I’d wager that anyone who reads seriously — a pitiable sort of word to use for this visceral pleasure — has benchmark books, books we read again and again at different points in our lives. We measure our own shapes and learn our own narratives by seeing how the new “us” responds to the text we’ve read before. Some books, it turns out, really weren’t all that good, and others are good in new and revealing ways, and sometimes we’ve long since learned the tricks that dazzled our eager young eyes. What ravished us then is rueful to us now. And of course, what sailed right by our callow young minds becomes crucial to us in midlife.

It isn’t only the grave or the solemn whose voices we learn to hear. My own crush on Muscat is a direct result of my getting older and learning to cherish the baby’s coos and gurgles. Muscat is primordial innocence in liquid form, and when I look at my rapidly graying beard in the mirror, I think of the splash of eternal youth I’ll drink in a few hours. But none of this is especially original; we all know our tastes change as we move through life. Yet the word “taste” seems too narrow, because what changes is not only what we taste but who we are, tasting. The part of us that used to be entertained by massive powerful wines was also at home in cacophonous restaurants, and now we’re grateful for a little quiet. Simple force is a thing that palls. And this is common, maybe even blatant; we learn to cherish more subtle things.

There’s something below this phenomenon that I want to explore. Because when I read my old tasting notes — which I do when I’m home alone with the blinds drawn — I see the work of a young man, effulgent with his own delight, certain the world is lyrically arranged just for his very pleasure. At least he is grateful and willing to engage. And his — my — influences were a bygone generation of wine writers who had no fear of writing extravagantly, and who encouraged me to suppose wine could be extravagantly beautiful. So, I was ready — at times too ready. But if this was the least of my youthful errors (as alas it wasn’t), I could easily indulge it. There are worse things than to see wine as a bringer of beauty.

