The New Year always begins with pruning the vines, an act that symbolizes the start of a new growing season. It is a laborious task in the biting cold and winter gloom, but it heralds a new start in the vineyard, and thoughts turn to the vintage to come. By early 2008, after three years of hard preparatory work, we were up and running with the vineyard entering full production, a functioning winery, and our single red wine, Pedra Basta, receiving plaudits on international markets. We featured among The Wine Society’s “Buyers’ Favourites.” (“Every year The Society’s buyers swirl, sniff, sloosh, and spit thousands of wines. This is about the ones they swallow.”) We were also gaining listings in some top restaurants like Les Faunes at the Reid’s Palace Hotel in Madeira and The Fat Duck at Bray near London.

Then came a local setback. I was summoned to appear at the tribunal in Portalegre, accused of polluting a local water source. There’s a saying in the trade that “it takes plenty of water to make good wine,” and wineries create huge amounts of waste. We had run the entire 2007 vintage with a provisional fossa (septic tank), because the licence for the construction of a water treatment station (the so-called ETAR) had not been granted after more than a year in the pipeline (pardon the unintentional pun). There were fossas much closer to the water source than ours, and I did not believe that we were in any way guilty of a crime — besides which, there was absolutely no proof. I engaged a lawyer in Portalegre, who happened to be a leading local communist. As he showed me into his office, he said, “We only turn left in here.” He briefed me just before the hearing. “Remember,” he said, “that a Portuguese court is one of the safest places you can be. I know the judge, and you will be all right.” The court turned out to be a room filled with mismatching desks and office chairs set out in a U-shape, and the judge was a woman in her early 30s. She came over to me before the hearing, shook me by the hand, and chatted about wine. Various testimonies were read out, including one from the National Republican Guard, who had been called to the scene of the incident. But it was agreed that there was no proof, and therefore there was no case to hear. Justice was done, to my great relief! After this most unwelcome and potentially costly distraction, it was time to focus on the vineyard and our wines once more.

The growing season in 2008 began with a long, dry spell, then in May and June the heavens opened. Fortunately, the weather remained relatively cool in the serra, and an outbreak of oidium (which did great damage elsewhere in Portugal) was largely checked. Flowering was uneven, which reduced yields, and with plenty of groundwater to draw on, our vines were able to withstand the heat of the summer. Some more heavy rain fell at the start of September — a promising precursor for a vintage I then had to miss. Our third child was due around the middle of the month, and Isabella Maria Mayson was born at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield, England, on the 25th. In the meantime, my business partner Rui Reguinga and vineyard manager José Luís Marmelo took total responsibility for the winemaking when our estagiário (cellar hand) left on the first day of picking. We were all thankful for a small harvest.

The end of the harvest coincided with the meltdown in global financial markets. After a few months of sleeping well following the resolution of the fossa case, I was woken every night by a crying baby then kept awake by news of plunging global stock markets. I returned to Portugal in early November with a profound feeling that, though it may look much the same, the world was a changed place. My Portuguese business friends were astonished at the effective nationalization of three British banks (all the Portuguese banks having been nationalized for political reasons during the revolution in 1975), and I even received a certain amount of sympathy for the UK’s plight. At the time, Portugal seemed to be relatively unscathed, but as one friend said to me, “We are used to having recessions here.” But something told me that all the confidence of the past decade was misplaced and that this was going to be different. In the short term, with sterling’s slide against the euro, the retail price of Pedra Basta (so carefully positioned in the UK at £9.95) quickly increased to £12.50.

The 2008 vintage looked to be our best so far. I find the best time to taste young wine is before a meal, preferably before breakfast, when your senses are at their sharpest. With the malolactics mostly complete, I got up early on a cold, clear November morning to compare the 2007 and 2008 vintages, both still in barrel. The ’07s had settled down well. The Trincadeira was soft, sweet, but rather lightweight and will have to be compensated by some delicious casks of vinha velha (from the old vines). Thirteen casks of Aragonez and young-vine Alicante Bouschet were also looking good: nearly opaque in color, with plenty of soft, sweet fruit backed by firm tannic grip and well-integrated new oak. With just half our expected yields in 2008, the young Trincadeira vineyard that had performed so poorly in previous years now proved its worth and has made some good wine; fresh with crisp acidity, good purity of fruit, and spicy length of flavor — just how it should be. The older vines had also performed well in 2008, but there would not be enough to produce our first prestige.

