could this be for a producer that rarely disappoints and prides itself on consistency? Is it a coincidence that they are the only wines bottled in clear glass? I doubt it. The two absolute standouts for me have been Edizione 30 (below) and Edizione 41 (gold medal at CSWWC 2019), but here’s the kicker—they were both 75cl bottles and the magnum of Edizione 41 was extremely disappointing. A bit like the magnum of Edizione 44. So, what happened to the “magnum effect”? The magnum effect worked for Edizione 42 both here and in 2020, when it was on the market, as it did for 43 in 2021, but it was more silver than gold. I believe the potential quality of Cuvée Prestige is nothing less than outstanding, but it is being ruined by its clear glass bottles. And seeing the magnum effect reversed for Edizione 44 when tasted at the winery itself leads me to suspect that at least some of these clear-glass bottles and magnums are accumulating up to 60 minutes light exposure prior to being wrapped in their protective orange-colored cellophane. Wherever the light gets in, be that at the winery, in a restaurant, a shop, or the customer’s home, it’s a shame. I cannot remember ever detecting a fully developed light-strike stink on any Cuvée Prestige, just disappointment, and this 75cl might seem very pure and fruity, but it leaves me wondering what might be missing. I wish Maurizio would get rid of these damn clear-glass bottles. | 87

Cuvée Prestige Edizione 44 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (81.5% Chardonnay, 1.5% Pinot Bianco, 17% Pinot Nero; 12.8% ABV; 1.4g/l RS)

Same composition as the 75cl bottle, which, strangely, I much preferred! | 75

Cuvée Prestige Edizione 42 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl) (83% Chardonnay, 5% Pinot Bianco, 12% Pinot Nero; 12.5% ABV; 1.5g/l RS)

This 2017-based blend is composed of 139 plots with reserve wines from 2016 (22%), 2015 (6%), and 2014 (3%). Fruity, okay, with no obvious defects, but not special and totally different to the magnum below. | 83

Cuvée Prestige Edizione 42 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum)

(83% Chardonnay, 5% Pinot Bianco, 12% Pinot Nero; 12.5% ABV; 1.5g/l RS)

Same composition as the 75cl bottle, but this is classic Franciacorta. Some charred notes on the nose; clean, fresh citrus and white-fruit palate. Initially quite smart, but the finesse drops away on the finish, hence one point away from 90. | 89

Cuvée Prestige Edizione 36 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl)

(75% Chardonnay, 10% Pinot Bianco, 15% Pinot Nero; 12.5% ABV; 0.5g/l RS)

This 2011-based blend is composed of 149 plots with reserve wines from 2010 (26%) and 2009 (14%). A commercially disgorged preview sample, this is as fresh as a daisy, with fine, classic structure, supported by a lovely, soft mousse full of energy. | 90

Cuvée Prestige Edizione 33 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl) (79% Chardonnay, 6% Pinot Bianco, 15% Pinot Nero; 13.14% ABV; 0.5g/l RS)

This 2008-based blend is composed of 146 plots with reserve wines from 2007 (17%) and 2006 (10%). Poured à la volée. Fresh, unblemished aromas, with orchard-fruit notes and classic Franciacorta fruit structure. All the ducks are in a row, but nothing truly stands out. | 85

Cuvée Prestige Edizione 32 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl) (78% Chardonnay, 7% Pinot Bianco, 15% Pinot Nero; 12.6% ABV; 0.7g/l RS)

This 2007-based blend is composed of 144 plots with reserve wines from 2006 (15%), 2005 (8%), and 2004 (5%). Poured à la volée. The phenolic disgorgement aromas that dominate this wine indicate that it has been opened between windows of disgorgement opportunity. Not possible to make a reliable judgment at this juncture. | NS

Cuvée Prestige Edizione 30 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl) (75% Chardonnay, 10% Pinot Bianco, 15% Pinot Nero; 12.9% ABV; 0.9g/l RS)

