If wine is not art in the way that, say, painting, music, and poetry are art, it thrives somewhere in fine art’s hinterland. Wine is less complex in origin and effect than art (though often more delicious), and there are other reasons for keeping it in the more modest category of agriculture. Nonetheless, wine lovers persistently feel compelled to invoke aesthetic categories such as beauty and harmony, and the ideas expressed in this speculative and exploratory essay are in that tradition.

Without pushing an identification with fine art too far, there is validity — and certainly usefulness — in wine criticism borrowing the term “kitsch” from the aesthetic realm (even if it is not much easier to characterize this more precisely than many other aesthetic terms). Conceptualizing kitschiness in wine can bring a new coherence and a fuller understanding to our experience of the past half-century of wine production, precisely through linking it to a larger socio-aesthetic experience. Kitsch elements in wine that will be adduced here include inappropriate fruitiness, oak flavor, and sweetness — characteristics analagous to, for example, overt sentimentality in kitsch literature and painting. Problematizing these vinous phenomena is by no means new, but taking them from the shifting categories of idiosyncratic preference or untheorized elitism and thrusting them into a wider sociocultural pattern can add to our understanding of what has happened in the modern world of wine.

It should be made immediately clear that the primary focus of this essay is not the visual kitsch evident in the packaging of many wines (the “critter” phenomenon being a recent egregious and, occasionally, charming example). Rather, it is kitsch wine itself that needs discussion – although, of course, there is more often than not a correspondence between wine and label.

Wine kitsch appears to be a much more recent development than kitsch in the fine arts. The origins of the word are unclear, but Whitney Rugg says that it “first gained common usage in the jargon of Munich art dealers to designate ‘cheap artistic stuff’ in the 1860s and 70s” and caught on internationally in the early decades of the 20th century.1 This historical timing is significant in terms of socioeconomic developments. The art critic Clement Greenberg –whose historically important and still-resonant essay of 1939, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” I have plundered for my own title, as well as for inspiration — argues plausibly that kitsch “is a product of the Industrial which urbanized the masses of Western Europe and America and established what is called universal literacy.”2 Formal culture (Greenberg’s distinction from a rural, localized folk culture) had previously been largely confined to a leisured, cultivated elite; a new market arose for an “ersatz culture” for those lacking “cultivation” but “hungry nevertheless for the diversion that only culture of some sort can provide.”

The emergence of kitsch in wine

This formulation is easy to translate into wine terms, but there’s an important difference to be noted. For in a sense, there was already some “universal literacy” with wine, in much of Western Europe anyway, prior to the Industrial Revolution, and this is paradoxically one of the reasons kitsch wine only emerged later. There was undoubtedly a wine elite: The claret and hock that gentlemen sipped in their St James clubs were a world away from the wine (or piquette) from which the Sicilian peasant and Parisian proletarian derived useful calories and, let’s hope, numbing respite from the harshness of their lives. Nonetheless, they were all drinking wine. Some of it was very good (almost entirely at the expensive end of the continuum, of course), and much of it, no doubt, was extraordinarily bad in modern terms, as is pointed out frequently by those commentators who unproblematically claim we are living in the golden age of wine.

In 1850, the difference between mass art and “authentic” art was already one of kind rather than quality alone: There was now kitsch, too, as opposed to “genuine” culture. With wine, any difference was more simply a matter of quality. The local wines that were drunk by the poor were roughly analogous with folk art, which is not kitsch when it is produced and consumed appropriately and authentically, especially in rural areas. But everywhere the wines of “the masses” were more analogous to genuine art (folk or cultivated) than to the industrialized art increasingly fed to the urban working class and petty bourgeoisie, and to the somewhat superior kitsch available to the new and often rich “upper middle-class” — that is, they retained a genuineness, an authenticity (however awful), and a pre-industrialized essence that meant they were not kitsch.

In a sense, then, with wine, there was a growing mass market without mass production. This was doubtless because no one had worked out how to mass-produce wine in a satisfactory or profitable way. Even more significantly, there were as yet no strategies to create new markets outside the traditional consumer groups (which in wine-producing countries included almost everyone; elsewhere, the alcoholic drink of the poor, at least, was beer or spirits), because it was precisely these new markets that were the markets for kitsch products. Furthermore, there was an established market for large volumes of wine produced locally – even if the definition of “local” changed somewhat with the development of the railways.

