How a drop-out conquered the wine world

It seems appropriate to begin a review of the memoir of one of the leading figures in the British hospitality trade with a bit of housekeeping. So, here goes: I can’t say I’ve come to this piece in a spirit of detached objectivity. For various reasons, reading Tasting Victory was an unusually emotional experience.

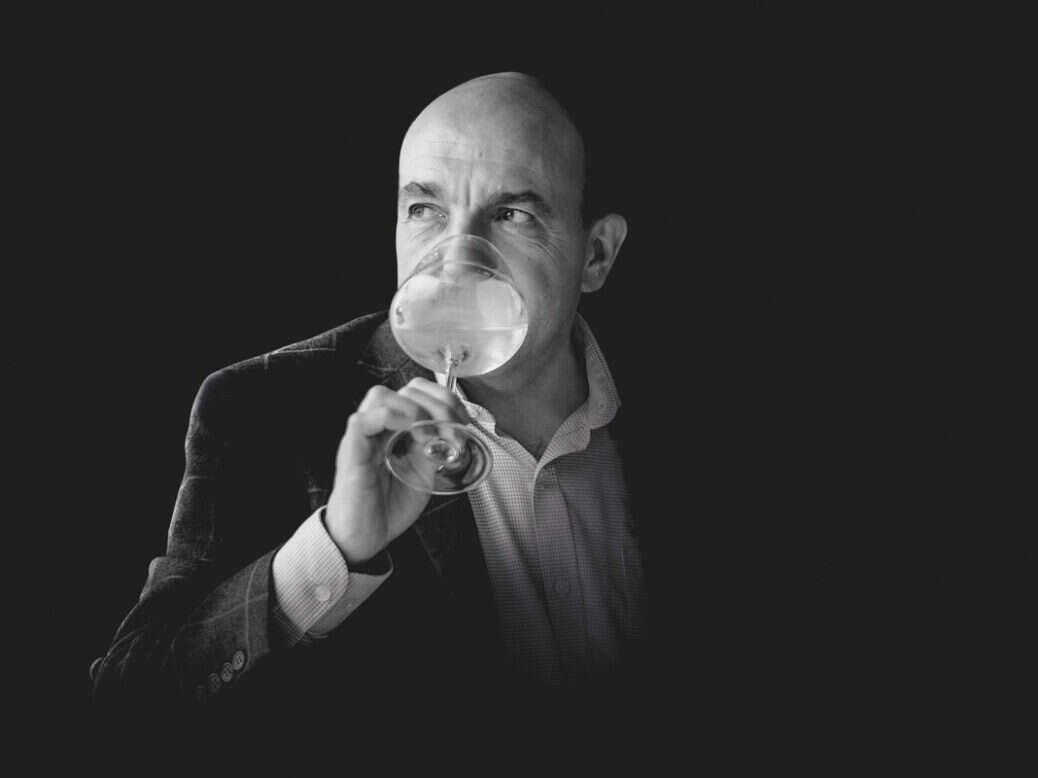

First I need to declare a personal interest. I didn’t know Gerard Basset well enough to say we were friends. But from the moment I first met him 20 years ago (an occasion that was rather more significant for me, as a young trade journalist, than it was for him, already far and away the leading sommelier of his generation), he always treated me as if we were. He made time to talk to me. In later meetings, he remembered things I’d told him from months or years before.

Mine was not an unusual experience. Basset seems to have had this effect on countless acquaintances. It explains the extraordinary outpouring of grief and affection when he succumbed to cancer in early 2019—a wave of emotion that led directly to the existence of this book, which was crowdfunded (along with a travel bursary named in his honor) after an appeal by his family and friends in the trade, reaching and then exceeding its target in a matter of days after Basset’s death (the hundreds of donors are all listed at the back of the book).

Any failure to keep emotions in check isn’t solely the consequence of my relationship with the book’s late author-subject, however. It also has something to do with the circumstances in which I read it: a time of lockdown, of shuttered restaurants, cancelled wine tastings, and furloughed or redundant hospitality workers, and when the very future of the sector was clouded with uncertainty. Would I ever eat in a restaurant, use a spittoon in public, or stay in a hotel again? In telling the story of Basset’s career in the British restaurant and wine trade, Tasting Victory provided a vicarious experience of what I was missing. But also a poignant dose of nostalgia for a world that may never return as it was.