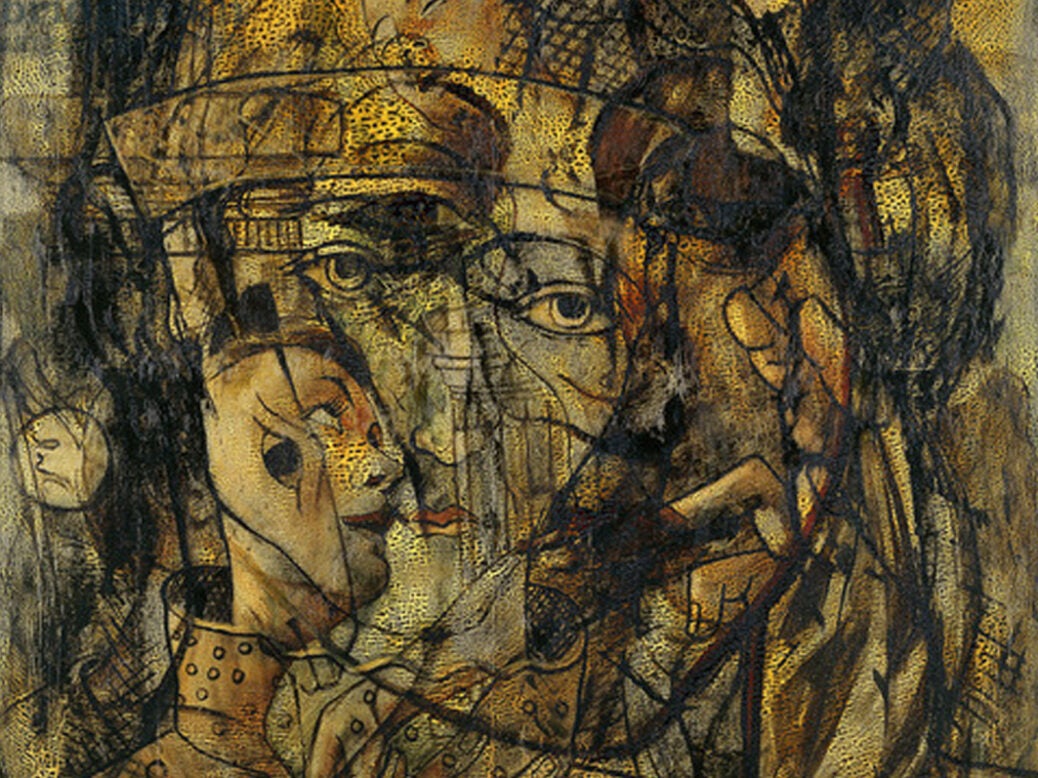

One starts there. Beauty comes to us in many forms, and one of them is wine. And then one continues, I think, and the first question is What is the “us” to whom wine comes?, because my life has been not only a succession of selves forming and fading over time but an entire and often unruly assembly of selves, clamoring at once for my attention. These many selves also shape-shift and come into being and leave again, sometimes returning and other times not, and sometimes returning in a different form. Lately I’ve found an especially needy homesick self whose clamor was drowned out by my excitement in traveling as a younger man. Not any more. The part of me that still loves going away is like a very drowsy dog who needs to be cajoled into wakefulness.

I think perhaps that part of the soul’s business is gradually to pare down this parliament of selves we carry through life, until some true voice can be heard. It sounds a little affected to say “the soul’s voice,” but I can’t contrive a better phrase. The young soul tries on a bunch of different voices, a whole chorus trilling away. Then fewer and fewer, because the soul knows before we ourselves do, that time is drawing down, and if we’re ever going to hear the pure authentic voice, we’d better listen now. I’ve said that if we live long enough, we walk with a lot of ghosts, but the unnerving surprise is that eventually we walk with our own. Maybe it arrives when it’s summoned, and maybe it was somewhere in the back of the scrum, but however it happens, part of me is walking with the Terry who won’t be here forever.

Wine a herald of time

What can this possibly have to do with wine? Here is an experience I recently had, tasting a wine of my birth year during a visit to Gaston Chiquet in Champagne.

It was a quiet Sunday, and we’d just driven from Germany. My hotel’s Wi-Fi was balky, and it was a crisis time at the company, so I was distracted and jangly. But at least we’d be with Nicolas Chiquet, who is among my favorite people, and I knew I’d get lost in the wines. That’s easy to do there.

Nicolas says he doesn’t have very many people who love old wines, so when we visit it’s an opportunity to plunder the cellar. That makes me feel bashful. I mean, who am I to deserve this? And the cellar, after all, is finite; when those bottles are gone, they’re gone.

Two wormy old bottles arrived, coated in cellar fuzz. Your hands get all goopy if you hold a bottle like that. The cork was balky in the first one, and in the moments after it was poured, none of us could be sure it wasn’t corked. Old wine sometimes starts off smelling like the cellar — moldy. The wine was “from the ’50s,” but more than that we could not know. Nicolas thought it may have been demi-sec, which would have made it Non-Vintage quality, which implies Meunier. Yes, maybe. The color was oddly fresh — further evidence of TCA — and the initial aromas were riotous until the TCA subsumed them; truffle, brown butter, tonka bean, orange zest, maple, melon, some crazy esterization of fructose, and we had a good 5-10 minutes with it before we all had to agree, sadly, that the cork taste was winning the race. Still, I was grateful to visit the wine at all.

Nicolas knew what the next wine was, but I don’t know if he knew it was my birth year, 1953. It was one of his last four bottles. I was half in tears before the bottle was open — me and my little 60th birthday last summer. As he eased the cork from the neck of the bottle, I felt suitably grave. Mortality, beauty, friendship; the little parlor where we tasted might as well have been a chapel.

It was a difficult time, and I was a long way from myself. The man I brought to that glass was in a state of what, me, now? Nicolas said the cork was strong, “perfect,” and the wine was poured with delicate ceremony. I sniffed it, and it took all my strength not to weep out loud. Not that I’m scared about crying in front of others, but this wine threatened to undo me. Still, my eyes filled and my voice caught, and I followed the wine into whatever silence and starlight it wanted to show me.

It smelled like every weeping buttered nut since the beginning of time. It had a four-octave complexity, a full measure of power that was virtually heroic, and the vitality of a great wine from a great vintage, in miraculous condition. I was out past the galaxy of associations; there was only an infinitely tender and mysteriously complex loveliness, a consoling sweetness in the finish that froze my heart with ecstasy and regret, as such things always do — that sweet sad message of the beauty of the world, telling me, Try to not forget this. It’s hard, I know, but try.

