The simplistic view of the French Revolution is of a period of chaos and extremism, but that was far from the full picture, says Rod Phillips, who argues that the years post-1789 were a time of era-defining progress for French wine.

The French Revolution produced a shocking story involving wine. After war broke out between Revolutionary France and other European states in 1793, the French government raised a massive army of volunteer soldiers—too many to be housed in existing barracks, so that thousands had to be billeted in private homes. Their hosts, who were reimbursed the costs of lodging them, were instructed to provide these soldiers not only prescribed measures of bread and meat, but also wine, beer, or cider—whichever was the region’s main production.1

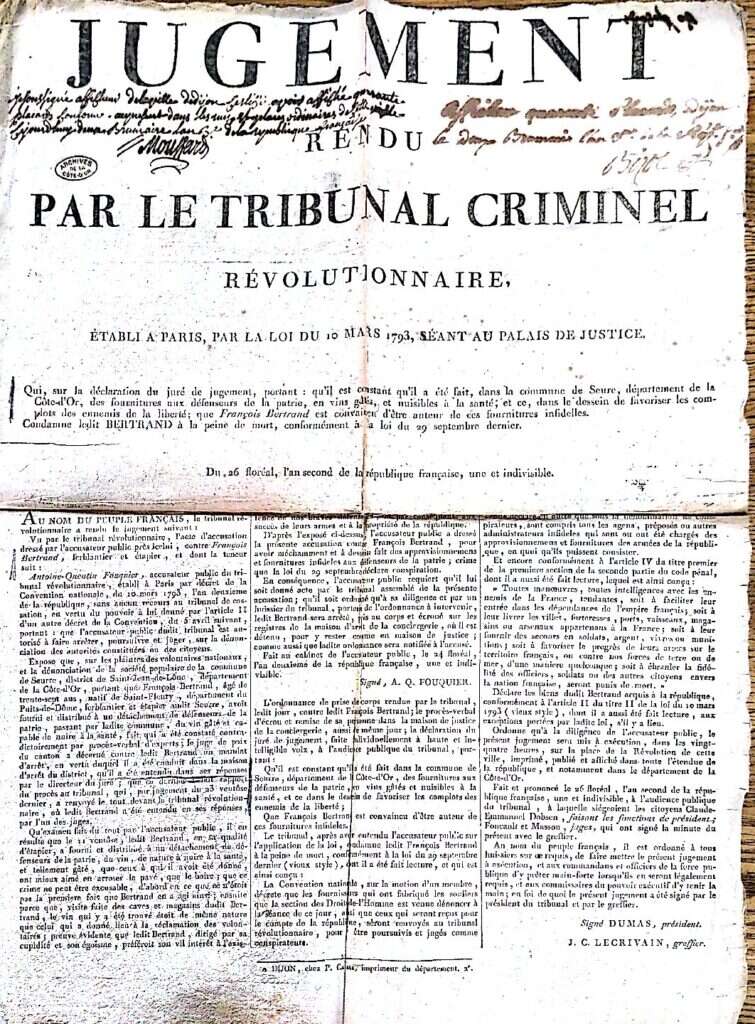

In the autumn of 1793, François Bertrand, a tinsmith in Seurre, a village in Burgundy about 18 miles (30km) east of Beaune, was billeting a detachment of volunteers. One day, he served them wine with their meal, but the wine was spoiled (gâté)—so badly spoiled that the soldiers declared they would rather “irrigate the earth with it than drink it.” They took their complaint to a nearby patriotic Popular Society, which called in expert tasters (experts dégustateurs) to assess the quality of the wine. These tasters determined that it was “of a nature to be harmful to health.”

It’s not clear what was wrong with the wine. Eighteenth-century wines were not what we would think of as delicious; from what we know of winemaking at the time, the results must often have been variously oxidized, maderized, and tainted by dirty vats and barrels. (Beware of any modern wines said to have been made in the “traditional” way!) Even given contemporary taste preferences, many wines might have been unpleasant to drink, yet they were not harmful to health. Despite that, wines were often evaluated in terms of their supposed effects on health, and the assessment of the expert tasters was that this particular wine was harmful—which tells us that it must have tasted quite foul. There is no indication of the wine’s provenance, but it was undoubtedly local, a vin de Bourgogne of some sort, and probably made from Gamay—not because Gamay wines were bad, but because they were less expensive than Pinot Noir.