It is worth pointing out here, when referring to the crucial difference between the categories of quality and kind, that if kitsch in art, music, and literature arose at the mass-production level and was largely directed at the urban poor and middle classes, it very soon started creeping up the social scale, especially as the traditional heights were dismantled and reconstituted. Part of the problem of identifying kitsch — a problem particularly for the insecure consumer anxious to avoid it, but without the access to hegemonic values that “cultivation” brings — is precisely in this transmigration of kitsch into technically high-quality and certainly very expensive products. I shall return to this later, because the relevance to wine is depressingly clear.

No doubt the blending and branding of cheap wine for large traditionally wine-consuming markets, such as in Paris, had been growing for decades, but the emergence, on an international scale, of mass-produced wine in the more industrialized sense, and with it the emergence of kitsch wine, can probably usefully be dated to the early success of Sichel’s Blue Nun Liebfraumilch in Britain in the early 1920s.3 Whether Blue Nun was kitsch at that stage, I don’t know; but it became so at some early stage of its long and as-yet-unfinished history, though more recently it has been aiming to reclaim respectability. In those early days, however, production was small by today’s standards: By 1930, the applauded huge volumes of Blue Nun sold annually in the UK amounted to little more than 1,000 cases, according to the brand’s website (www. bluenunwines.com). This number was to rise to 3.5 million bottles in the 1970s and yet higher later. Significantly, Blue Nun’s label became more kitschily sentimental in its appeal as it sought, and claimed, larger and larger markets.

It was, indeed, only after World War II, especially with the liberation of the North American wine drinker and the longing of Northern Europeans for sweetness that the relentless mass marketing of wine began, and it was predicated on kitsch wine. Mateus Rosé is a famous example. Inspired by authentic, naturally frizzante red and white Vinho Verde, but sweetened, and with its pretty color carefully managed, it was created as early as 1942 and styled to appeal to the unsophisticated new markets in the United States and the UK particularly; in the following decades, production grew rapidly — to unprecedented heights.

The kitschiness of the wine is primarily expressed in its soft, facile sweetness and its mildly amusing pétillance. As far as the USA is concerned, it is widely accepted that the mass consumption of “soda pop” there dictated the level of residual sugar of popular wine. Perhaps, but it is unnecessary to infer consequence; it would be plausible to suggest that the tastes of the dominant mass market in Anglo-Saxon countries were met in both soda pop and wine by the easy gratification of sweetness. Beaded bubbles winking at the brim helped.

Several other big brands of kitsch wine date from the postwar period, a time of great economic expansion and vast extension of consumer markets. Lancers, for example, provides a neat illustration of a unity of form and content — its spurious earthenware crocks provided for surely as many kitsch candle-holders as did wickerwork Chianti fiaschi. As with mass production in other spheres of economic activity, scientific understanding and technological developments, notably controlled-temperature fermentation, were important components. Cool ferment in stainless steel allowed “German-style” white wines to be made for a new market, as far away from traditional Europe as South Africa; and for some time in the 1970s, a semi-sweet Cape wine called Lieberstein was apparently the biggest-selling wine in the world (with more than 5 million imperial gallons produced in 1964).

The 1970s also saw the multimillion-case success story of fizzy, semi-sweet Riunite Lambrusco in the United States. Another quintessentially kitsch style, California “blush” Zinfandel was prefigured when Sutter Home Winery released its White Zin in 1973; the pink-tinged and off-dry style came in 1975. Even before Australia brought the world the delights of sunshine in a bottle, everywhere — from metropolis, to colony — was now reveling in huge volumes of kitsch wine: wine designed with a market and price in mind, and manufactured on an industrial scale, appealing to the simplest values of wine pleasure — sweetness and overt simple fruitiness, as well as alcoholic comfort and buzz.

