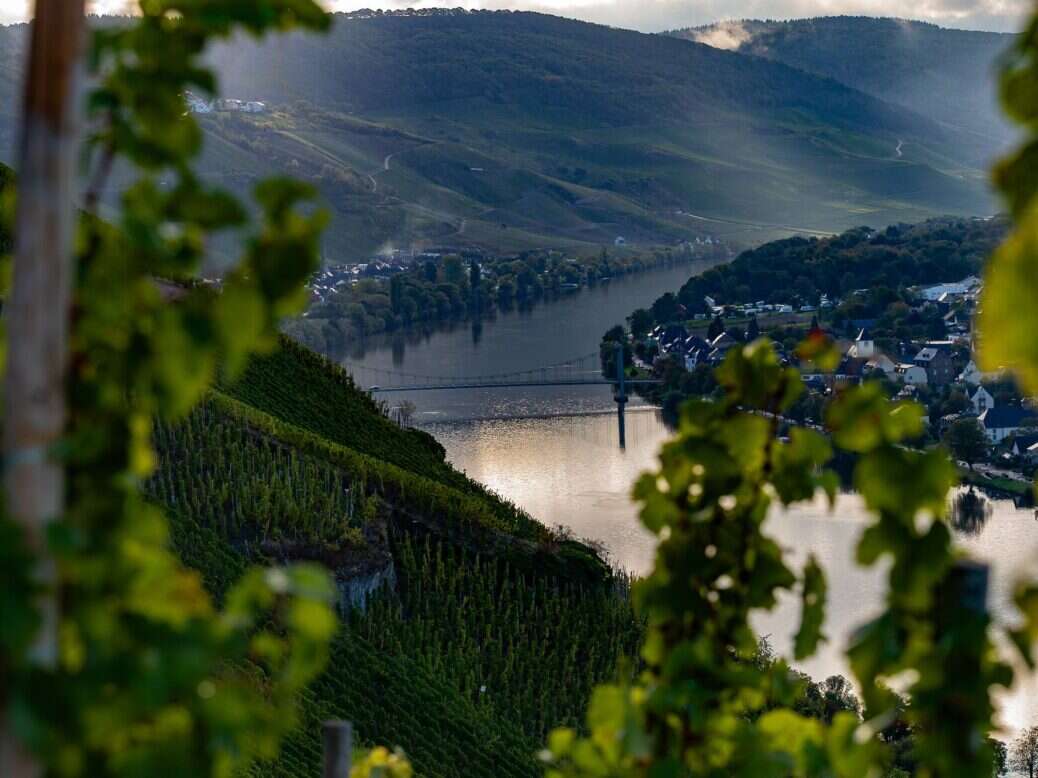

The unshowy, textured, utterly authentic wines of Selbach-Oster are the essence of the Mosel, says Terry Theise as he begins his three-part exploration of the estate’s latest set of releases.

They’ll catch on, eventually, and sometimes. I think the moment of arrival was last summer, when the important German newspaper the Frankfurter Allgemein did something it almost never does, and devoted its wine column to a single producer—Selbach-Oster.

Johannes Selbach himself is a conspicuous sort of gentleman. He travels the world selling and promoting his wines, as his estate is sizeable by Mosel standards, and also Johannes likes to travel. Johannes’ wines, however, are the opposite of conspicuous. Though far from modest or retiring, they avoid all the gestures by which wines seek to attract attention. You and I know all too well what those gestures are, and how tiresome they have become.

I wouldn’t describe Selbach’s wines as “introverted” but I would call them interior, because they focus on texture and their north star is authenticity. I’ve drunk them in detail for nearly 50 years, and never had one I’d describe as “gaudy.” They are to my mind virtuosic, but there’s more than one expression of virtuosity. One way is, you play your instrument, and the instrument plays the music. The other is you move through the instrument like a ghost, and play the music directly.

I’m not sure I’d describe Johannes Selbach as “modest” but I’m very sure I’d describe him as self-effacing as a vintner. If he is any sort of personage in the wine world that’s more a matter of personal exposure and articulacy. But he doesn’t enact a visible imprint on the wines. When I taste them I feel like I’m inhaling an ether of pure undiluted Mosel-ness, and I know they’re Johannes’ wines but the man himself is off to the side.