Having received the tasters’ report, the Popular Society thought this case was serious enough to refer it to the Tribunal Criminel Révolutionnaire in Paris, the court that dealt with political crimes and that handled many of the famous cases during the Terror, including the trial of Marie Antoinette. In May 1794, as the Terror was intensifying, François Bertrand was tried for serving bad wine to the soldiers. This act, the judges declared, showed Bertrand’s “greed and egoism, putting his own vile interests above the wellbeing of our brave soldiers and, by extension, jeopardizing their success in battle and the survival of the Republic.” Bertrand’s action, they added, had given aid to “the enemies of liberty.” By this relentless logic, serving bad wine to soldiers was an act of treason. Bertrand was sentenced to death, and the guillotine ended his life soon after. We might say that the Revolutionaries took their wine seriously.

This story checks some of the boxes widely associated with the French Revolution: kangaroo courts, arbitrary executions, irrationality, and extremism. But that is very far from a complete and accurate picture, because, if we focus on wine—and in this article we will look particularly at Burgundy—we can see that the French Revolution was a very constructive period. It broadened the ownership of wine production, encouraged better vine management and winemaking, made wine accessible to more French people, strove to improve wine quality, and embedded wine in French culture. In short, the French Revolution established some of the bases for the French wine industry and the place of wine in French culture for more than a century afterward.

Before the Revolution, French wines were, as they are today, starkly stratified by quality. The bulk of the population—peasants, manual workers, and artisans—drank mediocre or poor-quality wines known as vins communs or vins pour boire. These were generally produced close to the markets where they were sold and consumed. “Buying local” wasn’t a moral exhortation, however, but a simple financial imperative, because shipping wine any distance added considerably to the price.

The price of wine was less important to better-off people, of course. Nobles and well-off merchants and professionals could afford to drink the higher-quality wines known as vins fins or vins de cru. If they lived in regions such as Bordeaux and Burgundy, which were already known for their superior wines, they could often buy very sound or excellent wines at reasonable prices because they were locally produced. Those with substantial means could also afford wines produced elsewhere in France and throughout Europe, despite the extra fees incurred. Inventories of the cellars of wealthy households in the decades before the Revolution show hundreds of liters of wine—in bottles and barrels of various sizes—from the prestigious regions of France and elsewhere.

In Burgundy, the cellar of the Duke of Tavanes was mainly stocked with wines from Burgundy and the Médoc, as well as from Hungary and Cyprus. The cellar of the first president of the Parlement de Bourgogne held mostly local wines, many from prestigious vineyards such as Chambertin, Clos de Vougeot, and Montrachet. The Duke of Ponthièvre had a massive cellar that included wines from Burgundy, Bordeaux, and Champagne, and also from Spain, Italy, Germany, and Cyprus.2

Wine, like other commodities, reflected the social hierarchies of Old Regime France. At one end, peasants and workers drank poor wine, ate gruel and coarse dark bread, and dressed in clothes made from serviceable fabrics such as cotton and linen. At the other, the elite drank fine wines, ate refined white bread and other delicacies, and wore clothes made of expensive materials such as silk and lace. Such distinctions came under attack as various Revolutionary administrations tried to level society. Citizens—everyone became a citoyen or citoyenne, as titles such as Sieur and Madame went out of fashion—were to drink affordable, good-quality wine, eat bread that was somewhere between refined white and coarse brown, and dress in modest clothing. Wine thus became one of the symbols of social and political change in Revolutionary France, and it is not surprising that governments paid attention to it.

Rich ecclesiastical pickings and fragmentation

The first major impact of the Revolution on the nation’s wine resulted from one of the most important decisions made during the Revolution: the seizure of the assets of the French Church in 1790. As part of a reorganization of the Church, all property not needed for purely religious purposes—that is, churches where masses and other religious events, such as baptisms, took place—was decreed to be “property of the nation” (bien national) and was to be sold to private individuals. Sale would be by auction so as to maximize prices paid, and the money raised would be used to pay down the massive debt left by the monarchy, which had bankrupted France by the 1780s. Rather than repudiate the debt, the new Revolutionary legislature recognized that selling off Church property would bring in millions of livres (French pounds). The property in question—which included religious houses, supernumerary churches, and agricultural estates and their buildings and equipment—accounted for about one tenth of France’s land.