The room grew very quiet, four tasters, stilled, our souls coated in silk, expanding infinitely. There were murmurings in the wine, and the silence was a balm. But what I heard was unquiet. I haven’t given much credence to “turning 60” because I don’t know what it means. I don’t feel “60,” whatever that is, and I feel no dilution of passion. I do feel certain changes in the body, asking me to be a little more gentle, and I feel powerful shifts among my sources of joy, all of them asking me to spend more time at my wellsprings, the taproots and fountainheads that a young man feels he can safely ignore. I know I can’t ignore them now. There’s not enough time. And this dancing thing in my glass was a herald of time.

How much time do I have left, I wondered. Believe me, I’m not especially lugubrious, and I’m not fixated on questions of death. But 60, you know; you let a few of those thoughts in. You can’t help it. Sitting there, drinking a wine precisely as old as I was, aware of the dark penumbra always around beauty, I asked myself if I felt “ready” for death. I mean in an abstract way. Ask me, “Are you ready to die?” and I’ll say, “Fuck no!” But ask, “Are you ready for death?” and I’ll say, “For sure. Not tomorrow, but I guess eventually.” But this wine wouldn’t let me split that question. It knew very well how I really felt: How can I bear to leave this world? This world.

And what of all the days and days between these moments of still-framed stunning kindness? The days when we forget what it actually is we do by living. In the rapturous gravity of these exquisite flavors, I think I never want another single one of those days. But of course I do. I want those ordinary beats of living, and I want them never to stop. But I also don’t want to forget the way a wine like this can light up the interior, and we need to wander down there now and again and do a census of all the strange critters who live there. They get obstreperous otherwise. I took another lost sip of wine. I must have been quiet for a long time. “Wow, that’s some tasting note,” somebody said as I wrote and wrote.

I can’t fathom what I’d have made of a wine like that if I drank it in my 30s. I know my affect and my language would have been more rapturous, and that’s fine; rapture is a form of gratitude. But I think the soul of that young man was by no means as lavish as his prose. It was quietly patient. At least I was responding. At least there was a spark, and nothing to block ignition. Maybe it’s as simple as this: An older man drinks, and his ghost drinks with him. Then the question is, Who’s writing the tasting note?

A wine bigger than I

During this spring, there was a sequence of small damaging things. One had to do with the business, and the other with my normally (or abnormally) ruddy health. I’ve always been the guy who “doesn’t get sick” or who gets the weensiest version of whatever illness I do get. But these days I’ve been just sick enough to feel, for perhaps the first time, vulnerable. I can no longer assume I will always prevail. When my sense of smell came back, I was transfixed by the aroma of nutmeg — I sniffed the jar of nutmeg to measure how much sense of smell I’d lost — as though it were a shaman of the world’s ridiculous vitality. I rummaged through the kitchen like a crazy person, sniffing everything in reach, the culinary lavender, the dried rose petals, the saffron and the peppercorns and the pumpkin seed oil, feeling almost militantly delighted. See? I told you I’d get better.

Being weak wasn’t entirely a bad thing for me. I had to write my Austrian offering, and I was curious to see if it would reek of a sick dude’s prose. But no, it was the usual slurry. Except that in one or two places, I felt the arrival of something new something I’d never thought of, or hadn’t had the words to say.

It was stark. And being stark, it could seem almost brutal. I couldn’t find the sugar coating. Things just insisted; experience decided not to spare my feelings. This was true although I was writing about pleasurable things. But I seemed to be receiving pleasure in a different way. Tasting at Nigl, I had every reason to feel ecstatic; Martin Nigl had the precise vintage he was meant to have, and the wines accumulated into a giddy parade of the microsurgical clarity his wines show at their best. In fact I was excited; we’d waited a while for a vintage like this. But when I arrived at the sine qua non, the best Riesling, my thoughts veered away into an odd new vector. I wrote: “Sometimes I think the portal to greatness is a kind of void. First they take away gravity, then they take your words, and when they’ve made you feel entirely helpless, then they let you in. Each time I drink a great wine, I have the feeling ‘None of my tricks are any good here.’ All the little stuff we deploy to try to stay on top of life. In some sense, we come to greatness naked, not because greatness ‘demands’ it, but because that is its language.”