Kitsch in context

One counterexample (though hardly sobering) to my suggested kitsch timeline might be Champagne. Before the end of the 19th century, it had already established itself as the wine of conspicuous consumption for the nouveaux riches of Europe and America and for the decadent aristocracy of Russia. Moreover, Champagne was, at that time, predominantly sweet; but it is probably the social significance of Champagne, as well as its inherent showiness — all that froth encased in all that elaborate packaging — that has made it always vulnerable to accusations of kitschiness. This vulnerability continues today, despite Champagne’s unquestioned and frequent moments of sublimity. Some theorists suggest that the way in which a cultural work is consumed can turn anything into kitsch — so that Matei Calinescu identifies kitsch in “a real Rembrandt hung in a millionaire’s home elevator,” saying that a determination of kitschiness “always involves consideration of purpose and context.”4 When a racing driver sprays his fans with Moët, that seems pretty obviously kitsch. Is Roederer Cristal kitsch when flashed around by rich hip-hop artists and, depending on the color of one’s snobbery, when flashed around by rich hedge-fund dealers in a smart restaurant, but definitely not so when discreetly and appreciatively sniffed by an elegant wine critic? Such questions, while valid and important, do take us away from the wine itself. Moving into this sort of speculation would necessitate articulating a complete position on the intersection of the aesthetic aspect, with the social significance and class origins of the ideas of vulgarity, good taste, elitism, and suchlike complexities — something best avoided here, where we can separate out kitsch behavior and largely concentrate on the contents of the bottle.

So, then, we must ask: If commercial Liebfraumilch is identified as inherently kitsch, what of a traditional Mosel Kabinett, delicately fruity, fragrant, and off-dry? Is it just a quality difference it usually obtains that saves the latter from being kitsch? No; the thrilling balance of fruity sweetness and acidity in a good Mosel itself makes the difference — more one of type than of quantity. In the Liebfraumilch, which I’m picking on so relentlessly, it is the sweetness and the fruitiness that are the real content of the wine, as it were, and the locus of its kitschiness; in the Kabinett, it is the knife-edge balance that defines and adds a welcome element to the pleasure of drinking. Kitsch wine has no challenge or excitement, only easy gratification, and confirmation of expectation. Moreover, the context is one of authenticity: The Mosel wine is made this way as a genuine expression of its (agricultural) origin.

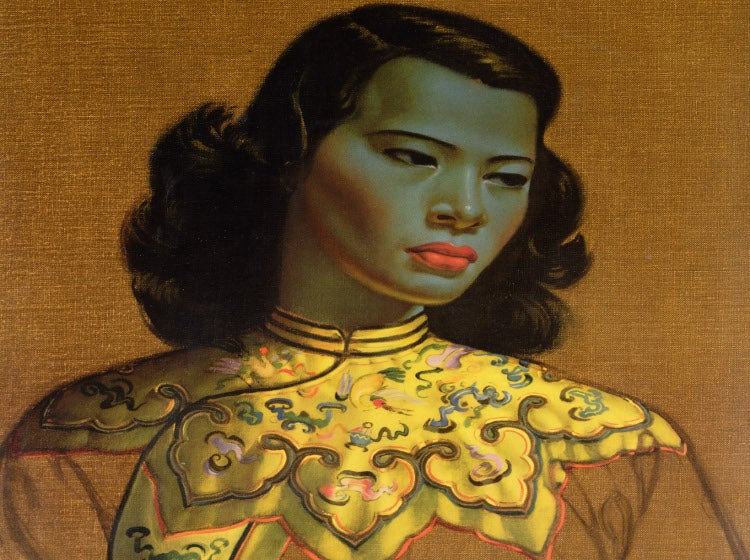

This example indicates an essence of what makes wine kitsch. In painting, the sweetness of a Raphael Madonna can be extracted from the complexity and artistry in which it exists (and that includes, but is not limited to, technical mastery) and transferred (so easily and so often!) into the simplistic, simpering sentimentality of a kitsch equivalent. The kitsch version can, of course, also be technically proficient, but even the technique is transformed by the ends it is serving; usually, it is as formulaic as the content. So, too, as with abstracted Mosel sweetness (and fruitiness in simpler young wines), we have the reification of other characteristics — of the pétillance of Vinho Verde, or of the suggestion of oak-assisted complexity in fine Bordeaux, for example — and their application in other wines as ends in themselves, attributes of cellar technique rather than essential components of terroir and the authentic historical development of related winery practices — at which point the wines become kitsch. Analogously, Robert C Solomon, in his essay “On Kitsch and Sentimentality “, suggests, “Kitsch is art [whether or not it is good art] that is deliberately designed to move us, by presenting a well-selected and perhaps much-edited version of some particularly and predictably moving aspect of our shared experience.”5 Predictability and meeting predictable requirements through formulaic manufacturing techniques are essential elements of kitsch in wine.