This land included thousands of hectares of vineyards, together with cellars, wine presses, and barrels. Some vineyards were owned by large religious houses, such as the Cistercians; by 1789, they owned about 2,000ha (5,000 acres) of vineyards in Burgundy, including vines in some of the most prestigious districts, such as Vougeot and Corton. Other Church-owned vineyards included the modest holdings of individual parishes throughout France, often a few rows of vines scattered among a number of parcels. In Volnay, the parish owned, and the priest derived income from, about 0.66ha (1.5 acres).3

Although there was no explicit intention to reconfigure the French wine industry (if we can call it that), the effect of the expropriation of Church vineyards was to end the centuries-old role of the Church in wine production. We do not know what proportion of French wine was made by Church entities and what proportion by secular owners before the Revolution, but it clearly varied by region. The Church played a much greater role in wine production in Burgundy than in Bordeaux, where the nobility was far more involved. But the sale of vineyards was countrywide, because religious houses, cathedrals, and parishes throughout France owned vines that were no longer considered necessary for the Church to function as a stripped-down institution concerned solely with spiritual matters.

The auctions resulted in money flowing into the state coffers. Wine was clearly regarded as a good investment, and all the expropriated vineyards seem to have fetched prices above the valuation that had been placed on them. Some sales showed modest premiums, such as 0.2ha (0.1 acre) of vines in Monthelie, which was valued at 500 livres and sold for 670 livres to an inhabitant of the village. Other lots did much better. Some 25ha (62 acres) of vines and some other land, together with buildings, cellars, and presses, all seized from the Abbey of Cîteaux, were bought by a royal notary from Paris for 150,100 livres, more than twice the 68,587-livre valuation.4 Meanwhile, the 0.66ha (1.5 acres) of vines owned by the parish of Volnay were assessed at 1,883 livres and sold for 6,125, more than three times the valuation.5

The premiums paid for vineyards undoubtedly reflected their perceived future value. The wines of Volnay, for example, were among the most expensive in Burgundy, and half the parish’s parcels of vines were located in vineyards later designated premier cru. The successful bidders were largely urban professionals and merchants (in Champagne they included Jean-Rémy Moët, later of Moët-Hennessy, who acquired expropriated Church land to increase his holdings) or wealthier peasants who already owned vineyards. The collective result of these auctions was that, by 1793, virtually all French wine production was in the hands of secular owners.

Small-scale vignerons and poorer peasants were largely shut out of these sales by the high prices the auctions achieved, but some got a start in vineyard ownership by other means. In some parts of southern France (and perhaps elsewhere), peasants took advantage of the fluid legal conditions brought on by the Revolution simply to occupy land and plant it with vines. Some was common land—owned by communities rather than individuals—and some was land that had not been cultivated because it was too hilly or had poor soil but was suitable for vines. Legally or otherwise, the early years of the Revolution saw a dramatic change in the ownership of France’s wine production.

Another Revolutionary law had a long-term effect on the ownership of French vineyards. In 1793, a new inheritance law replaced the patchwork of laws that had existed under the Old Regime. At that time, the property of noble families had gone to the firstborn son, and the rules of inheritance for everyone else varied by region. Some allowed parents discretion to leave their property as they wished, others excluded daughters; yet others favored the firstborn of either sex.

The 1793 law mandated absolute equality of inheritance among all children, with a small proportion at the discretion of the parents to favor (or punish) one or more of their children. Over time, this law led to the fractionalization of land, including vineyards, and it produced the pattern of ownership in many places, notably Burgundy, where individual vineyards are often owned by many proprietors. This law is often attributed to Napoleon, but in fact he adopted the basic egalitarian principle of the Revolutionary law and diluted it by increasing the proportion of property that parents had discretion over.

If the radical redistribution of France’s vineyard land was not an explicit aim of the Revolutionary government, other policies did set out to reconfigure the place of wine in French society and culture. One was to make wine more affordable by eliminating the various taxes that sometimes made it an expensive commodity. Under the Old Regime, sales taxes were imposed on all wine production, and wine was taxed again when it was brought into towns to be sold in bars or by wine merchants. These tariffs (entrées) were levied at town gates and sometimes (as in Paris) at wharves where barrels of wine were unloaded from barges. Tariffs were a flat sum per barrel regardless of the value of the wine, so that ordinary wine was effectively taxed at a much higher rate than more expensive, high-quality wine. Etienne Chevalier, a vigneron who was a member of the first Revolutionary legislature in 1789, complained that “it is deplorable that in a free nation, the poor should pay as much tax for their mediocre wines as the rich pay for their bottles of Burgundy and Champagne.”6 This was widely resented, and smuggling wine into towns was common. Wine barrels were hidden under other goods on carts, or barrels of wine were described as holding less expensive contents, such as vinegar.