This 2005-based blend is composed of 134 plots with reserve wines from 2004 (15%) and 2003 (10%). Poured à la volée. An utterly gorgeous wine of timeless aging. Considering this is from a cold, wet, and delayed year that required extensive sorting, Edizione 30 is nothing short of miraculous. I have tasted this commercially disgorged, and it was not in the least bit outstanding. Obviously, it was the same wine initially, so why the difference? Natural-cork bottle variation? Disgorgement window? Clear glass? Just too many anomalies to make a call. | 95

Cuvée Prestige Rosé Edizione 44 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl)

(80% Pinot Nero, 20% Chardonnay; 12.5% ABV; 2.7g/l RS)

This 2019-based blend is composed of 16 plots with Chardonnay-only reserve wines from 2018 (10%). The grapes were destemmed and macerated for 24–36 hours, then blended with the Chardonnay seven months later. Darkish color, simple fruit… not impressed. Not produced in magnum, but if and when Ca’del Bosco moves away from clear glass, it should be. | 75

Vintage Collection Satèn 2017 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl)

(85% Chardonnay, 15% Pinot Bianco; 12.5% ABV; 0.4g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 14 plots. Severe spring frosts damaged two thirds of Ca’del Bosco’s vineyards. Harvested mid-August with peak temperatures of 102°F (39°C), yielding 4,000kg/ha and providing 17hl/ha (43% extraction). Fresh, restrained, flowery aromas, with a nice flick of toast, followed by very ripe fruit on a plush palate. Very good, but not in the same league as Satèn 2015, 2014 (magnum), or 2012 (magnum). | 90

Vintage Collection Extra Brut 2017 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl)

(64% Chardonnay, 26% Pinot Nero, 10% Pinot Bianco; 12.5% ABV; 0.4g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 25 plots. Same annual conditions, harvest, and yields as the Satèn above. Soft, toasty aromas with elegant, mouth-watering fruit on the palate. So complete and satisfying, with textbook pin-cushion mousse and the promise of slow-building complexity. Wonderful! | 95

Vintage Collection Dosage Zéro 2017 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl)

(69% Chardonnay, 18% Pinot Nero, 13% Pinot Bianco; 12.5% ABV; 0.3g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 24 plots. Same annual conditions, harvest and yields as the Satèn above. Charming, toasted-brioche aromas, with elegant fruit and fine mousse on the palate. | 90

Vintage Collection Dosage Zéro 2016 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (65% Chardonnay, 22% Pinot Nero, 13% Pinot Bianco; 12.9% ABV; 0.8g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 28 plots. Harvested in the last third of August, yielding 8,000kg/ha and providing 34hl/ha (43% extraction), this magnum won a gold medal at CSWWC 2021. Lovely, toasty layers on deliciously ripe, flinty fruit. Powerful, but linear, smart, and stylish, with nicely yeast-complexed finish. | 95

Vintage Collection Dosage Zéro 2015 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum)

(65% Chardonnay, 22% Pinot Nero, 13% Pinot Bianco; 12.8% ABV; 1.2g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 24 plots. Harvested in the second third of August, yielding 8,200kg/ha and providing 35hl/ha (43% extraction). Fresh, succulent, zesty-citrus fruit, with a very delicate mousse. This is a very good, elegant wine that has some finesse, but not the completeness, nor the degree of finesse that the Satèn of the same vintage has. | 90

Vintage Collection Dosage Zéro 2014 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (65% Chardonnay, 22% Pinot Nero, 13% Pinot Bianco; 12.5% ABV; 1.8g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 19 plots. Harvested in the last third of August, yielding 8,000kg/ha and providing 34hl/ha (43% extraction). This delicious, toasty, golden-hued beauty has come on leaps and bounds over the past 3 to 4 years. Beautiful acidity drawing a long line in the linear fruit structure, with yeast-complexed, yellow fruit and hints of grapefruit on the finish. Simply vivacious! | 95