A beacon of meaning

I’ve written much about this domain. They are a beacon of meaning to me in my wine life, and in my life as a whole. Much of what I’ve learned about honor, integrity, and authenticity, I have learned from this family, and these wines.

Among more prosaic (but no less important) considerations, Johannes Selbach was the first Mosel vintner who was able to solve the “sponti problem,” an issue in which ambient-fermented wines were often hidden behind stinky veils, and stubbornly unapproachable in their youth. This was exactly when I was trying to taste them, and not long after, it was when I was showing them to my customers, and while I knew (and argued) that it wasn’t a “flaw” it was certainly a nuisance. So at one point—it must have been around fifteen years ago—I asked Johannes whether there was any way to preserve the virtues of spontaneous ferments while reducing or eliminating those annoying early odors. He said something like “Let me work on that,” and within a few vintages the problem appeared to have been solved.

Tasting these little baby ‘20s, most of which are spontis, I was reassured and delighted to find all the things I love about that kind of wine. As will you. It’s helpful to lock these wines in as a paradigm of how the style should (and can) be, because believe me, you won’t need to travel far to find young Mosel Rieslings that hold you on the other side of a wall. At times I’m willing to wait (or to swirl the hapless wine for minutes on end), but sometimes it just pisses me off. I’m sure no grower intends to display contempt for his customers, but he is issuing a consumer product that isn’t ready to be consumed, and which is sometimes marred by truly objectionable aromas. When such growers say, as they sometimes do, “You pay this price now for something superior later on,” I want to ask Why should I pay that price?

So kudos to Selbach for solving the problem for us! Even the most militant sponti in this collection—the en-bloc bottling from Rotlay—is entirely beautiful and standing by to give youthful pleasure, if that’s how you wish to drink it.

Selbach-Oster red and rosé wines

2018 Spätburgunder

Limpid garnet, like a ripe-vintage Beaujolais. Fragrance is dusty and pretty from a Spiegelau (the large white-wine stem that’s actually better for light-bodied reds), and more precise and definitely pretty from the Jancis. But the palate is impressively charming from either glass!

It is not, however, merely charming. The wine has some “ideas.”

Johannes tells me: “It is grown partially in Zeltinger Himmelreich not too far behind the church in Rachtig. The other portion comes from Kinheim. Both have soils that are slate with loam and humus mixed in. The vines are a global “potpourri“ of German ( Marienfelder and some Geisenheim ) and Swiss clones.”

“Hand harvest of picture perfect fruit, grapes mostly destemmed, however about 15% were left with stems. The grapes underwent classic open top fermentation with punchdown of the cap. Transfer of the dry wine into mostly 3rd and some 4th year Francois Frères barriques to finish fermentation and undergo malolactic fermentation. Long ageing on the lees. Unfiltered. Obviously no chaptalization.”

The Jancis glass reveals some angles and corners and a spiciness that veers toward black pepper. Oxygen lets loose some tannin from both glasses. In both cases the fruit is morello cherry, with a little background funk from the Jancis and more grilled Portobello (with many shavings of a bold peppercorn, like Penja). It’s quite a shape-shifter, and if I say it’s “charming” you might receive it as firm and peppery—and vice-versa.

It is both ambitious and sensible; that is, it isn’t overly ambitious for its environment. Nor does it strut a lot of extraction and wood; it’s light but not slight. I’m curious to see whether the fruit moves forward or backwards over the next few days.

48 hours later there is discernibly more fruit, ie, oxidation seems to help the wine if fruit is what you’re after. Decanting might be useful. Structural elements remain much as before; if anything the wine’s a bit tougher than it first seemed. Johannes may be trying to respect the tensions of steep land and the lightness of the northerly latitude, while not surrendering to an assumption the wine should be slight and (merely) attractive. Of course if you want to make the Pinot Noir gods laugh, tell them your intentions!

But that’s not the end of the story. I hate discarding wine, and the 1-2 glasses worth left in the bottle sat in the cellar for two weeks, before I pulled it to supplement a dinner bottle we’d finished too quickly—oh yeah, that happens—and all this Selbach needed was to be drinkable. Right! Shall I tell you what happened or do you already know?