These tariffs produced a disparity in the price of wine inside and outside towns. In Paris, a number of drinking places, known as guinguettes, operated just outside the city walls and enabled Parisians to enjoy wine at lower, tariff-free prices than in the city. Vigneron Chevalier declared, “Wine is the basis of survival of the poor citizen of Paris… How many poor families go and eat at the guinguette in winter? There they find honest and inexpensive wine.”7

In the 1780s, just before the Revolution began, the Paris authorities decided to build a new wall that would enclose the guinguettes and subject the wine they sold to city tariffs. Work began on the new wall in 1785, but it was quickly subverted in the interests of keeping wine prices low. Holes were drilled in the walls so that wine could be poured through them and into buckets held on the inside. Eighty such holes were discovered by 1788, and it was said that as soon as one hole was sealed up, another was drilled.

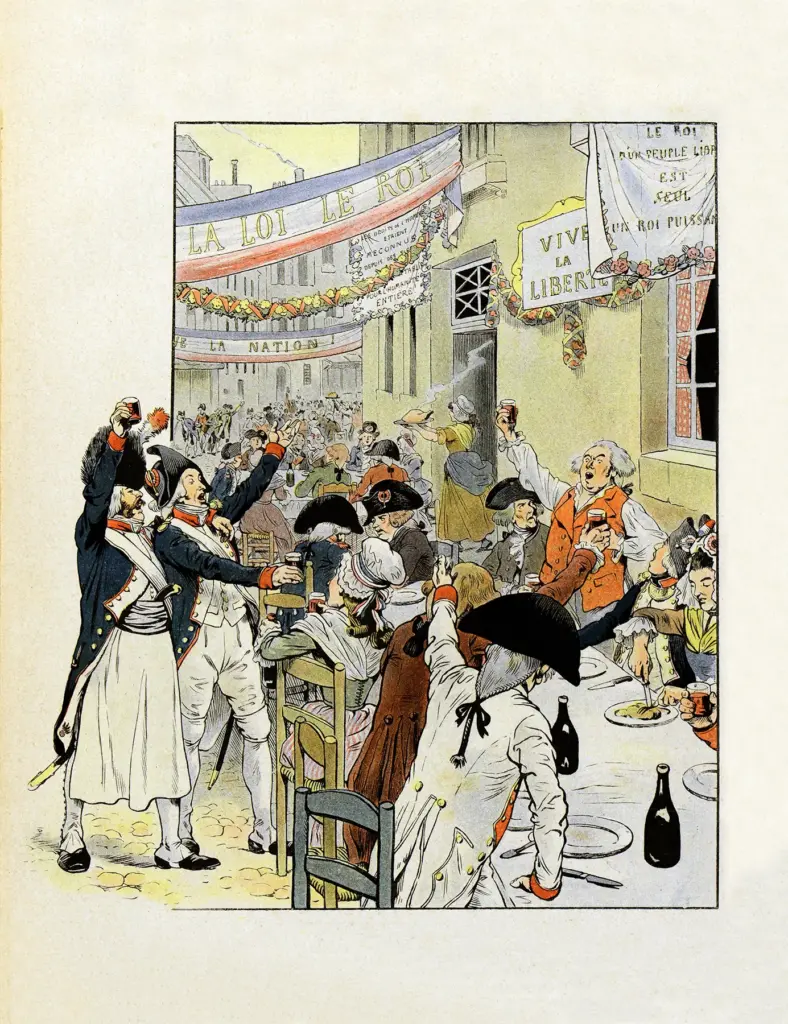

Tariffs were charged not only on wine but on many other goods entering towns, and resentment at their effect on the cost of living led to violence in Paris in July 1789. For four days beginning on July 11—three days before the storming of the Bastille on July 14, the date recognized as the start of the French Revolution—crowds attacked and burned the customs buildings at each of Paris’s gates, where tariffs were levied. This was controlled and targeted violence against tariffs that made life hard for ordinary Parisians. We might say that wine, or anger at the price of wine, was integral to the beginning of the French Revolution.

Wine in the French Revolution: Accessibility, quantity, and quality

When the Revolution got under way and a new government began to govern France in 1789, one of its first instructions was that, until a new tax code was in place, all existing taxes and tariffs should be paid. But in 1791, the government abolished all sales taxes imposed by the state and the entrée tariffs imposed by towns. At midnight on June 1 that year, when the new tax-

free system came into effect, hundreds of carts loaded with now-inexpensive wine rolled unimpeded through the gates and into Paris and other towns throughout France.