An unusual voyage

Still, I’m pretty sure that Tasting Victory would be an enjoyable read for anyone with an interest in wine or British restaurant history even in more ordinary times. Briskly, crisply, unfussily written, it tells its tale in a largely linear, chronological way, following Basset’s unusual voyage from directionless working-class French kid, to successful English hotelier and World Champion Sommelier, and providing a nice slice of social history in the process.

For anyone who knew Basset only in his latter incarnation, the early chapters of Tasting Victory, detailing his sometimes-difficult childhood with his loving but fractious parents in Saint-Étienne and his first fumbling attempts to find a purpose in life, will be particularly revealing. Basset is unsparing on his young self as he drifts through a series of dead-end jobs, “At seventeen, however, it was not obvious that I would become someone featured in magazines,” he writes. “I had dropped out of school because of my poor marks and the only job I could find was in a local clothes shop. I had no clue what to recommend to customers and was sacked after two weeks.”

The contrast with the almost monomaniacal, driven Basset who, some 30 years later, goes to enormous lengths to win the World Sommelier Championships, is profound. Winning the championship was an obsession for Basset, and his insights into the world of competitive sommellerie in Tasting Victory are fascinating. It’s a surprisingly serious business, with the intensity of training and the pursuit of marginal gains reminiscent of preparations for Basset’s beloved Tour de France. After trying and narrowly missing out on a few occasions, Basset himself employs a mentor-cum-coach and draws on the expertise of two World Memory Championship winners before finally being crowned champion at the 2010 final in Santiago de Chile.

Basset’s competitive and academic achievements make for an impressive story on their own. After winning in Santiago, he reflects that the “drop-out from Saint-Étienne had achieved something that no other person in the whole world of wine had done before”: a hat-trick of vinous-academic qualifications (Master of Wine, Master Sommelier, and Wine MBA) as well as being the World Champion Sommelier. But what makes Basset’s life all the more impressive—and Tasting Victory all the more interesting—is that all that study and competing happened while he was simultaneously making a successful career in business.

A life well lived

Basset famously fell in love with the UK after coming to see the Saint-Étienne football team take on Liverpool and moved there permanently in the early 1980s, his career in the country coinciding with an epochal shift in British eating and drinking habits, when both wine and eating-out became mass-market pursuits.

It was good timing in other words, but Basset made the most of the opportunities that came his way. Certainly The Hotel du Vin, “a midmarket hotel/restaurant, but of great quality,” that Basset started with Robin Huston, an old colleague of his from the country house hotel Chewton Glen, initially in Winchester in 1994, was an idea whose time had very much come. By “cut[ting] down on the high luxury items and the range of services offered, but offer[ing] a great venue, excellent food and professional, friendly service,” Basset’s and Huston’s business, which opened branches across the UK as the 1990s progressed, helped shape the democratization of British hospitality, as well as providing a launch-pad for numerous influential chefs and sommeliers.

Basset is very good at conveying the excitement of setting up and then overseeing the success of Hotel du Vin as it developed into a mini-chain with sites across the UK. But he doesn’t gloss over the difficulties and risks of business life, both at the Hotel du Vin (he had to sell his car and borrow from his wife Nina’s father to get the business off the ground) and at Terra Vina, the New Forest wine hotel he set up with Nina after Hotel du Vin was sold to rival chain Malmaison for £66.4 million in 2005 (and which, after a successful beginning, was “just breaking even” by 2017). Basset is no less candid about his cancer diagnosis, which came as a bolt from the blue in late 2017. “To my surprise I did not panic or have a meltdown,” he says. “Of course, I was not happy, just philosophical.”

As is clear from the moving final chapters, which describe the Bassets’ attempts to completely restructure and rebrand Hotel TerraVina while coming to terms with the implications of Gerard’s diagnosis, Basset had to draw deeply on that philosophical attitude and resilience in the last few years of his life.

But there’s no bitterness in these pages, just an overwhelming sense of gratitude for a life well lived. “My efforts to serve other people, to choose wines that would take their meal to another level, to make them comfortable and give them a night, or a holiday, that they would remember for the rest of their lives, repaid me many, many times over,” he says. “I would do it all again.”

Published by Unbound; £25 / $29