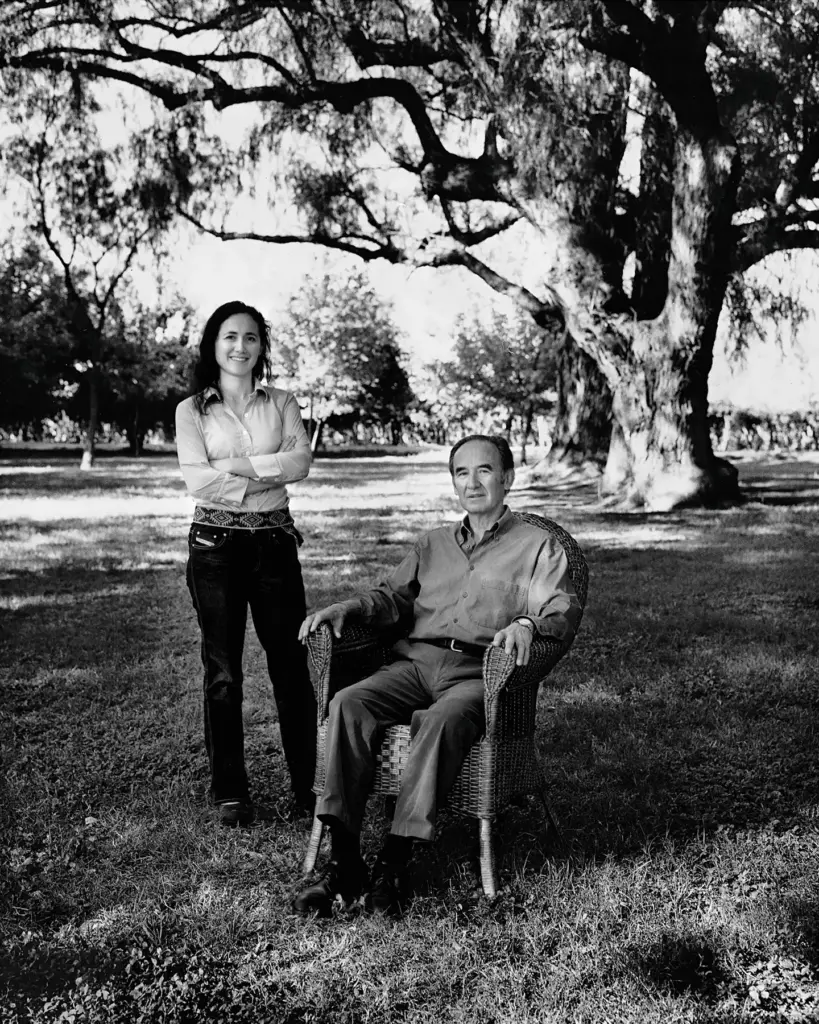

To begin a week of South America-themed writing, we turn to a classic piece, first published in WFW65 in 2019, in which Anthony Rose recounts the remarkable history of the epoch-defining Argentinian producer Catena and profiles the unassuming intellectual whose visionary ideas and business acumen put his country and Malbec on the global fine-wine map.

In the building that houses Catena’s offices in Buenos Aires, Nicolás Catena would occasionally come across Father Jorge Mario Bergoglio. Catena didn’t know who he was but felt that, by his face and his smile, this unassuming man would one day be hugely influential. We’ll never know if the man who was to become Pope Francis realized that Nicolás Catena in turn was to become Argentina’s most influential figure in wine. Indeed, to see the slight figure of Nicolás Catena shuffling in white sneakers around a college cloister in Oxford or on Berkeley campus, you would hardly guess that the self-effacing Argentine has been the driving force behind the transformation of Argentinian wine from creakingly old-fashioned and plonk-driven, to the quality industry it is today.