It is said that the drinking that night went on until dawn. Hangovers might have lasted for days, but the benefits of inexpensive wine went on for years, until government debt required legislators to reimpose taxes on wine in the late 1790s. Even then, taxes were lower than they had been before the Revolution, and less expensive wine not only permitted higher per capita consumption but also allowed for a broader base of wine consumers. Poorer workers, who might have drunk more water than wine when wine was heavily taxed, could drink wine regularly. The tax reforms of the Revolution, then, helped establish the pattern of high per capita consumption that characterized France in the 19th and much of the 20th century, even though more taxes were imposed during the 1800s.

Throughout the Revolution, the price of wine was a constant preoccupation. Although taxes were removed in 1791, the price of wine—like the price of nearly all commodities—rose steadily, and between 1791 and 1793 it almost doubled. To protect consumers from inflation, price controls (the law of the general maximum) were imposed in late 1793 on basic necessities, such as wine, bread, candles, and firewood. When price controls ended after about a year, the authorities continued to monitor prices. Beaune’s municipal council, for example, fielded numerous complaints “against the sale of wine at exorbitant prices.”8

Revolutionary governments might have intended lower prices to benefit the poor and expand the wine-drinking population of France, but it is not clear that they wanted to increase consumption among existing wine drinkers. In some districts of Burgundy, the opening hours of taverns were reduced so as to deter drunkenness, and the Jacobin Club, Robespierre’s influential base during the first half of the Revolution, disapproved of heavy drinking; members who failed to perform their domestic and civic duties because of drinking could be expelled.

But the authorities did aim to make wine drinking more attractive by combating wine fraud and encouraging sound winemaking, thereby improving the quality of wine. Wine fraud seems not to have been uncommon during the Old Regime, and there are many examples of wine merchants convicted of selling wine diluted with water or adulterated by all manner of additives. In a 1751 case, for example, a Paris wine merchant was found to have blended various wines, water, pear cider, and brandy. Detected by the tasters employed by the wine merchants’ guild, his concoctions were poured into the street, his barrels were burned, his bottles were smashed, his shop was boarded up, and he was banned for life from working as a wine merchant.9

The Revolutionaries, too, cracked down on bad wine, often for reasons of health. The case of François Bertrand at the beginning of this article reflected the long-standing view that good wine was a healthy beverage and that bad wine was harmful. As far back as 1395, Duke Philip the Bold of Burgundy banned the Gamay grape from parts of Burgundy because, he said, “wine of Gamay is of such a nature that it is very harmful to humans, such that a number of people who have used it in the past have been affected by serious illnesses, we have heard.”10

For the most part, however, the Revolutionary authorities were concerned about the way wine tasted, and their aim was to ensure that French people had regular access to wines that were not just affordable and safe to drink, but reliably good quality. Not only was the primary stress on quality new, but so was the role of the state in overseeing wine in this way. Under the Old Regime, guilds had managed questions of quality, adulteration, and outright fraud. But guilds were abolished in 1791, leaving matters of wine integrity to the state to look after.

Wine quality was often defined negatively, in that good-quality wines were neither the fine wines nor the mediocre wines of Old Regime, but a mid-range. It meant not only ridding the market of bad wine but also discouraging the production of fine, expensive wines. In 1794, during the Terror, local authorities were instructed to draw up inventories of the wine cellars owned by individuals identified as enemies of the Republic, such as émigrés and those convicted of political crimes. “Liqueurs, foreign wines, and fine wines of all kinds that the desire for luxury of their former owners had brought together” were to be cataloged so that they might be “used advantageously in exchange for basic necessities.”11

The fate of these wines was unclear, and it is uncertain what, if anything, happened to them. If they were to be sold, who would dare buy them and show themselves to have the aristocratic tastes that were now considered unpatriotic? In one case, we know what became of some of these wines—

the wine cellar of an imprisoned Beaune priest that was placed under seal. It turned out that a member of the town’s Watch Committee (Comité de Surveillance) was seen “very often” helping himself to “good bottles of wine.” When the municipal council investigated, the priest’s housekeeper told them, “My master will be very angry when he returns and finds his wine drunk because it involves a barrel of good, mature wine that he asked me to keep for him. But what can I do, when it is a member of the Watch Committee, and they have the key…?”12 The results of the council’s investigation are not recorded.

Seizing barrels and bottles of fine wines in the cellars of the enemies and suspected enemies of the Revolution was good politics but quite marginal to broader policy related to wine; far more important was ensuring consistency in the quality and safety of the wine generally available to the mass of ordinary citizens. This was an important shift, because there had been little interest in regulating quality under the Old Regime, other than punishing those who committed wine fraud. For the most part, the bulk of the wine on sale was what it was, year by year: good in good years, robust in warm years, green and weak in cool years, and of very variable quality every year.

