It may not conform to conventional definitions of a cellar, but Tim James finds delight and surprise in his dispersed, somewhat haphazard wine collection.

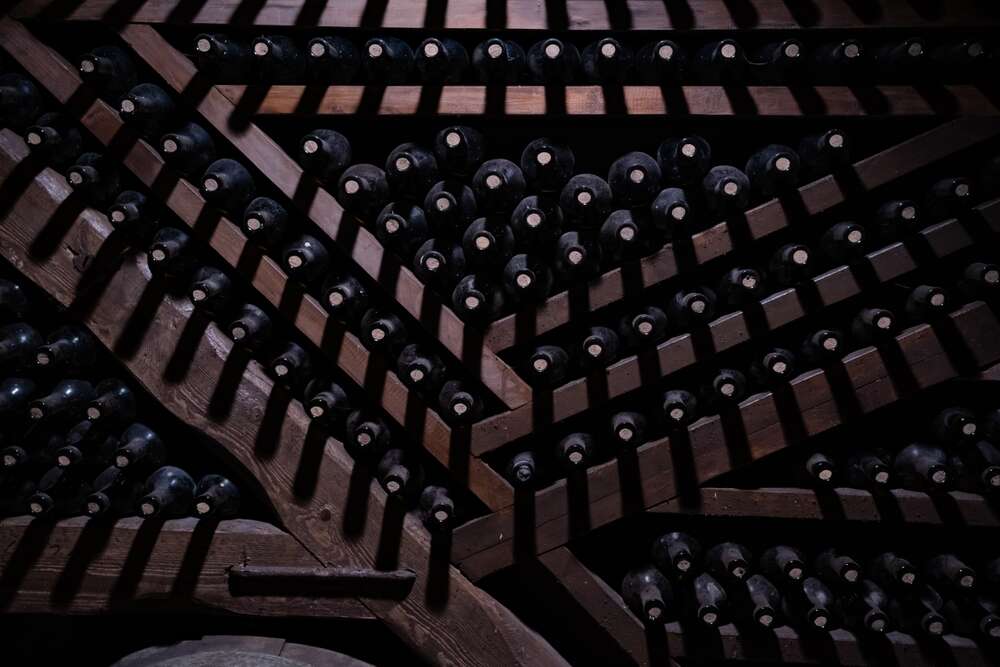

There’s something to be said for a degree of chaos in a private wine cellar. In case the idea of “cellar” conjures up a more or less grand image of racks or bins receding into the cool, dark distance, I should hastily say that I’m talking about my own, which is only a cellar by linguistic courtesy, using the word as a sort of collective noun for an accumulation of bottles.

My cellar doesn’t even have a physical coherence; some wines are in air-conditioned commercial space here in Cape Town (irritatingly expensive but with unchaotic, even superbly organized records); a few cases are with a friend who has something more like an actual cellar (though modest and above-ground); some that are for drinking within four or five years of the vintage are in a cupboard with a fairly stable temperature.

The majority, though, are in four wine fridges—three larger ones in my garage and a smaller one, for stuff I plan to drink fairly soon, at home. The organizational problem inherent in wine fridges, especially those with shallow drawers, is that, however logical your disposition of the wines starts off being, once you have gaps that need to be filled, some chaos is bound to start developing. I aim to have a complete reboot every few years, but the neatness is short-lived, and randomness accrues.

Le vin perdu

There are perhaps 800 or 900 bottles in total in my shifting accumulation. (I’ve never done more than a rough count, and there’s certainly nothing as useful as an up-to-date cellar-book.) Rather more than half the bottles are of local, South African wine, the rest largely from France and Germany, not enough Italian, with some Sherry and a bit of Port and, for all I know, a bottle or two from elsewhere. Which brings me back to my suggestion of there being a possible advantage in a lack of organization: There’s always the chance of a nice surprise.

Unfortunately, a nasty surprise is just as possible, especially when as leaky a memory as mine is involved. In the context of a discussion about the ageability of modern Cape wines, I recently wrote sentimentally about special bottles that I would never want to broach, however ready they were. One I mentioned was the first vintage (the 2012) of Alheit’s Radio Lazarus—from a previously badly neglected 1971 Stellenbosch vineyard of Chenin, giving minuscule yields. I had visited the hilltop vineyard with Chris Alheit soon after and had come to feel the sense of investment that such visits can give, with a concomitant increase in the wonderfulness of a wine. (And this was a truly fine wine anyway.) But in the recent years of drought, the old bush vines—and those of the other nearby vineyard that had supplemented it in latter years—finally succumbed (desperately hungry and thirsty buck didn’t help), despite the most tender, even anguished care; Lazarus died once more.

After writing glibly about the importance of my last bottle of 2012, I thought I should just go and check. I did, in this case, know exactly where it would be. Where it once was, that is: My sentimentality had given way to sensual indulgence at some point. Never mind, I’ve transferred the sentiment to the final, tiny bottling of Radio Lazarus, the 2017 (this one fermented and matured only in clay pots). And I know I have a whole six-bottle case of that, happily safe from my marauding fingers in my friend’s cellar—a place I rarely visit, and one that usually manages to render up some pleasant surprise in a bottle I’d forgotten about but that’s ready for drinking. I’m pretty sure there are still a few lovely old-fashioned Mosel Spätlese 2005 Rieslings that should be gorgeously on the edge of decadence now.

Special ones in the cellar

The chaos and the surprises are both made more likely, in fact, by many of my wine purchases being in quantities of less than a case, and there are quite a few single bottles. And even cases diminish to a single vanishing point at some stage. I have only a few local wines left from the last century, at least partly because there were not many worth keeping—from the 1980s onward, anyway. I do have a bottle of 1966 GS Cabernet, a great wine unhurriedly awaiting a special occasion.

There’s no sentiment attached to the GS—it came as part of a cold-blooded swap for an etching. But there’s a lot in my one remaining bottle of what, looking back, one can see as the first great wine of the rediscovered Swartland, and therefore of the central focus of my wine life for a few decades; and arguably of the South African wine revolution: Eben Sadie’s maiden Columella, 2000. I am confident I know where that bottle is—in the tatty old wine fridge whose temperature is stuck at 54°F (12°C), and I don’t go colder than that.

That temperature’s not quite what it would be in the dungeon of an old Scottish castle, but my wines are, anyway, not quite up to the standard of a stash of pre-phylloxera Bordeaux. It should keep the wine (which was drinking well when I had another bottle a few years back) stable enough until a plausible occasion arrives—or doesn’t.