Reviewed by Stuart Walton

The only radical intoxicant still permitted to the mass of humanity, other than where religious interdiction has declared it beyond the pale, alcohol remains an elusive cultural entity. To be sure, sites for its production, sale, and consumption proliferate across the face of most of the globe. It has settled deep into entirely heterogenous cultures throughout recorded time and prior to it — even where its prime materials cannot be grown; even where a mass of social restriction and proscription has arisen to curtail its use. It is one of the indispensable elements of the rite of passage to adulthood, as well as support and comforter, sacrament and sustenance thereafter. Arraigned for depraving morals and dissolving social order, it nonetheless marks the cycles of life, ringing in the New Year and ringing out the day’s labor as occasion stipulates.

Its elusiveness in the face of such near ubiquity derives from its always being more than just alcohol. Other than when intentionally defying decorum, what people drink is not “alcohol” but one of its representations — wine, cocktails, a few beers, an appetizer or eye-opener, sharpener or stiffener, Dutch courage, “something stronger,” or simply “a drink.” What is being eluded, among the various functions ascribed to it, is the primary role of alcohol as an intoxicant. The chief reason for drinking it is its biochemical action on the brain, once the liver has been required to metabolize too much of it at once, the relatively simple physiological process from which a vast proportion of human social development and cultural complexity have been elaborated.

A multidisciplinary approach

What this admirable essay collection attempts is effectively a multidisciplinary approach to drinking studies, conceived along the lines of the historiographical fashion for social biography. Drinking is explored under four divergent headings: in its relationships to society, to material culture, to national identity, and to the individual. The chief benefit of such a strategy is that social and thematic continuities emerge between different periods and cultures, continuities that lie dormant when a topic is considered only in localized contexts or in a specific era. Structural anthropology once attempted something similar, before the advent of post-colonial studies, with its insistence on respect for the unique exceptionalism of every culture, stopped it in its tracks.

Tavern fraternities

Proceedings open in the Florence of the late 16th century, with David Rosenthal’s reconstruction of the life of tavern fraternities and the moral onslaught to which they were beginning to be subject in the early modern city. When, in 1593, Bastiano de’ Rossi stood before the august assembly of his fellow literati in the Accademia della Crusca, to defend the tradition of carnivalesque subversion in which the Florentine taverns played such a focal part, he offered the notables not just a last-gasp plea on behalf of a way of life but a paean to wine itself: “Oh precious liquor, for that is what you truly are. With your ruby colour you cheer the hearts of the living, with your aroma you comfort them, with your taste you revive them. What can one do without you? What can one say? What can one think?”

The reform of the taverns was a plank of Tridentine policy, since the Council of Trent had earlier in the century declared them to be places “where God does not live.” Bastiano’s apologia highlighted the social fluidity to be seen in them, when different orders of society came together in the fellowship of drink, thereby rehearsing that broader fellowship of which the ecclesia was still, officially at least, in favor. In the typically subversive form of a dream narrative, Bastiano recounted the various punishments that tavern workers would, in an ideally inverted world, hand down to the supercilious likes of the Academicians. These would include the “terrible sentence” of being served nothing better than the Ligurian swill of Cinque Terre — or worse.

Less fluid class boundaries

Paul Jennings’s history of the 1904 Licensing Act in the UK records the process of natural wastage that saw the numbers of public houses decline significantly throughout the final quarter of the 19th century. Once beerhouses were returned to the control of local magistrates, their licences were deliberately not renewed on expiry in many areas, in large part as the result of government concern about the “Drink Question.” The pub, once a place of polite refreshment and sociability in the era of passenger road transport, was dealt a socially transformative blow by the coming of the railways, which denuded them of their fluid class boundaries and left them largely as places of working-class resort. Those who have traced the manipulative containment of public drinking culture in Britain no further back than the emergency licensing provisions brought in during World War I ought to find this earlier evidence of social control unignorable.

Froth blowing and philanthropy

Ye Ancient Order of Froth Blowers, a short-lived British interwar organization devoted equitably to charitable works and the appreciation of beer, its story told here by David Muggleton, should remind the reader that the national taste for the invention of tradition runs deeper, if sometimes less durably, than Morris dancing. The Froth Blowers organized outings for deprived children, as well as promoting more salubrious drinking venues, and their rapid passage into historical oblivion was the mark of a moral shift that, in the Protestant world at least, would no longer countenance a link between drinking and philanthropy. In Catholic Europe, deeper historical roots and a less recriminative temper enabled its survival, down to the annual Hospices de Beaune auctions of the present day.

