Reading the eighth-century Tang poet Li Bai reminds us that thoughtful solitary wine-drinking can transcend the shameful or desperate connotations it has in the West, says Stuart Walton.

Not every use of wine is convivial. For all that we are accustomed to thinking of it as the agent of amity and fellowship, it has also played the role of sustenance to the solitary in literary and spiritual tradition. The image of the lone drinker had become an icon of ruin by the late 19th century, the era in which alcoholism had begun to be medicalized in the West. Between the thousand-yard stare of Degas’ abstracted absinthe drinker and Hemingway’s solitary bottle of Margaux, there is only the temperamental variance of quiet despair or reckless abandon. They are both telling us that drinking for oneself is a vice, calling forth either reflective guilt or the determination to dispense with guilt.

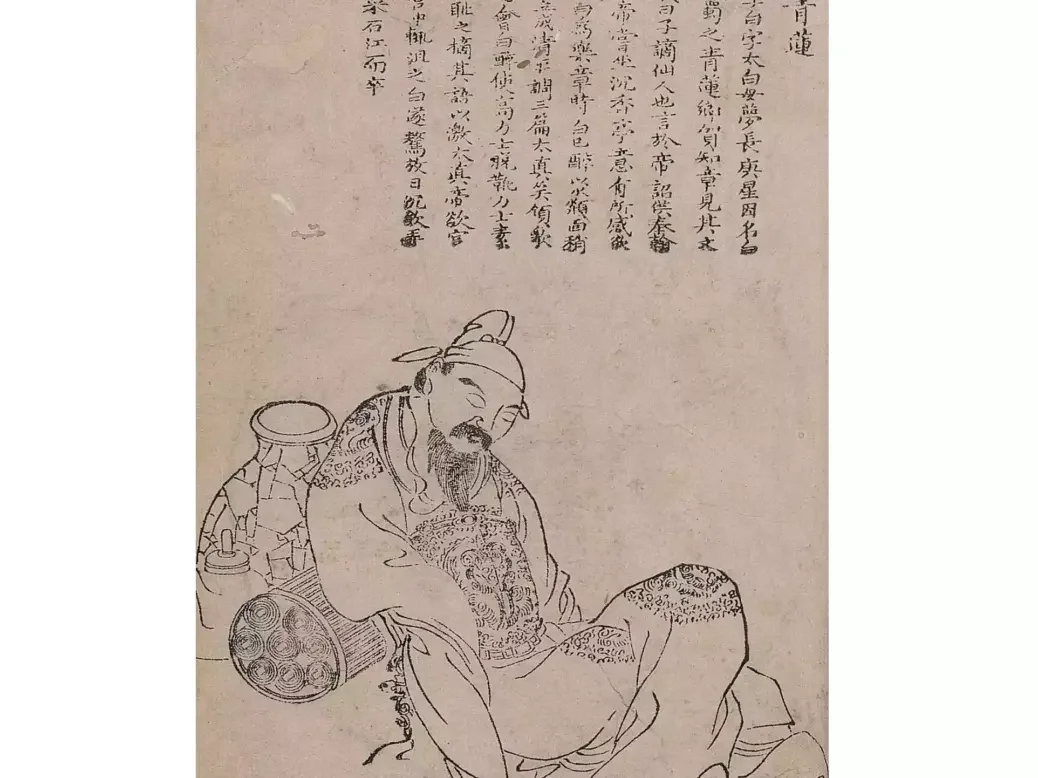

In the Chinese poetic tradition, wine is the boon companion of the solitary, the means by which he is lifted out of the melancholy present and into the transcendent sublime. The preeminent laureate of drinking alone is the Tang poet Li Bai (AD 701-762). Li Bai was probably born in Suyab in what is now Kyrgyzstan on the ancient Silk Road that connected China with Central Asia and routes to the West. His family were most likely merchants and seem to have undertaken a move to Jiangyou in Sichuan when Li Bai was a small boy. He was a gifted child, well-versed in the literary classics and already a practising poet before he was ten years old.

Had he taken the formidable civil service examination for which aspirant families prepared their more promising sons, he might have gone on to a career in amply rewarded officialdom. Instead, he was something of a loose cannon, a keen swordsman with a pugnacious bent and a serial marrier of well-connected women. In his mid-twenties, he set off on a riverine odyssey that would take him along the Yangzi and Yellow Rivers, taking the measure of a society in the throes of explosive social and cultural ferment, garnering the experience that would later return to him in moments of bibulous reflection in the great lyrics.

Drinking alone with Li Bai

Li Bai’s most widely anthologized composition, “Drinking Alone by Moonlight,” finds the poet soliciting a compact with the moon to transform his solitary session into a drinking companionship, in which his own shadow will make up a third, but in vain. “The moon, alas, is no drinker of wine; / Listless, my shadow creeps at my side.” Just him then. “Yet with the moon as friend and the shadow as slave / I must make merry before the Spring is spent.”[1] They were united when he was sober, but in drunkenness each goes his way. Even his shadow “tangles and breaks” as it tries to follow his inebriate dancing.

Springtime is the eternal season of the drunken poet. Not only is it when the fruit trees that might have flavored last year’s wine are in blossom, but it is also when the wine is at its best to drink. By the eighth century, wine (the preferred translation of the catchall term jiu) was a vastly varied product. It could be the potent multi-grain brew that had been produced since antiquity. It could be the fruit wine of peaches or plums. It might be an aromatized medicinal potion, full of floral and herbal extracts for balancing the drinker’s qi. It could be imported grape wine from the Central Asian trade routes, or even a variant of the same region’s koumis (fermented mare’s milk).

It doesn’t matter what it is. The important thing is to drink. “I urge you not to refuse a cup, / for the spring wind has come to laugh at us.” (“Facing Wine”). The trees are in blossom again, and here comes another old friend. “Bright moon peers into the golden wine cup.” He sees “[t]he rose-cheeked lad of yesterday,” now whitening with the years. We are at the opposite end of the spectrum here to drinking to forget. Wine is the sacrament of memory. “If you do not drink the wine, / Then where are the men of yesteryear?”[2]

In her illuminating gloss on this piece, its translator Paula Varsano notes that Li Bai acknowledges “both the obligation to the past and its intrinsic absurdity.” Drinking is a spiritual duty and a way of respecting both the literary tradition and one’s own past existence. “If you find happiness in wine / Don’t share it with the sober,” he warns elsewhere.[3] In “Hard is the Way of the World,” a more gather-ye-plum-blossoms mood takes hold: “Enjoy a cup of wine while you’re alive! / Do not care if your fame will not survive!”[4]

Li Bai’s fame did survive. He died at the age of 61, most likely being cared for by friends, most likely of a racketing life. In the kind of popular legend that has a forsaken duty to be true, it was said of him that, out on the lake one night in his own bateau ivre, he leaned over the water to try to catch the reflection of the teetotal moon that had accompanied so many of his nocturnes of solitary drinking. As ever, it slipped his grasp.

Notes

1 Trans. Arthur Waley, More Translations from the Chinese (London: 1919).

2 Trans. Paula M. Varsano, Tracking the Banished Immortal: The Poetry of Li Bo and Its Critical Reception (Honolulu: 2003).

3 Trans. Charles Kwong, in Scribes of Gastronomy, eds. Isaac Yue and Siufu Tang (Hong Kong: 2013), cited (and slightly modified) in Thomas David DuBois, China in Seven Banquets: A Flavourful History (London: 2024).

4 Trans. Witter Bynner, The Jade Mountain: A Chinese Anthology (New York: 1929).