The following spring, Rui and I spent a day in the adega making up the final lote for the 2007 Pedra Basta. It came down to a choice between Lote A (which represented approximately 16,000 bottles) and Lote B (nearly 14,000 bottles). Lote B (which contained less Trincadeira) got my vote for its aromatic, ripe yet crunchy fruit character, as well as for its structure and firm, sinewy length of flavor. So, we declassified the equivalent of 2,000 bottles for our so called Pedra F blend, which is sold to a local restaurant. But I felt pleased with the 2007 Pedra Basta, which is much closer to the style of wine I had envisaged when I bought the vineyard, showing restraint, finesse, and the integrity of a more moderate growing season. A bottle of the ’07 uncorked in April 2013 showed how well the wine is standing up.

Adega party

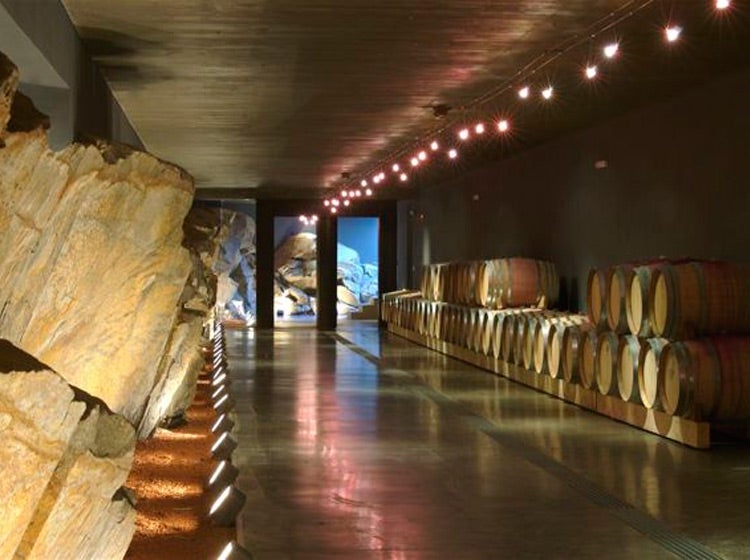

The builders having moved on, June 6, 2009, was the date set for the official inauguration of our new adega (above). People were due to come from all over Portugal (you never quite know who is going to turn up), and a few Brits, fearing the renowned summer heat of the Alentejo, stayed overnight at the Pousada at Marvão, this being the highest and coolest place. Unfortunately, on the day of the inauguration, rain lashed down, and the Serra de São Mamede remained semi-shrouded in dark gray cloud. Still, there is a saying in Portuguese: boda molhado, abençoado (“a wet wedding is blessed”). We had a good party, despite the terrible weather, with a buffet of locally produced food including cheeses, enchidos (sausages and hams), rebuçados de ovo (delicious egg sweets), and the most wonderful cherries (from nearby São Julião) that anybody could ever hope to taste. The president of the Câmara Municipal de Portalegre made a generous speech, and we had every reason to feel proud of what we had achieved so far.

Two new wines

But there was still so much more to do. We had only one wine out of the three envisaged in our business plan. The 2009 vintage came to the rescue, providing our two new wines. It was an early harvest. After an exceptionally hot August, we began picking on September 2, when the tetchy Trincadeira was already approaching 16° Baumé. But there was a happy atmosphere in the winery, with a good team of singing cellar hands and fermentation aromas that seemed to be the harbinger of good wine to come. (I recall the late Bruce Guimaraens — winemaker for Taylor and Fonseca — telling me back in 1985 that you could sense a promising Port vintage by the smell of the grapes in the lagar.) This was the year that we took our first meager pickings from the young Syrah, Viognier, and Touriga Nacional vines that I had planted in 2006. It was a tiny crop, most of the grapes having been green-harvested to help the vines establish themselves, so we threw all the grapes together to ferment in one vat. The resulting wine proved to be a fortuitous accident, and the varieties seemed to complement each other well. Touriga Nacional has a pronounced floral character that, on its own, can be both one-dimensional and slightly overpowering at the same time. The Syrah (more Rhône-like than Shiraz), which made up 40 percent of the blend, sat calmly on the Touriga, producing an aromatic yet vibrant, spicy wine. The Viognier was just the salt in the cooking. But it threw up the dilemma of what to do with the wine. It was much too distinctive to enter the Pedra Basta lote , so we decided to bottle it separately, young and with minimal oak aging for the fruit to express itself. We christened it Duas Pedras (“Two Stones,” after the local schist and granite) and launched it in Portugal and the UK in 2010.