A clue to this complex, driven character is to be found in the comment of his great friend, the Argentinian celebrity chef Francis Mallmann: “When I first met Nicolás Catena, he looked like a priest, but he’s more like Machiavelli.” Behind the meek facade, an enquiring mind and the goal of intellectual achievement spurred on by his Argentinian mother, Angélica Zapata, have taken Nicolás Catena on a lifelong quest for discovery. To Domingo, his Italian immigrant father on the other hand, Catena owes a single-minded entrepreneurial spirit of accepting challenges and taking calculated risks. The spark created by this collision of opposites has ignited the dynamic forces behind the success of Catena as a wine company and Argentina as one of the wine world’s elite.

When Nicolás Catena, 80 this year, started working in the family business in 1963, Argentinian wine echoed the European wine tradition in its worst manifestation. The enlightened Argentinian government of the mid-19th century had encouraged immigration, but the immigrants and their children who entered the wine industry, his father Domingo among them, built smokestack wineries in the early 20th century, designed to churn out industrial-scale plonk in order to slake the thirst of a growing labor force and their families. Over time, Nicolás Catena was to work out how to relinquish the old-fashioned oxidative wines and prospect Mendoza’s desert seam for vinous gold. In 2009, he became the first South American to receive the Decanter Man of the Year Award.

The early years

After leaving Belforte del Chiente in Italy’s Marche region in 1898, Nicolás Catena’s grandfather Nicola put aside enough cash from working in Brazil and then Santa Fe in Argentina to be able to settle in Mendoza just 14 years after its connection by rail to Buenos Aires. Like many Italian immigrants, he had been encouraged to look for a better life by the enlightened mid-19th-century immigration policies of Juan Bautista Alberdi and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. “Every European who comes to our shores brings us more civilization than a great many books of philosophy,” Alberdi had written. In 1902, Catena planted a vineyard near the town of Luján just 650ft (200m) from the Río Tunuyán, some 28 miles (45km) from where the Catena Zapata winery stands today. At the time, a good year meant a big year, and Nicola chose Malbec because, after its introduction by the colorful French immigrant Michel Aimé Pouget in the 1850s, la uva francesa, as it was known, was already recognized as the best variety.

To put things into perspective, two Italian businessmen launched the La Colina de Oro winery in Maipú in the same year, with 270 fermentation tanks and 800 oak vats. They planted 640 acres (260ha) of Malbec, Petit Verdot, and Barbera in a single year, and by 1911, production had reached 11.1 million US gallons (42 million liters), making it the biggest winery in the world. The aim for wine producers, four fifths of whom were immigrants, was to keep up with the growing demand by the market for wine of any kind at any cost. By 1915, consumption had reached 16.4 US gallons (62 liters) per capita, and Argentina was the world’s sixth-biggest wine producer. According to Steve Stein, in Grape Wars, “the fact that the market largely comprised immigrants from countries where wine was popularly considered a necessary part of the daily diet (Italy and Spain) represented a key factor in winery decisions concerning quantity versus quality.”

The proud, steak-loving Nicola Catena built up the business by buying grapes and expanding production over the next couple of decades, but it was still a small player in the 1920s compared to industry giants such as Arizu, Giol, Escorihuela, and Trapiche. His son Domingo took over the business in 1936, selling his wines to Buenos Aires and provincial cities around Argentina. An astute businessman and talented tipificador, or master blender, the blonde-haired, blue-eyed Domingo was the Georges Duboeuf of his time, producing popular blends of vino común, vino reserva, and vino fino. The wines were mostly red—Barbera, Bonarda, Sangiovese, and Malbec—along with Moscatel, Criolla Grande, and Chica for the white wines. Gradually, Catena was to become one of Argentina’s leading wineries, along with Arizu, Furlotti, and Peñaflor. By the time the young Nicolás Catena entered the family business, Catena was selling the equivalent of 6.5 million 12-bottle cases of wine.