With wine, just as with the arts, once the marketability of kitsch directed at the masses has become clear, an upmarket movement becomes inexorable. Contemporary forms of democracy have not, of course, done away with social elites bound up with wealth, even if they have largely eliminated that fixed “leisured, cultivated elite” to which Greenberg referred. The ranks of the very rich and the merely rich are continuously refreshed by those without “cultivation”; and the market so demands easy access and so resents the “refinement” that comes primarily with education and experience that those qualities are even sneered at selectively by the general social culture (hence all those accusations of “wine snobbery” and so on in our case, to the point where the serious wine lover is beleaguered and rendered defensive). This all means that at the “upper” levels of wine consumption, too, there is a demand for kitsch wine. Because most of the consumers — and that noun is totally appropriate here — need to believe that this is not an ersatz product and are willing to pay for the assurance, it must be presented in the traditional way (though merely putting a high price to something often suffices to convince such victims of that thing’s quality).

So, it is not only at the “mass” end of wine production that we find easily ingratiating sweetness and fruitiness. It creeps into “serious” and expensive wines, either by ultra-ripeness and higher alcohol levels or simply by the manipulation of the amount of residual sugar in a wine. Examples of such wines are legion among, for example, California Chardonnay and Australian Shiraz. The increasing demand for the fruit flavors and the soft textures of ripeness in “serious” wines is not very different from the demands put on “commercial” wine for easy gratification. It’s not simply a question of this level of wine not being cellared for as long as it used to be. The quality of tannins widely sought now is not the same quality as that of more traditional tannins “softened” by maturation in bottle; I suspect that the velvety modern young tannins, some of which I would call kitsch, are widely preferred to older ones bearing an inherent reminiscence of austerity. The flavoring of some cheaper wines with wood chips is essentially no different from the flavoring of much more expensive Napa Cabernet (and Bordeaux) with new-oak barriques. In both cases, the aim is to provide a decontextualized, easily recognized index of quality and of a spurious spicy, mocha, vanilla charm. This is analogous to the “automatic, and therefore unreflective, emotional reaction” that is triggered by “highly charged imagery, language, or music” of the kitsch kind, according to some theorists, says Rugg.

In search of the avant-garde

Kitsch wine, like kitsch art, must necessarily be conservative, given its reliance on the commonplace and the established and its evocation of stock, easy responses from consumers. It is interesting, therefore, to consider the applicability to wine of Greenberg’s notion of the avant-garde in art (even though this notion is less appropriate nowadays). His essay can be seen, in fact, as being primarily concerned with the defense of this concept; he deals with kitsch as the pervading condition of the contemporary world’s ersatz culture, against which avant-garde art should be seen effectively as a protest. What the serious artist in modern industrialized society was driven to, says Greenberg in 1939, is “abstract” or “non-objective” art that makes art itself the subject matter and “imitates [in the word’s Aristotelian sense] the disciplines and processes of art and literature themselves.” Surrounded by a market creating a mass audience that is obliged to find satisfaction in the easy and the second-rate, where subject matter and worn-out languages prevail, the genuine artist has turned, in search for the absolute, to the very medium of art. Greenberg says, “The avant-garde poet or artist tries, in effect, to imitate God by creating something valid solely on its own terms, in the way nature itself is valid, in the way a landscape — not its picture — is aesthetically valid.”

Can we find avant-garde wine growing that is consciously in reaction to kitsch, or to the conditions that produce kitsch, by austerely refusing to invoke any of the processes that have given rise to the fetishized effect of kitsch wine? Or avant-garde wine production that is the equivalent of “abstract” art? Surely we can, but first let us note with relief that the self-conscious, and possibly cynical, postmodern appropriation by fine artists of kitsch is something by which wine lovers do not have to be troubled: Wine has not yet learned to be ironic or to be able to claim some sort of irony when it exploits the attractiveness or charm of kitsch.