With all our grape varieties performing well in 2009, we set aside a few barrels of a field blend from the older vines with the objective of making our first prestige red, Pedra e Alma (“Stone and Soul”). Eighteen months later, in May 2011, we were in a position to taste our way through 11 225-liter casks, all new French oak but from a number of different coopers and with varying levels of toast. There was a real difference between Seguin Moreau (restrained), convection-toasted barrels from Chilean cooper Odysé (broader tannins, more structure), and Taransaud (fresher, showing more acidity). The final Pedra e Alma lote, bottled in early 2012, is a complementary blend of all three. Straightaway, it was selected by Julia Harding MW as one of her top 50 Portuguese wines: “Sweet chocolaty oak flavors, really dense fruit underneath. Very smooth and very long, needing time for the oak dominance to fade and allow the fruit out more. But it has that lovely effortless concentration and harmony of an old-vine blend — density, freshness, and polished tannins. Very moreish. [Drink] 2014-2020.” Pedra e Alma couldn’t have had a better start in life!

The launch of our two new wines coincided with a marked deterioration in the Portuguese economy. In the spring of 2011, with the country close to bankruptcy after nearly two decades of EU-instigated excess, the government collapsed and the so-called troika (IMF/ECB/European Commission) rode in to the rescue. Although Portugal has been a model pupil, the effect of financial austerity on the national economy has been devastating, and wine producers have taken more than their fair share of the hit. The Portuguese are accustomed to eating out, but when the tax on food and wine consumed in restaurants nearly doubled to 23 percent, businesses began shutting their doors. Everyone owes money, and the banks have dug their heels in and are generally unwilling to lend. At the end of 2011, our Portuguese distributor told me without any hint of exaggeration that “if I stopped selling to clients who owe me money, I’d have no clients.”

The economic situation in Portugal has hit us very hard. When we set up Sonho Lusitano Vinhos, we planned on selling around half our production on the home market, but in 2011-12 our domestic sales fell to around one fifth. It reassures me to hear from other, long-established producers that we are not alone, making it all the more urgent that we export more and farther afield. As much by luck as by design, we have kept supply and demand in balance, building loyal markets in Belgium, Switzerland, Ireland, and Brazil, as well as in the UK. But one crucial market has proved very hard to crack. We had been trying, unsuccessfully, to sell to the USA ever since we launched our first wine in 2007. Importer after importer turned down our wines, offering a variety of different reasons: price, can’t sell Portugal, too much oak, too traditional…

In January 2013, the outlook seemed particularly dismal. Tomba Lobos, our wonderful restaurant in Portalegre closed its doors for good, and DrinkPor, the local drinks wholesaler went into liquidation. Then, almost out of the blue, we received an order from a well-known importer in New York: Skurnik. We prefer to work with importers who see Portugal as part of a wider portfolio rather than as an end in itself. I have just returned from Skurnik’s annual tasting, where it was uplifting to see our wines standing alongside names like Vega-Sicilia, La Rioja Alta, Peter Michael, and Bonny Doon. To add to the good news, Duas Pedras 2011 has followed Pedra e Alma by being selected by UK wine writer Olly Smith as one of this year’s top 50 Portuguese wines. Duas Pedras has become our austerity red, and selling at two thirds of the price of Pedra Basta, it has probably cannibalized sales of the latter to an unknowable extent. But Pedra Basta has built up a loyal following and is continuing to reach all the right places. In November 2011, it was served at a dinner hosted by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge at St James’s Palace.

Despite having been blown off course by the recent economic headwinds, eight years after having purchased Quinta do Centro we are not very far from where we envisaged we would be at the outset. I haven’t been able to build on the tourist potential as I had hoped, and I am still sitting on some dilapidated properties in need of investment. It has been an exponential learning curve, poacher turned gamekeeper, wine writer to wine producer. Buying and running a vineyard means you become a bit-time farmer, environmentalist, politician, economic commentator, winemaker, and salesman — sometimes without even realizing it. There have been times when I would freely admit that the dream had turned into something of a nightmare. But I have my patch of Portuguese terroir and three red wines from one of the most captivating parts of Europe. I wouldn’t have it any other way.