Dialing down the volume

Was it significant that his mother, Angélica, had to give birth to Nicolás Catena in their house in the vineyard, while his brother and sisters were born in hospital? As a child, Catena lived in this house with his brother Jorge and sisters Silvia and Maria Angélica. Expected to work from an early age, he divided his time between school, reading, and tending the farm animals. He’d be up at dawn to bring in the horses and cows before heading off for school, then take the horses back to graze after school. Before he was packed off to the Licéo Militárat the age of 12, the young farm lad was carrying out jobs in the winery, such as entering open-top concrete tanks at harvest and removing the pomace with a shovel, and he learned how to macerate the grapes using pumping over and irrigating the cap. Domingo was so delighted with his son’s application that he rewarded him with specially adapted equipment.

At the Licéo Militár, Nicolás Catena discovered his aptitude for mathematics. He finished secondary school in 1955, the year in which Péron was ousted by the military—“a good day for Argentina and the world,” according to Winston Churchill. He started at the National University of Cuyo at the precocious age of 16, graduating with a degree in economic theory in 1962. Accepted to study mathematical economics at the University of Chicago on a PhD program, his life changed overnight when his mother and grandfather were killed in a road accident. Deciding that he had no alternative but to sacrifice his budding academic career and work instead for the family company, he entered the business in 1963, and a month later he was running it.

The Argentinian wine industry was on the cusp of an unprecedented boom in vino común. Not only did the vineyard area increase to 815,500 acres (330,000ha) in a decade, but the short-sighted uprooting of much old-vine Malbec and Semillon in favor of higher-cropping varieties such as Criolla led to the production of more grapes per acre than any other wine-producing country. Consumption soared. Under daily wine-drinking guidelines laid down by the Argentine Wine Association, workers were encouraged to drink between 1.5 and 3 US pints (0.75 and 1.5 liters), other adults at least 1 pint (0.5 liter) at each meal, and children up to one glass a day. As Laura Catena points out in Vino Argentino, “[At its 1973 peak] at 100 liters [26 US gallons] per capita, Buenos Aires was behind only Paris and Rome in wine consumption.”

The number and scope of the innovations made in those early years set the stage for the subsequent dramatic changes with which Nicolás Catena is more commonly associated. First, he added the Crespi and Esmeralda brands to sell more wine in the big cities of Cordoba and Buenos Aires. Next, he changed production techniques, enlisting a consultant, Professor Juan Goméz, to help soften the blends. Taking two leaves out of Coca-Cola’s book, he established a new sales force to sell direct to retailers and used TV to market wine as a natural, healthy product to be consumed at the family dinner table. For thus promoting happiness and social responsibility in family life, he was awarded the coveted Santa Clara de Asis Prize by the Catholic Church.

During a stint on a masters program in applied economics at Columbia University in New York in 1972, Nicolás Catena was regularly invited out for lunch by the Argentinian consul, and it was on these occasions that he developed a taste for Cabernet Sauvignon and the first growths of Bordeaux. Determined to try to find a way of making great wine on his return to Argentina, he took on the talented viticulturist Pedro Marchevsky and, soon after, hired the winemaker José Galante, then only 24, to start working on improvements in the vineyard and winery. Yet, as Ian Mount writes in his book The Vineyard at the End of the World, “Catena’s desire to make wine in the traditional style but better was like aspiring to be the world’s tallest midget.”

Throughout the political, social, and economic turbulence of the late 1970s and early 1980s, Catena continued to flourish. Unlike many, the company survived the Andes Bank scam conceived by the flamboyant Héctor Greco and the subsequent wine crisis. When the bubble burst on Greco’s arrest and imprisonment, thousands of acres of vineyards had to be pulled out and many wineries sold off or closed, with the loss of thousands of jobs. Nicolás Catena, however, outsmarted the megalomaniac wheeler-dealer by cutting a cunning $129-million deal that allowed him to hang onto the Catena winery and ultimately take back control of most of his other bodegas. For Catena, who had already been thinking about the changes required to get out of the rut of mass consumption of plonk, the crisis was a wake-up call. It was time to forge ahead with his long-term ambition of adding value through quality and, ultimately, the réconversion of the wine industry itself.

