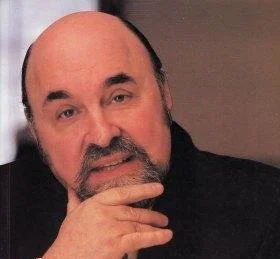

The passing in September 2023 of Nico Ladenis, one of the prime movers of the revolution in British gastronomy that took place in the 1980s and 1990s, was the occasion for much gustatory nostalgia.

As the final ebbing of nouvelle cuisine took place in London and the provinces, Ladenis’ cooking seemed to point the way forward. It owed a demonstrably large debt to the principles of classical French cuisine—an arch-enemy of food and wine snobbery, Ladenis nonetheless wrote his menus for many years entirely in French—but what he jettisoned was the delicacy, the subtle white sauces that tasted of presque rien, the toning down of vegetable pungency, and the cautious integration of seasonings. Ladenis dealt in fortissimo flavours, astonishingly concentrated essences of each ingredient, so that everything, from the truffled green leek that dressed the duck liver terrine to the tiny globe of livid red raspberry sorbet that accompanied a slice of lemon tart that was singing with citric intensity, had the impact of a Force 10 gale.

It was not just the approach to food that Ladenis revolutionized. Although he and his wife Dinah-Jane, who managed his restaurants with unflappable aplomb, hardly drank at all, he had very defined views about how wine should be treated in the restaurant context. He had an unerring nose for British hauteur, which manifested itself never so clearly as in the business of wine appreciation. In his first book, My Gastronomy (1987), one of the classic texts of its era, he recalls with horror the unhappiest period of his career at a place in Shinfield, a gentle suburb to the south of Reading in Berkshire. The venue had a separate bar, which, long before the public smoking ban in the UK, would be reliably clouded with the grey fug of people swilling perpetual gin-and-tonics. The G&T became one of Ladenis’ abiding bêtes noires, his blood coming to a gentle simmer at the sight of people knocking it back with the foie gras.

Blithe innocence and awful posturing

The problem was that, where customers did want to drink wine, there seemed to be nothing between the blithe innocence of those who knew nothing about it, and those who made themselves ridiculous with the “awful posturing” by which they let everybody else know it. “[M]any English wine lovers probably know more than the average Frenchman who is quite content most of the time to drink nothing more than vin de pays,” he wrote. Much of this expertise, though, was bogus. People who send wine back in restaurants, he believed, were mistakenly rejecting wine that was simply not to their taste, as opposed to actually faulty, as the wine merchants who supplied it would “invariably” confirm. The full connoisseurial performance was a consummate aggravation: “The elaborate ceremony, the gurgling and slopping many so-called wine connoisseurs indulge in quite honestly leaves me cold.” Where it didn’t produce behind-the-scenes giggles, that is.

These complaints may in themselves seem rather dated now, in the era of wines by the glass, unfined and unfiltered wines, controlled-oxidation wines, and wines made in concrete egg fermenters. They were also worth setting against the context of the actual wine lists at the premier London venues of Ladenis’ later career. At Chez Nico on Great Portland Street, or within the Grosvenor House Hotel on Park Lane, the wine lists were as classically constructed, as replete with pages of mature vintages of the French classics, as they were in the grand hotels and Le Gavroche. His sommeliers were always superb, on hand to make alternative suggestions that would suit particular dishes to perfection. Best of all, they refrained from replenishing the glass level after every other sip, a habit that was then still a sine qua non in British catering.

Despite the plutocratic heft of many of the mark-ups, the wine lists of this formative era in restaurant dining very much pointed the way to the great upheaval that was to follow. They brought into widespread public consciousness for the first time the idea that wine and food were made to go together, complementing and enhancing each other symbiotically, so that, taken alongside each other, they added up to more than the sum of their parts. In that first book, Ladenis still hews to some of the since-exploded customs of matching—no wine goes with smoked salmon, chocolate is the dark destroyer of even the sweetest wines, and so forth—but the wine suggestions for the sample menus are mostly very sound. The unnamed Cockney millionaire who was proudly drinking his way through a cellarful of Yquem 1947 with whatever he ate, “even kippers or bangers and mash,” Ladenis shudders, was gradually giving way to people who understood the principles of taste, and who were interested in trying wines from California, Australia, and New Zealand, rather than heading straight towards another Sancerre or another St-Emilion.

For his role in this transformation, as much as for his superlative cooking, Ladenis deserves to live on in historical memory.