Wine parallels avant-garde art in two overlapping areas – and it is not insignificant that the prime contempt of the avant-gardists would probably be directed less at mass-produced stuff than at some of the highest reaches of “commercial” wine expressly designed to appeal to a market (murmur Bordeaux, if you wish – they do!). The two sets of vinous avant-gardists would be, first, those who focus fiercely on terroir and, second, those who focus on “natural” winemaking. (Some would also refer to the biodynamists here, but I would include them as a mystical fringe of the terroirists, making their own eccentric sense of things.) The rigorous pursuit of terroir expression is, happily, well documented and familiar. David Harvey wrote recently in his column on natural wine in WFW 31 of “purists” who “dream of the grape, the whole grape, and nothing but the grape, for white and red alike: nothing added, nothing taken away.” Swartland wine grower Craig Hawkins prints on the labels of his orange wine Testalonga El Bandito, laconically and with just a little irony, “Made from grapes” — the “only” is implicit (and he could well have added “and time”). This is close in spirit to painters whose subject matter is paint and color, and the surface of the canvas; poets who write about words and writing, and the moment of poetic creation; and musicians who compose with the purest noise and with silence.

It is important, of course, to note that there is a large occupied ground between kitsch and the avant-garde in wine, though I wonder if Greenberg believed this of art in 1939. I am certainly not suggesting that the avant-garde is the sole repository of high value — though a focus on terroir is now pervading, at least rhetorically, all serious or ambitious winemaking. In fact, of course, a concern for terroir has been a long tradition in wine, one that modern market conditions have significantly weakened. The avant-garde is, precisely, reclaiming old values. I suggested that kitsch is always conservative. But in fact, the radical avant-garde in the world of wine is so thoroughly conservative — reactionary, even, in its return to traditional viticultural and vinicultural approaches and practices — that it challenges fundamentally the superficial conservatism of kitsch.

Somewhere here we can discern an important difference between wine and art. In the Greenberg formulation I quoted, he cited natural things as the “aesthetically valid” model for avant-garde art, and that seems to me to imply a correct opposition. Even the most “real” or “authentic” wine is not exactly “natural” but is a human expression of nature –potentially artistic. But crucially and inevitably, it is an expression of nature, a humanly directed expression of natural processes rather than of human processes. Wine is not art but agriculture — that is, rooted in the infinite variety that plant, soil, slope, and sun can produce in conjunction with human effort and ingenuity. Merely that — but what could be more profound? To claim that wine is art is primarily to protest at how much of it has been turned away from agriculture into industry, commodified. Nonetheless, wine’s distance from art is not great, and it has qualities and aspects in common with art. Let us retain the concept of Beauty — along with some other usefully illuminating aesthetic categories, like kitsch — in our understanding of wine. Terry Theise has suggested that “wine is music in the form of water.”6 He’s not making my point at all, but it is a lovely formulation to steal, with its allusive mystery and ambiguity, given the inartistic naturalness of water and the human labor inherent in music and wine.

Notes

1. Whitney Rugg, “Kitsch,” The University of Chicago, Theories of Media, Keywords Glossary (2000); online at https://csmt.uchicago. edu/glossary2004/kitsch.htm

2. C lement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Partisan Review 6 (1939), pp.34-49. The article has been widely anthologized and can be found at www.sharecom.ca/greenberg/kitsch.html

3. A s an illustration of this, I can refer to a quotation I used in my article “Maigret and the Case of Sauvignon Blanc,” WFW 17 (2007), from the novel Maigret et le Corps sans Tête by Georges Simenon. Inspector Maigret notes the unusually good quality of a white wine in a working-class bistrot, and the narrator continues: “It was true. Most Parisian bistrots offer a ‘simple country wine’, but more often than not it is a commercial blend [vin traffiqué] straight from Bercy. This one, by contrast, had an aroma of terroir.” Bercy was, from the late 19th century until the 1960s, the location of the Paris wine trade’s depots. Even as late as this novel, 1955, there’s no suggestion here that such commercial blends within France were inevitably kitsch wine — just comparatively poor quality and losing authenticity.

4. Matei Calinescu, Faces of Modernity: Avant-Garde, Decadence, Kitsch (Indiana University Press, Bloomington; 1977).

5. Robert C Solomon, “On Kitsch and Sentimentality,” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 49 (Winter 1991), pp.1-14.

6. Terry Theise, Reading Between the Wines (University of California Press, Berkeley; 2010).