Caveat emptor. Nobody embodies this principle more fully than Maureen Downey, the world’s foremost expert in counterfeit wines, founder of Chai Consulting LLC and Winefraud.com. Downey and her team were in London in early December to hold the world’s first wine-fraud and counterfeit-wine authentication classes for professionals and collectors. (The same presentations and courses were held in Hong Kong in February 2017.) With a long track record in fine-wine authentication, Downey honed her skills to become an established expert in counterfeit wine and has worked closely with the US Department of Justice and FBI in numerous wine-fraud cases.

Her expertise has helped bring many guilty parties to book. The ubiquity of wine fraud has turned Downey into the most outspoken voice on counterfeit wine. She is on a crusade – to stamp out not only illegal practices but also the often staggering (or even willful?) ignorance of those engaged in the legal and respectable side of the trade.

Her presentation (above), held at 67 Pall Mall, made clear that wine fraud comes in countless forms, many of which do not even involve counterfeiting, like the misselling of wine futures and fine wines by fake firms, fine-wine theft, the switching of wines in warehouses, insurance scams, and illegal import/ export. Counterfeiting itself also comes in various forms: in misrepresentation and mislabeling of grape variety, blend, origin, or vintage; in intellectual property infringement, very common on the Asian market with look-alike labels designed to dupe naive consumers; and in the adulteration of wine. Downey cautioned, “Anyone in the wine business who thinks wine fraud does not affect them is sorely mistaken.”

Downey’s main presentation, however, focused on the burgeoning amount of fakery in the secondary fine-wine market – where most money is made – and was peppered with shocking examples of brazen criminal behavior. According to Downey’s estimates, 20 percent of all fine wine traded is counterfeit, the proportion significantly higher for some retailers and auction houses than for others. She mentioned the pictures that went around the world of the fake wines seized in the Kurniawan case and destroyed in a junkyard – but, she warned, these were only the bottles that were seized; most of what he sold is still out there, being bought and sold, as are thousands of fakes brought into circulation by the convicted Belgian merchant Khaled Rouabah. She also cited instances of collectors who discovered they had been sold fakes and sold them on to recoup their cash.

While noting that wine fraud is as old as wine itself, Downey outlined the European shenanigans of fraudster Hardy Rodenstock and traced the current counterfeit boom to a number of coinciding factors: the rise of the 100-point score and the attendant phenomenon of well-heeled but inexperienced drinkers “diving straight into grands crus” without ever having drunk lesser wines. Their hunger for “insta-collections” and legendary wines and vintages meant that “price became more important than provenance.” Another factor was the rise of wine auctions, which “became legal in New York State in 1996 and normalized in the 2000s. Ebay made auctions something that we [Americans] understood,” Downey explained. “You had this environment of ‘Let’s all drink all the 100-point wines we can in the biggest bottles we can find.’ These eager-beaver guys with more money than sense were a golden opportunity for counterfeiters.”

The trouble is that it is not only overexcited newbies who get conned but also serious collectors and the people who sell wine to them. “Counterfeiters have unprecedented access to all levels of the industry,” which is now global, said Downey, with the Internet often providing a useful cloak of anonymity. Hong Kong dropping its import duties on wine in 2008 was another contributing factor, turning the Asian hub into the “wild, wild west of wine.”

Forensics and suspects

“Tasting,” said Downey emphatically, “is the least valid way of evaluating a wine. Every time you read ‘extremely youthful for its age,’ it signals that the wine may well be a counterfeit,” she said, making clear that many of the existing tasting notes for legendary old wines were based on fakes and, in turn, serve as “recipes” for faking. “Does anybody know what these wines taste of?” she asked. Her method of authentication thus focuses on hard forensics. She presented many examples of side-by-side comparisons of originals and fakes. The photograph of a fake 2013 Georges Roumier Chambolle- Musigny Les Amoureuses clearly showed the vintage stated in a much thickerframed box on the label—but without an original with which to compare it side by side, would you know? On a 2010 Dugat-Py the giveaway is an uneven cutout of the neck label: “Poorly cut-out neck tags is not something quality producers do,” Downey noted. But her immense experience of looking at thousands of bottles also allows her to detect less obvious signs. She knows when a glass color is wrong, when the paper of a label does not feel right, or when a capsule looks too pristine.