Vintage Collection Dosage Zéro 2013 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (65% Chardonnay, 22% Pinot Nero, 12% Pinot Bianco; 12.5% ABV; 1.5g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 25 plots. Harvested in the last third of August, yielding 7,500kg/ha and providing 32hl/ha (43% extraction). Another gorgeous, toasty-rich wine. More power, less elegance, but packed with energy and freshness, therefore not lacking finesse. | 93

Vintage Collection Dosage Zéro 2012 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (65% Chardonnay, 22% Pinot Nero, 13% Pinot Bianco; 12.5% ABV; 1.7g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 25 plots. Harvested in the second third of August, yielding 7,400kg/ha and providing 32hl/ha (43% extraction). This vintage has a similar power to the 2013, but it is more linear, compressed, and intense. The restraint in the toastiness is so impressive. Such a long and lingering finish. Fabulous! | 95

Vintage Collection Dosage Zéro Noir 2013 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl) (100% Pinot Nero; 12.5% ABV; 0.9g/l RS)

Composed of wines from just 3 plots on Ca’del Bosco’s acclaimed Belvedere vineyard at at altitude of 1,500ft (466m) overlooking Lake Iseo. Harvested on September 6, yielding 5,900kg/ha and providing 25hl/ha (43% extraction). Thunderstorms and extremes of temperature reaching almost 104°F (40°C) were responsible for gray rot, requiring the strictest pre-selection in the vineyard and addition sorting in the winery prior to the full “Berry Spa” treatment. What a beautiful, rose-gold hued delight has blossomed from such an awkward start. Pure finesse, from its warm and welcoming toasty aromas, through plush fruit and velvety mousse, to its never-ending finish. | 96

Vintage Collection Dosage Zéro Noir 2011, 2009, 2007, and 2006 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl) (100% Pinot Nero; 12.5% ABV; 0.9g/l RS)

Although I am used to tasting à la volée, I found the potential of these four vintages difficult to predict, particularly in context with the awesome quality of the commercially disgorged 2013. Sometimes it is better to disgorge à la volée the day before and allow the disgorgement aromas to settle. These aromas, which should not show in the commercially disgorged wine and seldom do, can include excessively aldehydic. Maybe a future à la volée vertical could be disgorged one day ahead, but for now, I shall reserve judgment. | NS

Annamaria Clementi 2013 DOCG Franciacorta (75cl) (75% Chardonnay, 15% Pinot Nero, 10% Pinot Bianco; 13% ABV; 0.7g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 24 plots. Harvested in the last third of August, yielding 7,500kg/ha and providing 29hl/ha (39% extraction). Same weather and harvesting conditions as the Vintage Collection Dosage Zéro Noir 2013 above and, well, goodness gracious me, what a mesmerizing wine it is! Another glorious 2013, this extraordinarily fresh and vibrant Franciacorta has a refined and toasty nose with complex notes of brioche, biscuit, and bread, exquisite linear structure, and intensely rich fruit beautifully balanced by bright acidity. Full of life and vitality. | 96

Annamaria Clementi 2013 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (64% Chardonnay, 26% Pinot Nero, 10% Pinot Bianco; 13% ABV; 0.7g/l RS)

Same as the 75cl above, but disgorged à la volée and super-charged by the magnum effect to make it even more mesmerizing. Wonderfully toasty aromas cross seamlessly from nose to palate, where the fruit is silky-smooth and buoyant on a creamy mousse. Beautifully balanced. Opulence meets class! Extraordinary length. Extraordinary quality. This has to be one of the greatest Franciacortas I have ever tasted. | 98