2017 Spätburgunder Trocken— glug-glug-glug?

Johannes must have been pleased with my report on the above (which I shared with him per his request for a quick comment), because he’s sent the ’17 now, which, if I tasted it before, I don’t remember. It’s unfiltered and shows it; it also has a riper fragrance with a fuller middle. It’s fleshier than the ’18, but by no means corpulent. It smells good, a true Old-World PN aroma.

I must say, this wine is excellent, and right out of the gate. You’ll have seen my tasting saga with the ’18, but this hits the ground running. It has truly lovely fruit! It’s sensationally limpid and charming. It’s almost too polished for my “glug-glug” thing, but it’s also addictively tasty, which counts for a lot in my world. Are we ready to cherish the virtues of “little” wines when they’re this delightful?

There’s material to “consider” in the fruit, if you want to, but I don’t discern anything I’d call Mosel-ness, unless it’s a lucidity often imparted by steep slopes, or steep-ish in this instance. Nah, it’s just a chipper sort of wine that comes to you tail-wagging and ready for a game. If we are too sophisticated to appreciate such wines, then shame on us, because we’re wasting our relationships to wine.

2020 Spätburgunder Rosé Trocken

Not that Johannes would ever pander, but <sigh> … it had to happen, right? What Christian Dautel calls “the dreaded rosé.” On the other hand, the option to make a rosé gives strength to the Spätburgunder, and people like rosé, and there are some good ones along the Mosel (Adam!), and why not? Plus I have to say—and I mean this as a compliment—this rosé isn’t especially well behaved. This could be because it was bottled quite early, before the end of that year, and sometimes such wines have a sort of frozen adolescence.

It’s light but not innocuous. Finishes with a lot of grip. Shows a chewy structure under a surprisingly restrained fruitiness. Has a side-swipe of funk, the way Heidi Schröck’s rosé also has, though here the fruit is more orthodox. From the middle to the back palate you can even refer to minerality. Any more firm and I’d be calling it “stubborn.”

I love that it doesn’t satisfy expectations! No ooh-la-la fruit; indeed nothing blatant about this wine at all. At first glance it’s a subtle, structured and vinous wine yet with a gliding kind of lightness. But the wine straddles a fence, and I wonder whether it would better occupy one side or the other; either go on and make it “charming” or go all out to make it as slatey and mineral as possible and trust that fruit will attend to itself.

Selbach-Oster Pinot Blanc

2019 Pinot Blanc Trocken

Tasted from an opened bottle (on the day it was opened) back in June, and it strikes me as a superb vintage of a really surprising success for them, and that’s in part because it’s not bone-dry, and because it combines a slatey twang with a remarkably deft use of wood. And in this case, a lusty fruit statement that’s also sea-salty and even seems to have a little sponti element. I have long thought this was among the world’s more interesting (and tasty) Pinot Blancs, much to my surprise (as Johannes won’t hesitate to tell you…) when I first tasted it in 2015.

2019 Pinot Blanc Reserve

It’s in a heavy “significant-looking” Burgundy bottle with a wax blob in place of a capsule. Nor does it say “Trocken” on the front or back labels.

I WISH THE BOTTLE WAS NOT SO HEAVY. IT DOESN’T NEED TO BE.

The wine is ambitious, and most of its ambitions are realized. I have the sense that my old pal Johannes wants to make his bucket-list wines now—the Pinot Noir, this, an orange wine he made a couple years ago, the upcoming Gewürztraminer … or maybe it’s the yawp of the young’uns and the envelopes they like to push. But I do know Johannes has a “thing” for big Chardonnays, to which this wine alludes.

Alludes, but doesn’t copy. It’s grown in the slatey Schlossberg, and it saw no new wood. It likes a round wide-ish glass. It has a charming fruit that’s slow to emerge. Put it this way: I had a 2018 St-Aubin Les Fionnes from Hubert Lamy last week, and that was good and this is better. It feints toward the smoky-oaky genre but keeps pulling back to a saltiness and structure girdling this subtle sweet-hay kind of fruit. I’d really like to make a shrimp risotto with a fresh stock from the shells and a few too many threads of saffron.

I’ll baby this for a few days and watch how it develops. Right now I’m feeling impressed with the audacity and generally happy with the booze, but I have a niggling sense that its reach exceeds its grasp. Tasted again—and very much enjoyed it with food—I do think it is—“ambitious”