A sense of the importance of quality comes from Beaune in 1793, when the municipal council decided there should be a wine market early in November each year. They nominated commissioners to taste the wines that producers wanted to exhibit and sell, and they warned that “individuals who bring wines with bad flavors or weak wines will be condemned.”13 Condemned to what wasn’t specified, but the warning probably kept faulty wines away. At the time the Beaune wine market was announced, François Bertrand was languishing in a Paris prison, having been arrested in Seurre, only 18 miles (30km) from Beaune, for serving spoiled wine to soldiers. That alone might have been a salutary example of the fate that could befall a purveyor of bad wine. His subsequent execution, which was publicized on posters widely displayed in the region in November 1794—just as Beaune’s second annual wine market was taking place—would have been a strong deterrent to anyone thinking of trying to sell bad wine.

Good-quality wine thus became the order of the day, and during the Revolution, prizes were offered to vignerons who excelled in their work. In the Burgundy commune of Savigny-lès-Beaune, awards were given for such achievements as “having vines perfectly cultivated, with no diseased plants and with an abundant crop,” for being “an excellent grower, hard-working, and choosing his vines well,” and being “a good grower and a good son, taking care of his very old father who was one of the best vignerons in Savigny.”14

Individuals became engaged in the drive to improve wine quality. In 1790, a Citizen Maupin of Paris wrote to the Burgundy authorities that although their fine wines “are rightly regarded as the best wines in the universe,” Burgundy produced more ordinary wine than fine wine and that the fine wine was inconsistent in quality. He wanted to propose methods of increasing grape yields by one fifth or one quarter, and to improve maturity: “By correcting greenness, one would make them stronger, healthier, and more pleasant, increase their value, and prolong their life.”15

In 1794, one André Gentil, a former member of the Academy of Sciences of Dijon, wrote a memoire that advocated giving up “the merely mechanical way of making wine” in favor of making wine “according to science, based on the combined principles of chemistry and physics and my experiments and observations.” His wines were made from “common grapes” (probably Gamay) and were, he claimed, “similar to the best wines of Burgundy, Champagne, and Bordeaux.”16

Nor should we forget the work of Jean-Antoine Chaptal in promoting the addition of sugar to grape juice in order to compensate for poor ripening and to raise the potential alcohol level—and thus memorialized in the word “chaptalization.” The method was used long before Chaptal’s book advocating it was published in 1801, soon after Napoleon’s coup d’état had ended the Revolution. But Chaptal’s experiments were carried out near Montpellier during the Revolution itself, in the political conditions that promoted the production of good-quality wine. The dissemination of Chaptal’s findings by Napoleon’s government led to the widespread adoption of the method.

Pinot Noir, health, and wealth

Yet despite all these changes in respect of wine during the French Revolution, there were also continuities from the Old Regime. In Burgundy, distinctions continued to be made between Gamay and Pinot Noir, even if they were a bit awkward because they echoed the invidious hierarchy of the Old Regime. But no one could deny that wines made from Pinot Noir fetched higher prices than those made from Gamay. A case before a justice of the peace in the village of Meursault in 1793 centered on the price that one Françoise Blondeau had paid for wine that year and the year before. She asked the court to appoint assessors to taste the wines and judge their quality, because the barrel of wine she had bought in 1792 was a 50/50 blend of Gamay and Pinot Noir, while the one she bought in 1793, and paid much more for, was sold as 100 percent Pinot Noir. She wasn’t convinced of its purity and wanted an expert opinion.17

There was no suggestion in this case that either wine was harmful—this was a matter of potential commercial deception—but the effects of wine on health continued to be a preoccupation of those who regulated wine quality. The municipal council of Beaune complained that some merchants in the town were selling new wine before it was filtered and clarified. “Considering that the distribution of this beverage in this state is infinitely harmful to the health,” the sale of wine before November 1 (about four or five weeks after the harvest at that time) was forbidden.18 (As a point of reference, Beaujolais Nouveau has long been released on the third Thursday in November.)

