by Lisa Granik MW

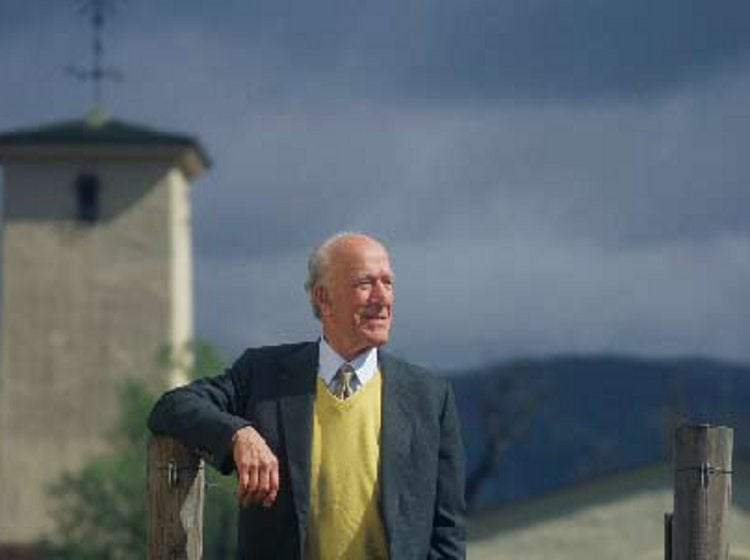

A chapter of American wine history ended on May 16, 2008, with the passing of Robert Mondavi. For more than 70 years, as winemaker, marketer, and leading champion of California wine, Mondavi had vision, passion, and a pursuit of excellence that inspired fellow travelers to produce wines that, as he liked to say, could share the table with the greatest wines of the world.

Mondavi’s parents, Rosa and Cesare Mondavi, had emigrated from Italy’s Marche to Minnesota, where Robert was born on June 18, 1913. Cesare originally worked as a miner, then a grocer, but taking advantage of conditions under Prohibition, he established C Mondavi and Sons, a successful fruit-packing business; Robert and brother Peter worked with their father shipping grapes from California to home winemakers in the east. By 1923, the family had moved to Lodi, which at the time was the center of the American grape-growing industry. After graduating from Lodi High School, Robert enroled at Stanford University, graduating in 1936 with degrees in Economics and Business Administration, yet also with more than a passing interest in the wine business. That summer, he took what he called a “crash course” in viticulture and enology at the University of California, Berkeley, and started working for a St Helena bulkwine business. It didn’t take long for Mondavi to explore ways to improve wine quality; by 1937, he had already established a small laboratory where he ran experiments for that purpose.

Mondavi married his childhood sweetheart, Marjorie Declusion, in 1940 (the couple later divorced). Their first son, Robert Michael, was born in 1943, the same year that Robert persuaded his father to purchase the Charles Krug winery. Cesare acceded, with the proviso that Robert and Peter work together to grow the business. This they tried to do, but as the years went on, disagreements and resentments mounted. Robert, a master of public relations, was extroverted and, in his brother’s view, extravagant in his aspirations and his spending. During the 23 years they ran the winery, Robert traveled to promote and sell the wine; he would return from his travels urging Peter to adopt various techniques to improve the wines. Conflict came to fisticuffs in 1965, and when the family stood behind Peter, Robert was dismissed.

Unemployed, down but not out, Robert secured investors and bought 11.6 acres (4.7ha) of the historic To Kalon vineyard, on which he built Napa Valley’s most significant new winery since the late 1930s. The striking, mission-style winery was only the first manifestation of the changes Robert Mondavi would usher in. He introduced “flange-top” bottles; coined the term “Fumé Blanc”; first advocated stainless-steel fermentation tanks; and later, wooden fermentation tanks and élevage in French barriques. The Robert Mondavi Winery became a training ground for many of America’s most respected winemakers, such as Warren Winiarski and Zelma Long. Similarly, at a time when many winemaking communities remained insular, Mondavi initiated international joint ventures: with Baron Philippe Rothschild to establish Opus One; with the Frescobaldi family of Tuscany to produce Luce; and with Eduardo Chadwick for Seña.

Unfortunately, the ongoing family feud metastasized into acrimonious litigation. At its conclusion, in 1979, the family was ordered to pay Robert $5 million for his interest in the Krug winery and the rights to a 5.5-milliongallon winery in Woodbridge, California. This facility was used for lower-priced wines from the Central Valley called Woodbridge; critics, including Robert himself, later sniped that it tarnished the original brand. By that time, Robert’s children all worked for the business: Along with Michael, Timothy ultimately became head winemaker; Marcia Mondavi Borger worked in marketing and promotion; they all sat on the board of directors. In a decision Robert later regretted, the family took the company public in 1993. But the younger generation was no better able to work harmoniously than their forebears, making it difficult to respond as the elegant flagship wine, the Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve, seemed overshadowed by newer, flashier, and more alcoholic wines.

All the while, Robert increasingly ceded more control to his sons, freeing him to his next passion: philanthropic pursuits that promoted the fine arts, redefined to include wine. Synchronous with his vision of Napa Valley as the hub of an American wine renaissance was his concept of a cultural center in downtown Napa. Robert, along with his second wife, Margrit Biever Mondavi, led the campaign to develop COPIA, The American Center for Wine, Food & the Arts, and he donated $20 million himself. Other recipients of his largesse included the University of California, Davis, as he donated $25 million to establish the Robert Mondavi Institute for Wine and Food Science, as well as a further $10 million to complete the campus’s performing-arts center.

Unfortunately, by the beginning of this century, dissension within the family and the board regarding the company direction collided with a soft economy and declining revenue. After difficult negotiations to restructure the company, the board decided in 2004 to sell the entire corporation to Constellation Brands, who had offered a takeover bid of $1.35 billion. While Constellation retained Robert as chairman emeritus for his division, he was effectively out of the wine business until 2005, when he joined Timothy, Marcia, and their families in a new Napa Valley Bordeaux-blend venture, Continuum, which will soon be produced exclusively from a vineyard on Pritchard Hill.

Robert ultimately reconciled with his brother Peter, and they produced one final barrel of wine, which sold for $401,000 at the 2005 Napa Valley Wine Auction. Peter survives him, as do Margrit, his children, and nine grandchildren.