Annamaria Clementi 2011 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (65% Chardonnay, 15% Pinot Nero, 20% Pinot Bianco; 12.9% ABV; 1.4g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 15 plots. Harvested in the middle third of August, yielding 7,700kg/ha and providing 30hl/ha (39% extraction). Poured à la volée, all these magnums of Annamaria Clementi are fabulous sparkling wines by any yardstick. Thank goodness for scores, which enable me to provide a distinction between the degrees of greatness that mere words cannot do. This is just so lovely and satisfying. It has a super-fresh, deliciously toasty nose, with fleeting notes of coffee and charred oak, followed by glacially evolved, yeast-complexed fruit over a sumptuous mousse on a classic lean structure, tapering endlessly to a finish of great finesse. | 97

Annamaria Clementi 2010 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (55% Chardonnay, 20% Pinot Nero, 25% Pinot Bianco; 12.8% ABV; 1.2g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 18 plots. Harvested in the first third of September, yielding 7,600kg/ha and providing 30hl/ha (39% extraction). What a stunning wine! Words fail me. It is just so complete and satisfying in every respect. How can a wine have so much intensity and yet practically no weight? This is masterclass in and of itself. Annamaria Clementi 2010 in magnum demonstrates that if complexity builds up slowly enough, it will not just retain fruit and freshness, but can do so in perfect harmony. Is this the greatest Franciacorta ever produced? I cannot even answer my own rhetorical question because the commercially disgorged version of this magnum was not very impressive at all in 2020. As there is no danger of clear glass involved, and Ca’del Bosco is consistently super-protective about the entire disgorgement process, it can only be whether the window of opportunity was open, and clearly it was not. | 99

Annamaria Clementi 2009 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (55% Chardonnay, 20% Pinot Nero, 25% Pinot Bianco; 12.7% ABV; 2.0g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 26 plots. Harvested in the second third of August, yielding 8,000kg/ha and providing 31hl/ha (39% extraction). This is the first vintage of Annamaria Clementi to benefit from Ca’del Bosco’s “Berry Spa” and had it not come immediately after the 2010, this wine would have been amazing. Even after the 2020, it is delicious, with just a phenolic hint to knock it down from a 95-point score. | 94

Annamaria Clementi 2008 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (55% Chardonnay, 20% Pinot Nero, 25% Pinot Bianco; 12.5% ABV; 1.7g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 29 plots. Harvested in the last third of August, yielding 7,700kg/ha and providing 30hl/ha (39% extraction). There is toast and there is toast: from the sulfidic toast, which arrives quickly and lacks finesse, to the slowly evolved toast that emerges as super-mellow notes. This has the latter in spades, and it’s so classy. Toast heaven! And the color is so pale when compared to younger vintages of Annamaria Clementi. Truly great Franciacorta. | 97

Annamaria Clementi 2007 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum) (55% Chardonnay, 20% Pinot Nero, 15% Pinot Bianco; 12.5% ABV; 1.3g/l RS)

Composed of wines from 28 plots. Harvested in the last third of August, yielding 7,500kg/ha and providing 29hl/ha (39% extraction). Complex aromas of smoke-infused toast mingle with exceptionally fresh citrus and orchard fruits, following onto a perfectly balanced palate, gently supported by a creamy-pincushion mouse. Seductive and satisfying. | 95

Annamaria Clementi Rosé 2013 DOCG Franciacorta (Magnum)

(Pinot Nero 100%; 12.8% ABV; 1.5g/l RS)

Composed of wines from just 3 plots. Harvested on August 26, yielding 7,700kg/ha and providing 35hl/ha (45% extraction). With the exception of the 2011, which won a gold medal and Best in Class at the CSWWC in 2021, the rosé Annamaria Clementi has not impressed me much. | 85

STILL WINES

Corte del Lupo Bianco 2020 DOC Curtefranca (75cl)

(80% Chardonnay, 20% Pinot Bianco; 13% ABV)

Harvested the first third of September, with a yield of 35hl/ha (from 6,000kg/ha of grapes), and just 25% of the wine was aged in one-year-old oak barriques, while the rest aged on lees in stainless-steel vats. Nice minerality of fruit. I prefer the leaner, cleaner, crisper profile of this Chardonnay-dominated wine to pure Chardonnay, although the different vintages do not make a valid comparison. A vertical of both at some future date would be instructive. | 89