Citizen Gentil, who proposed a new way of making wine, promoted his wines as not only good quality but healthy: “They will be sought after by the inhabitants of the north, where they work effectively on the nerves, strengthen the stomach, help digestion, revive the spirits, and increase the flow of blood in regions that are very cold and damp.” He foresaw a good market in Russia, “where they drink our wines as we drink water, and our eau-de-vie as we drink wine.” Because it would travel well by land or water, his wine would be sought after in the Midi and America because people will be assured that it reaches them with all its character intact.19

Health also came into play when prestigious vineyards belonging to the Church were sold from 1790 onward. There were ideological problems in asking the high prices that these properties deserved; their value lay not simply in their size and number of vines but in the fact that they produced wines considered very fine and that had therefore commanded high prices during the Old Regime. They were wines that only the wealthy could afford, but how could the Revolutionary authorities convey that—and realize the value of the property—without referring to the wines in terms that were no longer acceptable?

A case in point was the 1793 prospectus for the La Romanée vineyard. It was described as “having the most advantageous [location] for the perfect ripening of the grapes; higher to the west than the east, it receives the first rays of the sun in all seasons, being thus imbued with the strength of the greatest heat of the day.” As for the wine, it was “the most excellent of all those of the Côte d’Or and even of all the vineyards of the French Republic.” It had a “brilliant and velvety color, its ardor and its aroma charm all the senses.” If well kept, it was at its best in its eighth or tenth year. Did this mean it was a delicious wine that appealed to the refined palates of the wealthy? No, it was a healthy—indeed a life-prolonging—wine: “It is then a balm for the elderly, the weak, and the disabled, and it will restore life to the dying.”20

Wines from that vineyard might not have found their way to the glasses and goblets of the masses, but the fundamental aim of the Revolutionary authorities in Burgundy was to provide an adequate supply of decent-quality, healthy wine at an affordable price. In December 1793, all the Gamay wine available in and around Beaune was requisitioned to supply the city.21 Gamay, which was widely planted in Burgundy, despite Duke Philip’s 1395 ordinance, was considered vin commun, a good wine even though inferior to the vin fin made from Pinot Noir. Gamay vines were far higher-yielding than Pinot Noir, making Gamay less expensive, and more barrels of Gamay wine were requisitioned for the city and for billeted soldiers in 1794 and 1795 and later in the decade.22

Wine was clearly a staple of military rations and of diet more generally, such that people expected to be able to drink it regularly. Beer was very much an outsider in wine-producing regions such as Burgundy; in 1798, when the Beaune municipal council calculated its anticipated tax revenues from alcoholic beverages, it based them on the consumption of 14,000 275-liter barrels of wine and 200 138-liter barrels of beer.23 The next year, the wine estimate was up by a thousand barrels, to 15,000. Consumption at this level meant that each of Beaune’s 10,000 inhabitants—women, men, and children—had access to 413 liters of wine a year, more than a liter a day. Subtract the likely 40 percent of the population that was under 19 years of age, and each adult had access to almost 2 liters of wine a day.

From bien national to vin national

As if to emphasize the importance of wine in Burgundy, people rejected alternatives. In 1793, the Minister of War let anyone in Burgundy providing accommodation for volunteer soldiers to supply them with cider or beer rather than wine because the 1792 harvest had been small and wine prices were high. But he was forced to reverse the decision when he was told that substituting cider or beer for wine would “result in disturbances on the part of National Volunteers who wanted their hosts to provide them only with wine.”24

Wine might have been a staple, but it was a distant second to grain. There are plenty of examples of grain and bread riots in 18th-century France, but wine riots seem to have been few and far between, if they occurred at all. One was threatened at Martigues, the now-picturesque village near Marseille, in 1793. The local Popular Society warned that if the wine supply ran out before the next harvest, there could be “a general uprising” by fishermen, who relied on it while at sea.25

If the aim of Revolutionary governments was to achieve a standard of good-quality wine by ridding markets of fine wines and poor wines, there was no pretense that all wines were the same quality and no effort to make all vignerons sell all their wine at a standard price. As difficult as it might have been to acknowledge during the more radical phases of the Revolution, inequalities of wealth persisted, and there were people willing to pay more for wines from prestigious districts or regions—the sort of people who paid high prices for expropriated vineyards. The price controls implemented in 1793 made clear distinctions among the wine-producing villages of Burgundy: top-quality red wines from Volnay and Pommard were priced at 560 to 570 livres per queue (a barrel of 456 liters), while wines from Savigny were capped at 340 livres, and those from Monthelie at 250 livres. All those wines were made from Pinot Noir. Wines that were a blend of Pinot Noir and Gamay were priced at a maximum of 200 livres a queue, while wines made from Gamay alone were capped at 180 livres.26

At the level of political culture, however, there seems to have been an attempt to portray wine as a beverage that overrode distinctions of wealth and occupation and that united French citizens. We are 100 years before the time that wine was officially designated the national beverage of France, but that was the import of Revolutionary policy. Wine flowed freely at the various festivals sponsored by the Revolutionary state—the events that replaced the host of religious festivals, feast days, and saints’ days of the Old Regime that were occasions of deep drinking as much as (if not more than) profound piety.