A new dawn

Although convinced he could make a great Argentinian wine by the time he left Argentina to take up an academic post in 1981 at the Department of Agricultural Economics at the University of California in Berkeley, Nicolás Catena was still resigned to its second-class status compared to the French greats. But with baby daughter Adrianna in a backpack, visits by Nicolás and his wife Elena to Robert Mondavi’s Oakville winery in Napa Valley in 1982 galvanized his ambitions. Tasting delicious wines with bright fresh fruit, flavor, and concentration was a revelation. It struck Nicolás forcefully that it might indeed be possible for Argentina, too, to make world-class wine outside France.

This insight came soon after the seminal 1976 Judgment of Paris and the Opus One Old World/New World joint venture conceived between Mondavi and Baron Philippe de Rothschild in 1979. The inquisitive student absorbed everything he was told and experienced, returning to Argentina convinced that he could make a great wine. It became an obsession. He knew that everything in the winery and the vineyard would have to change, but in his view such a transformation could only be achieved with help from outside. He introduced his first international consultant in Guy Ruhland from California, who carried out benchmark tastings with competitors, soon to be followed by the influential figure of Paul Hobbs. Around the same time, Catena bought land in Agrelo for planting Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon, as well as the Angélica Vineyard in Lunlunta which was already planted to Malbec.

Paul Hobbs, a winemaker at Simi at the time, was on a trip to Chile when he was lured to Argentina in 1988 by his fellow alumnus from UC Davis, Nicolás Catena’s brother Jorge. Horrified by the old-fashioned winery, Hobbs was nonetheless impressed by the vineyards and persuaded by Nicolás Catena to make a barrel-fermented Chardonnay. Without the proper know-how at the winery, his first effort, in 1990, was left to oxidize, much to both his and Catena’s fury. Investments were made in a pneumatic bladder press, a destemmer, and oak barrels, and with proper oversight from Hobbs, the 1991 Chardonnay and 1990 Cabernet Sauvignon were launched on the US market. The most expensive Argentinian wine at the time was Fond de Cave, selling for $4 a bottle, but Catena’s US importer, Alfredo Bartholomaus, was so impressed with the “new” wines that he went along with the mathematical economist’s bold plan to launch the Chardonnay at the ambitious retail price of $13 and a Cabernet Sauvignon at $15. Setting the price bar so high in the marketplace was risky, but because even at these price points the wines overdelivered, the gambit worked.

Hobbs went on to establish his own Mendoza winery, Viña Cobos, and in due course the Bordelais flying winemaker Jacques Lurton did the same. At first, Lurton made a Chenin Blanc and Merlot at the Esmeralda winery for Tesco, wines praised by Kathryn McWhirter as “wonderful value” in The Independent on Sunday in 1992. When Lurton initiated his J&F Lurton range, Catena took him on to work at the newly purchased Escorihuela winery, which was bringing in higher-quality grapes from Chacras, Vistalba, Luján, Medrano, and Uco Valley. Before moving to his own winery at Vista Flores in Uco Valley in 1996, Lurton made his first high-quality red, the 1995 Gran Lurton Cabernet Sauvignon. The Bordeaux-centric Catena saw Lurton as, like himself, basically a Cabernet man. But when one evening over dinner he served the 1990 Cabernet Sauvignon, Lurton damned it with faint praise as a hot-region Cabernet that reminded him of the Languedoc. Catena was shell-shocked, but realizing that Lurton was spot-on, this insight marked the beginning of a quest for cooler sites with greater variation in day- and nighttime temperatures.

