It was for the outbreaks of unbounded jollity that the Puritan movement of the 17th century in England put a stop to Christmas. For a decade and a half, from 1644 to 1659, the traditional celebration was effectively banned, because what ought to have been the solemn observance of the birth of the Redeemer had turned into little more than a pagan orgy of consumption. Mass dancing and drinking were the incriminating evidence of this tendency, in which preachers of the day saw a thinly veiled return to the Bacchic sacrificial festivals of antiquity.

In The Anatomie of Abuses (1583), the pamphleteer Philip Stubbs had pointed out that Christmas seemed to tempt honest citizens to backsliding. “What dicing and carding, what banqueting and feasting, is then used more than in all the year besides?” The problem with masques and dramatic presentations is that they were the perfect chance for anonymous crime to be committed, the insolence of which was provoked by the volumes of alcohol taken.

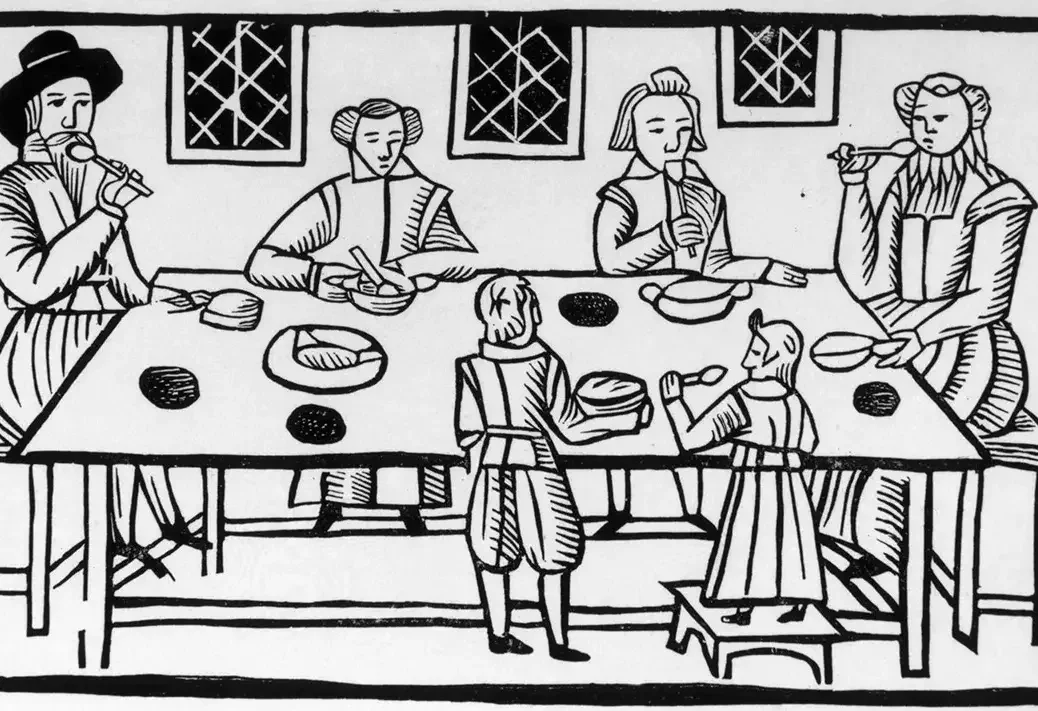

By 1632, the Puritan lawyer William Prynne, who was acutely sceptical about the value of all church festivals, deplored Christmas as the occasion of the worst behaviour. The English were incapable of celebrating any festival without “drinking, roaring, healthing [toasting], dicing, carding, masques, and stage-plays.” The average foreign infidel, contemplating the Christmas season, would conclude that the divine person whom it honored was evidently “a glutton, an epicure, a wine-bibber, a devil, a friend of publicans and sinners.” Which is of course exactly what was said of him contemporaneously (Matthew 11:19).

The Puritan plot against Christmas

The chance to put an end to this was seized in 1644 when Christmas Day fell on a Wednesday, the last Wednesday of each month being traditionally an occasion for penitence. Initially, the Commonwealth government was not disposed to be quite so forbidding, but there was an unmistakable historical link between gluttony, bibulousness, and the opulence of kings. One only had to look to the historical record to take note of the gigantic revelries put on over the 12 days of Christmas 1482-83 at Eltham Hall by Edward IV, when around 2,000 guests were daily regaled with all manner of roasted fowl, including peacocks splendidly dressed for the table in their own plumage, and hogsheads of imported wines. Was it entirely coincidental, a Puritan was entitled to ask, that it would be the King’s last Christmas?

In the Puritan temperament, which has by no means been confined to the English 17th century, what is most detested is the spirit of subversion that seems to lurk in alcohol. The many festivals that overturned the social hierarchy, from the Roman Saturnalia to the satiric inversions of Twelfth Night, were emboldened by drink, but even the most apparently innocent of practices, such as wassailing, seemed to body forth the impertinence that led poor peasants to demand acts of largesse from their betters. Wassailers who felt they had not been sufficiently rewarded would occasionally force a drunken ingress at the manorial hall. As the West Country carol points out, those who expect figgy pudding “won’t go until we get some,” and a little mulled wine on a frosty night helped matters no end.

A Puritan across the pond

Barely had the ban on Christmas been rescinded in England with the Restoration of the monarchy than it took root in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. There, it endured for an overcast 22 years, enforced by swingeing fines. The same connections between riotous paganism and the celebration of the birth of the Christ child were noted by authorities such as the Revd Increase Mather, who observed that the chief component of the festivities was “excess of Wine, in mad Mirth.” It was not—and this was surely the clincher—what Jesus would have wanted.

As the two aspects of Christmas diverged over the centuries of the Common Era, the link between revelry and piety was broken. Their severance lives on today in those who deplore the shallow matrerialism of Christmas, the overdrinking, overstuffing, the neglect of work not merely for one glorious festive day, but for something close to a fortnight. This of course was the exact period that the Christmas holiday was intended to run, from the historically baseless date of 25 December to the twelfth and final night. If there were ever a time in the church calendar to let go, this was it.

We can be sure that Dickens’ Mr Scrooge is earnest in his wholesale reform on Christmas morning, not merely by his purchase of an enormous turkey for the Cratchit family, but for his eager anticipation of an afternoon bowl of steaming-hot, spiced and oranged Port punch.