Quite possibly, providing a reliable supply of good-quality wine at affordable prices helped rally many poorer French citizens to the Revolution. They were not the first and would not be the last people to measure the success of their government by what was on their plates—or, in this case, what was in their glasses. It was all well and good for Revolutionary leaders to talk about liberty and equality, but removing taxes on wine and ensuring that it was good quality gave these ideals tangible form. By expanding the wine market and improving wine quality, the Revolutionary period might well have embedded wine drinking more firmly into French culture as an expectation that was embraced by successive generations, no matter what their political preferences.

In this sense, the French Revolution established some of the bases of the French wine industry and the place of wine in French culture for more than 100 years. Some changes, such as the removal of the Church from wine production, were permanent. Others were transient; taxes were abolished in 1791 but reimposed toward the end of the Revolution and more were added in the 1800s. As for wine quality, it would be nice to think that any improvements during the Revolution persisted, but it is unlikely that they did. Indeed, the 19th century—even without the adulterated wines of the phylloxera period—seems to have been a heyday for wine fraud in France. Still, the model of quality was there, and the Revolution established the role of the state in controlling wine quality.

In respect of wine, then, the legacy of the French Revolution is mixed, but there is no doubt that it was an important moment in the history of French wine, as it was in the history of France more generally. François Bertrand would not have appreciated it, but his execution—as appalling as it was—for serving bad wine, makes some sense within the context of the Revolution. Everything—wine included—was highly political in a time of revolutionary upheaval.

Notes

1. Archives Départementales de la Côte d’Or (hereafter ADCO), L 1027, Jugement du Tribunal Criminel Révolutionnaire (26 Floréal An II/15 May 1794).

2. Rod Phillips, French Wine: A History (University of California Press, Sacramento; 2016), pp.118–19.

3. ADCO, G 4169, Volnay.

4 ADCO, 1Q 74, Biens nationaux, 1790–92.

5. ADCO, 1Q 80, Biens nationaux, 1790–92.

6. Marcel Lachiver, Vins, Vignes, et Vignerons: Histoire du Vignoble Français (Fayard, Paris; 1988), pp.352–53.

7. Ibid.

8. Archives Municipales de Beaune (hereafter AM Beaune), Registre de Délibérations du Conseil Municipal de Beaune, 1D-3, 4 Brumaire An III/ October 25, 1794.

9. Jugement de M le Lieutenant Général de Police… du 24 Mars 1751 (G Lamesle, Paris; 1751).

10. See Rod Phillips, “By Decree: The Duke of Burgundy’s 14th-Century AOC,” The World of Fine Wine 71 (2021), pp.120–29.

11. ADCO, L 544, Subsistances. 19 Germinal An II/April 8, 1794.

12. AM Beaune, 1D-3 Registre de Délibérations du Conseil Municipal de Beaune, 44v, 13 Fructidor An II

13. AM Beaune, 1D-2, 71v (22 Vendémiaire An II/October 13, 1793).

14. ADCO, L 465, Fête d’agriculture.

15. ADCO, L 574, Agriculture, August 14, 1790.

16. Archives Municipales de Dijon (hereafter AM Dijon), 3F/27 (12 Brumaire An III/November 2, 1794).

17. ADCO, L 3735, Juge de Paix, Meursault, June 14, 1793.

18. AM Beaune, 1D-6 25, Fructidor An VI/September 11, 1798.

19. AM Dijon, 3F/27, 12 Brumaire An III/November 2, 1794.

20. Richard Olney, Romanée-Conti: The World’s Most Fabled Wine (Rizzoli, New York; 1995), p.31.

21. AM Beaune, 1D-2, 1 Nivôse An II/December 21, 1793.

22. AM Beaune, 1D-3, 23 Fructidor An III/September 9, 1794.

23. AM Beaune, 1D-7, 14 Fructidor An VII/August 31, 1799.

24. ADCO, L 1027, September 26, 1792.

25. Archives Départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône (Marseille), L 376, Subsistances 1792-An VIII. Letter from officiers municipaux, January 11, 1793.

26. ADCO, L 1401, Maximum.