Research into cooler climates pointed to the Uco Valley, where vineyards at altitudes of nearly 4,000ft (1,200m) in Tupungato were already showing the quality of Chardonnay there. The problem was that Uco was not only relatively inaccessible; it also didn’t have the traditional irrigation systems of Luján, and late frosts were a danger, too. Weighing the risks against the investment potential, Catena made the decisive shift to Uco Valley, planting the Domingo Vineyard in 1992 at 3,675ft (1,120m) in Villa Bastias, soon followed by the purchase, and first planting in 1993, of the 270-acre (110ha) Adrianna Vineyard at 4,790ft (1,460m) in Gualtallary and, in 1996, the Nicasia Vineyard at 3,592ft (1,095m) in Altamira. It was an expensive experiment but one that led to the all-important conclusion that the combination of low temperatures, high sunlight intensity, and poor Andean soils constituted a new and unique concept of terroir.

The Malbec conundrum

In her Claridge’s Hotel, London presentation earlier this year of the Catena wines to be launched on the Place de Bordeaux, Laura Catena commented that until her father started the export push at the beginning of the 1990s, there were no Malbecs on the international stage to speak of. “Malbec was an afterthought,” said Laura. “But why did the French get rid of Malbec if it was so good?” She cited the 1879 Encyclopedia Britannica, which had stated that Malbec was the dominant variety in the Médoc, but it was low-yielding and there had also been a little ice age in Europe, and Malbec was prone to millerandage. Indeed, in his translation of Charles Higounet’s Château Latour, the late Financial Times wine correspondent Edmund Penning-Rowsell points out that “Lamothe [Latour’s director from 1807 to 1835] was the first to specify two noble grape varieties: the Malbec and the Cabernet.”

The problem for Catena was that while Cabernet Sauvignon’s image was well established by its dominant presence in the Bordeaux first growths, Malbec not only had no such reputation, but as the grape of Cahors, it was a prophet without profit both in its own land and, equally, in Argentina. While his father Domingo had seen the potential for Malbec as a component of the tipificador’s vino fino blends, Nicolás Catena had no such faith in it, associating it, rather, with the old-fashioned oxidized wines he had set his mind against. However, because of the sense of duty he felt toward his father—who tried to persuade him shortly before his death that Malbec was Argentina’s best grape—Nicolás Catena made the decision to give Malbec a try.

On visiting the 195-acre (79ha) Angélica vineyard in Lunlunta, Paul Hobbs had already seen the potential for good wine from the deep-rooted old Malbec vines grown with flood irrigation. He initiated an undercover project with Pedro Marchevsky and winemaker José Galante. Aging the wine in Seguin Moreau oak barrels, Hobbs showed it to some visiting journalists, one of whom, Tom Stockley, sang its and Malbec’s praises in a Seattle Times article titled “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina.” This was the genesis of Alamos Ridge, which was to become such a hit on the American market, as Alamos, for its naturally bright, soft, New World style. Yet while Nicolás was encouraged by the results, he wasn’t yet ready to launch a Malbec under the Catena brand name.

After being taken on by Nicolás Catena to see what could be done with the Sangiovese grape so prevalent in Argentina’s vineyards, Tuscany’s Attilio Pagli concluded that Mendoza’s Sangiovese bore little relation to the Tuscan variety he knew and loved. Attracted to Malbec, however, for its fragrant aromatics, intense flavor and round, sweet tannins, he turned his hand to the variety with Catena’s reluctant agreement. Indeed, he became so enamored that in due course he started his own winery, Altos Las Hormigas, with the Italian uber-consultant Alberto Antonini and Antonio Morescalchi. Using his stock-in-trade saignée of the grapes to concentrate the fruit, in 1994 Pagli made the first Malbec that Nicolás Catena felt confident enough to launch on export markets, but only after it received the thumbs-up from Laura Catena and Pedro Marchevsky. “Elegant yet rich and flavorful, this medium-bodied, supple, velvety-textured wine exhibits just what heights Malbec can achieve in Argentina,” Robert Parker wrote.