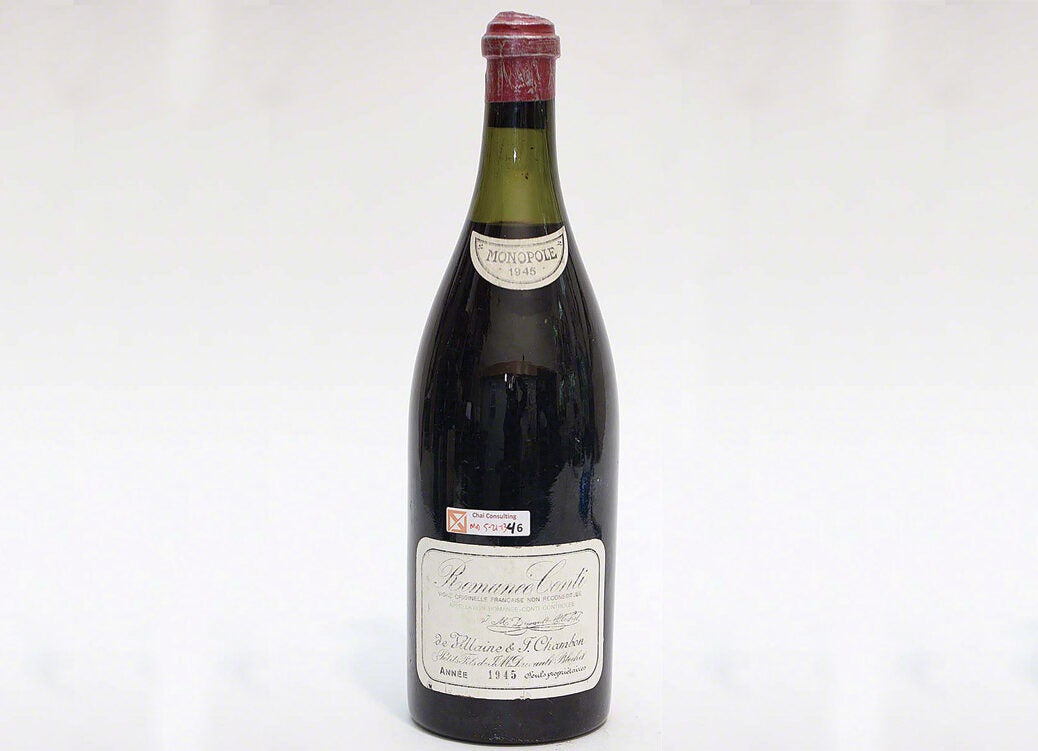

Then there is the problem of refilled bottles. Downey showed photos of the same refilled bottle of Cheval Blanc turning up at a tasting in Burgundy in 2012 and again in South Africa in 2013. Its label is clearly torn in the same places. According to Downey, certain bottles turn up again and again. She urges restaurants to destroy empties—but there also are stories of sommeliers spiriting empties away in order to sell them at lucrative prices. So-called unicorns are another aspect of fakes; these are wines that never existed, like Ponsot-bottlings by the French merchant Nicolas, or magnums of 1945 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. “I have touched more large-format DRC than was ever made,” Downey joked, before delving further into her trademarked authentication process and pointing out the mistakes counterfeiters make.

Downey stressed that knowledge and information are power. Meursault, for instance, was not designated as an appellation contrôlée until 1970, so any pre-1970 Meursault sporting “AOC” or mention of a controlled origin is a fake; as is any pre-1987 Pessac-Léognan, which until then was in the Graves appellation; or any bottles mentioning ACs before they were established in the 1930s. In terms of information, it’s worth knowing if certain domaines or châteaux produced certain formats, or if their legal structure as stated on the label is correct for the time. Vintage information is valuable, especially when it comes to whole collections: “I don’t believe in verticals,” said Downey. “Why would you keep a 1972 Mouton? Because it’s got a Warhol label, there’s that. But why keep a 1946 Mouton? It’s what you drink while your 1945 matures. It’s also important to know which vintages were not made.” Some vintage years are more likely to be faked than others: years of comets or other landmark events. “Someone recently asked me about lucky numbers in Asia,” Downey recounted. “So, if I was counterfeiting anything right now, it would be Cheval Blanc 1988.”

Each element of a bottle had its turn, and while Downey showed lots of telling photographs, she insisted that “If you want to authenticate, you need to touch stuff. Paper will tell you how old it is by the way it feels. How does ink permeate or not permeate the label? Is the amount of wear appropriate for the capsule? Has it been reapplied?” Labels are often oven-baked to give them an aged look before being applied or stained with tea to make them look old and cellar-soiled. Downey had a lovely photo of a thick stack of 1943 Clos de la Roche labels taken in Kurniawan’s “workshop.” For corks, she looks at their length, age, branding, and any signs of adulteration or scraping. “Glass,” according to Downey, “is the counterfeiter’s Achilles heel. It’s one of the most difficult things for counterfeiters to get right” – hence the market for empties. She has even witnessed different bottle heights within the same case of wine – and by the way, original wooden cases are often faked, too, or reassembled. Even sediment is faked. Bottles that claim to be “special bottlings,” such as family reserves, are also red flags that often signal fakes. Overall, consistency is very important. Downey asked, “Is it a 15-year-old face on a 37-year-old body?”

“There are only about 30 SKUs [stock-keeping units] that we are dealing with,” Downey said, showing a slide with the names of the usual suspects: the five first growths of the Left Bank, the stars of the Right Bank, the “La-Las” of the Northern Rhône, and a handful of very exclusive Burgundy domaines. Italy is represented only by Sassicaia, Ornellaia, Soldera, Gaja, and Giacosa. When talking about measures these producers take to counter fakes, she was critical of RFID chips, which can peel off and be faked themselves. Downey’s newly launched Chai Wine Vault database, which she has developed together with Everledger, uses a blockchain system and stores more than 90 data points of a wine, including its bottle, label, glass, capsule, and cork, to “create a unique digital thumbprint.” Everledger originally developed an authentication system for diamonds whose value, just like wine, relies not only on authenticity but also on provenance. It is a tool that can “create a complete audit trail” and ensure transparency in an otherwise rather murky secondary market.