None of the things we agree are exalted is easy. Love will kill us. Ecstasy flattens us afterward. Greatness strips us down before it lets us in. These things are gorgeous and fierce, and sometimes we seek comfort in that which is pretty and reassuring and where we maintain the fantasy of control. With a great wine, we begin by trying to write about it the way we do with all other wines; we show what we’ve seen by breaking it down. If we’re delighted or amazed, we try to say why. The wine is an object we try to describe. With a great wine, our words are like tiny fists raining useless blows against a huge edifice of indifference. All we can hope to say is what it’s like to be there. Then if you can, you say what the wine is like, in some new way, and your reader is sure you’re unwell.

There are “easy” great wines. They overwhelm you, but they’re visible — incandescent, but visible. This Riesling isn’t quite that kind of wine. It has the esoteric, exotic aromas I expected to encounter, but the palate is nearly incomprehensible. It alights on each living thing in a kingdom of flowers, stone fruits, and herbs, releasing a massive sensual vinosity within which all the world seems to be steeping. The wine was bigger than I was. I’ll have to buy half bottles!

It felt like a kind of defeat. It was a kind of defeat; it subdued whatever part of me that presumed the wine could be apprehended and then described in language akin to its particular fierce beauty. Clearly, that wasn’t happening. And yet I was granted access to something that felt empty, a sort of purgatory to prepare me to meet the wine in its own purity. The joke was, language wasn’t needed anymore. Everything was understood, and nothing could be said. I never actually felt more merged with a wine, as if we’d mingled our very cells, yet I was rather brusquely stripped of all my “talent.” And if I simply wrote, “This was great wine; some of you know what I mean,” that’s the ghost tapping out his code, wondering whether some other ghost is at the other end of the filament.

Wine and the ghost-self

It continues. I’ve been finding that each new experience of a great wine seems to shove me toward a relentless severity. It isn’t exactly bitter, but it knows if I tell even the tiniest lie. In Reading Between the Wines, I wrote about Michi Moosbrugger’s “Tradition” bottlings, in a chapter about mysticism. Michi sought to enter the mentality of cellar masters 130 years ago — a kind of time travel in itself — and the resulting wines convey an aura so ethereal that I wonder if the modern-wine drinker has any means of grasping them. The wines have continued to be curiously and exquisitely beautiful, but nothing prepared me for what poured from my pen tasting the most recent Gruner Veltliner.

It smells like a sorghum brine, or like a beef consommé and then a giddy popping flourish of saffron; a total thrall of aroma, leading to perhaps the greatest GV I’ve ever had. I’d recently drunk the 2008 and was properly silenced by it, but this wine’s grown more intricate over the years. It’s so creamy, so musical, so grave yet so hopeful. It isn’t “sad”; it’s grave because life is serious. Stocks and gelées, spices and glazes, a kitchen full of stories, a home full of welcome, a respite in the unquiet life.

I’ll try to say what I mean. Not long ago, my wife was ill, and one night I was awake for a time, and I heard her lungs rattle as she breathed in her sleep. I felt first a tidal surge of love: She’s sick, and she’s so little, just one little human with her rattly lungs. And then I wanted to do something, to snuggle her, but I was afraid to wake her, she needed her sleep so much; so I lay there, and my love had nowhere to go. It was just my useless love in the dark. And then, of course, I thought of the last time I’d snapped at her, and all I felt was awful; doesn’t she have enough trouble without contending with bossy old me? Then I thought I’d apologize in the morning, but I knew I wouldn’t. These are starry thoughts you feel while you lay there in love and ashamed and think about your ruined kindness.

This wine doesn’t embody those feelings; it addresses them. It speaks to the you that is hidden away. What other things talk to us like that? And who, finally, is the listener?

It is your ghost-self; it is the “you” you do not own; it is the doomed longing to unite all your clamorous factions into a single unified self, something you can describe and control; it is the rueful laughter at all the human foible; it is the grief of each thing within us that we starve and ignore. And this ghost means well by you, as long as you understand that it is honest and blind. These days, if I encounter a great wine, the first thing I feel is, Uh-oh, here goes, and then I don’t know any more. I used to think I knew, but beauty wants something it can only ask for in ghost language, and now we are both of us drenched in passion, my ghost and me, shining darkly and flying blind.