Working with her father from 1995, Laura Catena had already concluded that Malbec was capable of making something profound, and further progress was made with the 1995 Malbec, but the 1996 was the turning point. Made in a cool year from 2 acres (0.8ha) of lot 18 in the Angélica vineyard, with a heavy saignée and aged for 18 months in French oak, it was rewarded with the name Imperial, reserved for the best wine of the vintage. Comparing it with the 1997 Weinert, which he had previously mentioned as Argentina’s best Malbec, Robert Parker gushed with a sensational 91–94 points. According to Pedro Marchevsky, “The 1996 Imperial Malbec was the wine that first really made Nicolás Catena sit up and finally take note of the full potential of Malbec.” After the 1996 Catena Alta Malbec, Catena said, “When we decided that Malbec was going to be something big in the company, then obviously we started to do two things: planting Malbec at higher altitudes and microclimate blending.”

Meanwhile, Malbec was to be put through its paces with a major clonal-selection project based on the best material from the Angélica vineyard. After a pre-selection process by Pedro Marchevsky and Catena’s new viticulturist Alejandro Sejanovich, 135 cuttings were propagated from the original vines and planted out in the 3,000ft (930m) La Pirámide vineyard in the Agrelo district of Luján de Cuyo. After micro-vinifications of small batches, five clones were selected based on their vegetative (vigor and root growth), reproductive (bud fertility, berry and cluster size, fruit set and millerandage), and enological behavior, then planted out in the Adrianna and Nicasia vineyards at Gualtallary and Altamira respectively.

Into the 21st century

Catena, meanwhile, had long been thinking about building a new winery designed not just to make the highest-quality wine but also as a way of giving visual substance to the growing reputation of the brand. On a visit to Guatemala, Ernesto Catena had been struck by the hidden meanings in the pyramids of the Indian tribes. He persuaded his father that Tikal—the pre-Columbian temple that rises to 155ft (47m) in the abandoned Mayan city of the same name—would fittingly symbolize both a hinterland and a sangria, a mix of the bloods of different races. This architecture, embodying the melting pot of his own cultural background and his quest for a self-evident New World identity, resonated with Nicolás Catena. So it was that on April 1, 2001, Tikal was inaugurated, a Mayan-meets-Space Odyssey winery as bold in conception as Catena was introverted. By this time, guest of honor Eric, Baron de Rothschild, had just entered into the CARO partnership with Nicolás Catena, channeling Mondavi/Mouton’s Opus One.

Shortly after the opening of Tikal, the 1997 Nicolás Catena Zapata was released at $80. Following the success of the 1996 Catena Malbec, Nicolás Catena had decided, with characteristic caution, that the new flagship red, a Nicolás Catena Zapata, should be a Cabernet Sauvignon rather than a Malbec. The 1997 vintage was so good that Laura convinced her father, who was nervous about whether or not to do the tasting, that the 1997 Nicolás Catena Zapata was the one to put up for a series of nine international blind tastings in 2001. Taking place in America and Europe, where it was compared blind to 1997 Château Latour, Haut-Brion, Solaia, Caymus, and Opus One, it came first in six of eight American cities. In London, the day before 9/11, it made its biggest splash when it was chosen as the top wine by discerning palates including Jancis Robinson MW, Anthony Hanson MW, and Oz Clarke.

This was as much a victory for Nicolás Catena as a personal triumph for Laura, who, since working with her father in 1995, had steadfastly insisted on the value of taking a risk that her father had initially been reluctant to take. As a Harvard University graduate and a medical doctor, Laura has an academic prowess and science background that propelled her toward organizing Catena’s research experiments aimed at a greater understanding of the terroir. That same year, she became director of research and development for the winery (later to become the Catena Institute of Wine in 2013), with a view to researching high-altitude Malbec and Malbec clonal selection. The research showed that sunlight intensity helped in the polymerization of tannins, bringing concentration and smoothness, as well as increasing the amount of floral, violet-like aromas. From this new theory of the effect of altitude and sunlight intensity, a new approach to the blending of microclimates evolved.