Tools and techniques

After a brief lunch break, everyone was able to start sleuthing for themselves. Some of the producers’ more recent anti-fraud measures became apparent. Downey and her team brought a wide selection of fakes and a few originals against which we could compare them. Armed with a jeweler’s loupe and blue-light torches, it became much easier to spot the fakes. The wisdom of “touching stuff” became clear, too. An amazing tool in Downey’s work is Supereyes, a handheld digital microscope connected via USB to a laptop – surprisingly good value and an investment all brokers should make. It magnifies the label to such a degree that fakes become easy to spot. The green font used for “APPELLATION ROMANÉE-CONTI CONTÔLÉE” on the fake bottle was mottled and fuzzy, whereas the original was solidly colored and perfectly sharp. The difference in print quality between home-computer printed or color-copied labels and the real thing was striking. Magnified by Supereyes, the micro-lettering incorporated into the label of a firstgrowth château’s label become clearly legible while remaining invisible to the naked eye. Another oft-copied label sparkled under blue light, whereas the fake remained matt. These are just some of the ways in which producers mark originals that are not obvious to fakers. The entire exercise showed that there is a huge range of fakes – some amateurish; others very, very good.

Opening eyes

The audience comprised collectors and professionals. Marie Keep, senior VP at Boston auction house Skinner, explained why she flew to London to take the course: “There are lots of counterfeits out there, and I am here because I want to be ahead of the curve. I want to know what’s out there, I want to know how to protect my buyers, and I want to be able to assist consignors to look at their cellar with knowledgeable eyes.” What had she learned? “It’s an industry rife with lots of little things to look at. I think it’s about slowing down and moving very carefully, following your instinct and understanding why something does not look or feel right. Here we are looking at a table full of counterfeit wines, but if you are working with collections, the context goes beyond that: how the consignor has collected, where they’ve collected, what the pattern of collecting has been, and where the paperwork is – so there’s a larger picture to look at. But making sure that there is as much light shone on this as possible is going to allow people the freedom to talk about it.”

Another attendee, Laurie Matheson of Parisian auction house Artcurial, was equally aware of the amount of fake wine circulating in the secondary market. She highlighted the problem of ensuring provenance in wine: “It’s a very complex world; it’s not like a fake painting of which there is one original. Depending on the château, there can be thousands of bottles and there are always multiple sources.” What will she take away from this class? “I am definitely going to buy a blue light and Supereyes, and I am going to be even more modest,” she replied.

Ken Lamb, a private collector, came to the class with a lot of awareness already. An email he generously shared illustrates the extent of fakes and ignorance of them but also the problem of bringing people to book. It’s a message from a broker offering two bottles of 1971 La Tâche. These are very evident fakes, because the photograph shows “La Tâche” on the capsules, which DRC did not start doing until 1978. “There are only a very limited number of places where I would purchase these kinds of wines,” Lamb said, “and that particular person is not one of them. When he sent me the pictures, it immediately raised issues to me, and without giving any clues, I asked what he had done to check the provenance. The response I got was that they had looked for all the typical issues that are faked on these particular bottles – and immediately his credibility went to zero. That’s not the type of middleman I would purchase from.”

What prevents Lamb from highlighting these obvious counterfeits to the police? “It’s not clear to me that he [the broker] knows they’re frauds. It’s not clear to me that he’s informed enough even to know what to look for. So, I don’t really have a basis for doing that. The best thing for me to do is not to give him any business and to tell other people to be highly skeptical. He does not have the bottles; all he’s got is pictures.” So far, Berry Bros & Rudd in London is the only retailer that has had a team trained. Philip Moulin, of its fine-wine department, is now a certified authenticator and wise to counterfeiters’ tricks.

Downey concluded, “I hope this has opened your eyes a little. Counterfeiting is not something that started with Hardy Rodenstock and ended with Rudy Kurniawan. There should be more outrage on this from all of us.” She has made many enemies and has even been assaulted, but she refuses to pipe down. “The problem is that more criminals are seeing the benefits of wine fraud. It’s highly lucrative and relatively low risk. They can make just as much money selling counterfeit wine as selling drugs, and if they get caught they don’t spend nearly as much time in jail. At the end of the day, it’s a good business to be in if you’re a crook,” she explained. Part of going public with so much of her trademarked material now is to raise awareness and get more people certified as authenticators, so the Chai Wine Vault database becomes viable. But there is more to this than business. It’s a deepseated sense of justice that motivates Downey: “I don’t understand why more people aren’t more upset about it and why people continue to give business to vendors who have sold counterfeit and stolen wine and have done so much damage to the industry. So many people beat about the bush that someone has to be honest with our industry.” The question looming large is why the classroom was not bursting with representatives of every fine-wine retailer, broker, and auction house.