Nostalgia

Under the rubric of material culture, Shaun Mudd shows us some Roman drinking vessels inscribed with hortatory mottos (“Don’t be thirsty!”), and then Christopher Rountree and Rupert Ackroyd take us on an insightful photographic tour of the nostalgia-steeped interiors of a number of JD Wetherspoon pubs, where patrons can forget the prices and the blurping of the electronic tills in the various imaginative ambiences of the private library and the old-time railway compartment. The gentrification of the pub that began in the late Victorian era thus continues in the age of alcopops and microbrews.

National identity

Drinking styles are clearly as definitive of national identity now as they were when they drew bold boundary lines between the Polish social classes of the 18th century, as explained here by Dorota Dias-Lewandowska. Deborah Toner’s exploration of the cultural interdependency that alcoholism and perceptions of national decline came to acquire in the Mexican novel at the turn of the last century is a wholly fascinating study, which suggests that self-castigation in the matter of problem drinking is not a uniquely Anglo- American habit. By 1900, alcoholism was being defined in Mexican literary tropology as threatening the very existence of the nation.

Self-definition

Each of the final pair of essays looks at how individuals are enjoined to self-definition through drink. Rochelle Pereira examines (sadly without visual aids, presumably for copyright reasons) the press advertising campaigns mounted by two of the principal North American distillers to promote whisky to a type of African-American male consumer conceived in marketing executives’ minds. A trajectory of vanishing condescension can be traced in the changing depiction of black men as butlers attending to the requirements of discerning white employers into aspirant consumers in their own right, role models of social achievement.

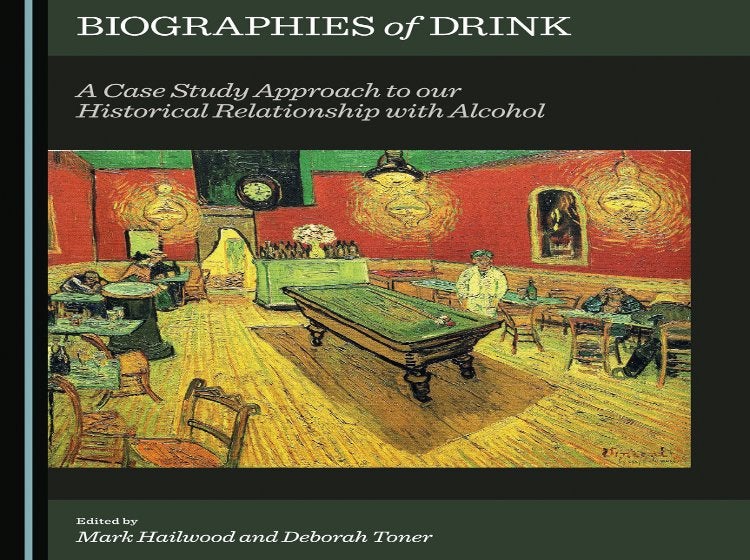

Lastly, Steven Earnshaw examines the transformation of habitual solitary drinking from the emblem of personal tragedy into which Victorian temperance had cast it, to an adjunct of the self-fashioned authentic personality of the modern age. Over the century that leads from the overlit purgatory of van Gogh’s Night Café (1888), via the café bars of the existential novel, to the drink poetry of the contemporary Scottish writer and musician Don Paterson, serious drinking has grown into a practice that might well define the late-capitalist self. No longer simply a more or less dysfunctional behavioral tendency, it is one of the constitutive components from which the modern individual may be constructed. Standing at several removes from a society that prescribes normative drinking patterns, and yet simultaneously a product of such a society by his very resistance to it, the existential drinker seems to ratify the reconnection of alcohol with the changing human condition that it did so much to set in motion.

An ironically medicinal elixir

Taking Earnshaw’s cue, one might adduce a pair of slender novels published in unwitting contiguity in 1939, which amply furnish proof that intemperate drinking had become the sustenance of the unreconciled ego in a society lurching toward its nemesis. Both set in Paris, Joseph Roth’s Legend of the Holy Drinker and Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight are respective delineations of male and female existential drinking, where every next glass is another stage in the ego’s dereliction and, at once, the ironically medicinal elixir by which it might be conformed to the darkness of the times.