The opening of Tikal and this new approach happily coincided with the head-hunting from the research body INTA, the Instituto Nacional de Tecnologia y Agricultura, of the talented winemaker Alejandro Vigil, who joined chief winemaker José Galante in 2002. With hundreds of microvinifications of wines based on different yields, types of fermentation, drip-irrigation systems, and vine age, winemaker and viticulturist joined hands in the in-depth exploration of the vineyard. From the 2004 vintage, Vigil was entrusted with making Catena’s top wines, including a new top Malbec, the 2004 Malbec Argentino, a synthesis of more than 300 cuvées of the best plots from the Adrianna and Nicasia vineyards, harvested at different times and initially co-fermented with Viognier. Realizing that Malbec needed respect as a very different animal from Cabernet, Vigil, promoted to the top job in 2007, started to change the Malbec, picking earlier at higher altitude, using wild yeasts and, among other techniques closer to Pinot Noir than Cabernet, punching down, with whole-bunch fermentation and large oak barrels.

One of the major focal points of the research was Adrianna Vineyard, an analysis of whose Chardonnay showed that differences in the soils had a significant effect on the wine. Research showed that Adrianna was an alluvial cone with three distinct geological origins—alluvial, aolic, and colluvial—and so distinct wines, with relative vigor a factor, could be made from the 11 different lots into which the vineyard was divided. Under the supervision of Catena’s new viticulturist Luis Reginato, Vigil made two Chardonnays—White Stones and White Bones—so named by Laura Catena to reflect the different physical soil compositions of the two lots, both at 4,750ft (1,450m). These are arguably Argentina’s finest Chardonnays, both with a tautness and mineral character absent in all but a very few Argentinian Chardonnays.

At the same time, Luis Reginato was charged with sourcing three Malbec wines from Adrianna based on the differing microbiology of the vineyard’s soils. Mundus Bacillus Terrae, from the same soils as the White Bones, at the highest altitude, is so called because of its population of microorganisms interacting with the roots and the enhancement of Malbec’s ability to absorb nutrients. Fortuna Terrae, initially called The Good Spider, comes from deep, sandy loam alluvial soils over calcareous rock with more insects, hence the original name. And finally, River Stones comes from similar soils to the White Stones, a red whose violety lift, twist of pepper, and rounded fruit purity is not a million miles from Côte-Rôtie. After 28 soil pits per acre (70 per hectare) were dug, Laura concluded that some 30ha (74 acres) of Adrianna’s vineyard were “grand vin” quality, with a unique taste and minerality.

Along with the flagship Nicolás Catena Zapata, it was the Mundus Bacillus Terrae that Laura Catena chose to launch onto the Place de Bordeaux this year, hence the tasting at Claridge’s of three vintages of Nicolás Catena Zapata (the 2005, 2010, and 2015) and two vintages of Mundus Bacillus Terrae (2011 and 2015). Why this innovation? “We realized if we wanted to be considered the best in the world, the proof that we are achieving this is the consumer, the people who buy ageworthy wines with a reputation to cellar and drink later,” said Laura, adding, with characteristic humor, “We want our wines to age. I always talk about our 100-year plan, which is convenient because I won’t be around to see whether we were right or not.” The 100-year plan is no joke but, rather, the long-term ambition of Catena’s multigenerational success story.

Laura’s respect for her father’s work is equally tempered with good humor. “Nicolás tortures us daily, but in a good way. Every time we feel happy about something, he asks a question that makes us doubt ourselves.” With her father’s economist mind, protean energy, and perfectionism, and her mother’s intuition, humor, and outgoing personality, Laura runs one of Mendoza’s top wineries while also managing to be doctor, mother, wife, and author (of Vino Argentino), and living in San Francisco. Standing in front of trade and press in her trademark raffish beret, it was abundantly clear that Laura is a woman who’s more than capable of holding her own while sharing in, and building on, her father’s mission and vision. “I want Catena to be in every single cellar, and I hope I don’t die before that, so please help me die happy.”