Chardonnay 2018 DOC Curtefranca (75cl)

(100% Chardonnay; 13% ABV)

Harvest began on September 6, with a yield of 39hl/ha (from 6,800kg/ha of grapes). 100% fermented and aged for nine months in new oak barriques, with weekly bâtonnage and the rest aged on lees in stainless-steel vats, Too oaky, too broad, and too leesy for me. | 84

Corte del Lupo Rosso 2018 IGT Sebino (75cl) (38% Merlot, 33% Cabernet Sauvignon, 22% Cabernet Franc, 7% Carmenère; 13.3% ABV)

Harvested the second half of September, with a yield of 51hl/ha (from 8,000kg/ha of grapes). Vat-fermented in stainless-steel, gravity-fed to oak barriques for MLF, then aged in a combination of oak and stainless-steel. Plenty of black fruits, but a touch of bitterness, and too much oak on the mid-palate through the finish. | 89

Maurizio Zanella 2018 IGT Sebino (75cl)

(50% Cabernet Sauvignon, 25% Cabernet Franc, 25% Merlot; 13.5% ABV)

Harvested between September 21 and 25. Vat-fermented in stainless-steel, gravity-fed to oak barriques for MLF (70% new) and 13 months aging. This was Annamaria Clementi’s favorite, and frankly, it’s mine, too. I would have loved to share a glass of this lovely blend with her. Deep ruby color that is beginning to mellow, rich in soft black fruits, particularly blackberry with a touch of blackcurrant, with spices, first mace, then nutmeg, and finally notes of cinnamon infused by the oak. Nice and grippy finish. | 92

Pinéro 2019 IGT Sebino (75cl)

(Pinot Nero 100%; 13.5% ABV)

Harvested on August 22, with a yield of 35hl/ha (from 6,000kg/ha of grapes). Vat-fermented in stainless-steel, gravity-fed to oak barriques (50% new) for MLF and 11 months aging. Although a lovely, elegant wine in itself, it lacks true Pinot expression and could benefit from 10–20% carbonic maceration—not to show the slightest amylic aroma, but simply to lift the varietal character, much as many Australians did in the 1980s before they understood how to grow and produce classic Pinot Noir for themselves. | 89

Carmenero 2018 IGT Sebino (75cl) (100% Carménère; 13% ABV)

Harvested on September 25, with a yield of 41hl/ha (from 7,000kg/ha of grapes). Vat-fermented in stainless-steel, gravity-fed to oak barriques (65% new) for MLF and 12 months aging. There are wolves all over Ca’del Bosco’s roof and, as the label for this wine depicts, Carmenero is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. This is because the vines were purchased in 1990 by Ca’del Bosco as Cabernet Franc (it is, after all, a Cabernet Franc × Trousseau cross, and the same error has been made as far afield as New Zealand) but were later identified as Carménère. This vintage has a full ruby color, with chocolate and balsamic oak aromas on the nose. The palate has bright black fruit, particularly blackberry, with plums and fresh, toasty oak, complexed by notes of vanilla and grilled coffee beans. | 89

Merlot 2009 IGT Sebino (75cl) (100% Merlot; 13% ABV)

Harvested on September 15, with a yield of 50hl/ha (from 8,700kg/ha of grapes). Vat-fermented in stainless-steel, gravity-fed to oak barriques (65% new) for MLF and 11 months aging. Not regularly produced, this vintage is remarkably fresh for 13 years, with a nose of ripe plums and fleeting glimpses of violets and warm baking spices. Soft and fruity with supple, ripe tannins and a kick of acidity to maintain freshness on its long finish and lingering aftertaste—even staunch supporters of Miles in Sideways should give this wine a try! | 91