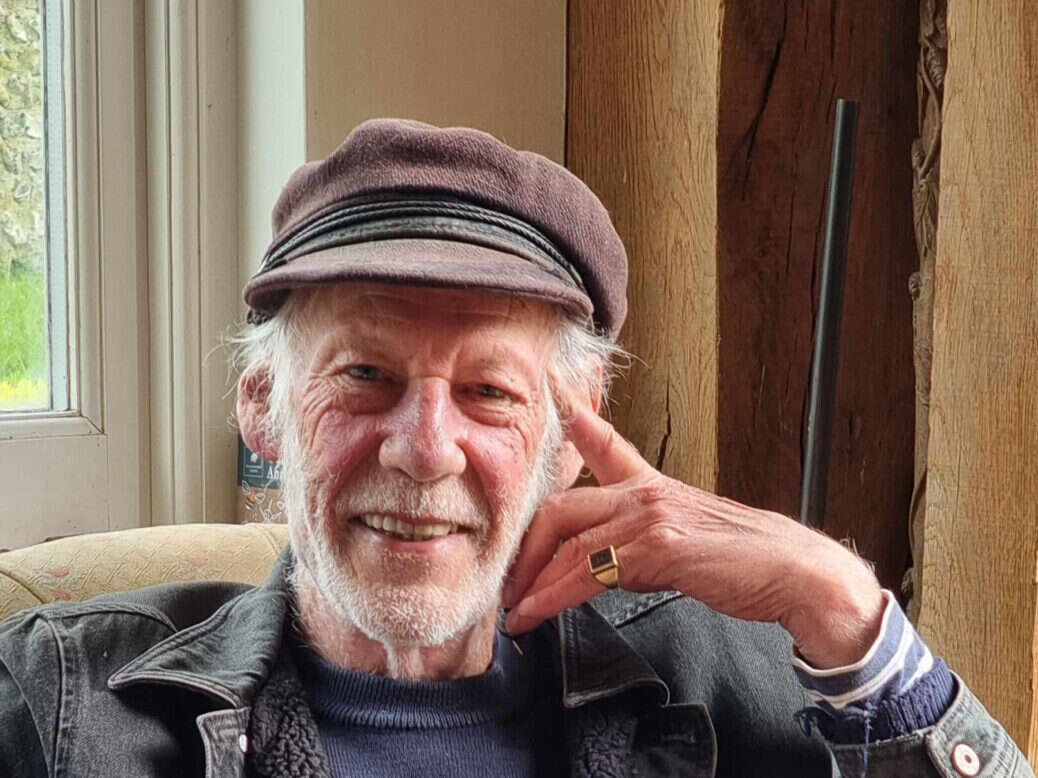

Margaret Rand attempts to keep up with the tangents and diversions as she follows the endlessly fascinating life story of Peter Hall, the English wine pioneer at his home on his secluded farm, Breaky Bottom, near Lewes, East Sussex.

An interview with Peter Hall is to a résumé what Homer’s Odyssey is to Google Maps. It wanders; it dives off at tangents and never comes back; and unlike Ulysses, it never actually arrives at the destination you expect. But gosh, it’s a lot of fun.

To give you a flavor, this is what happened when I asked him how he learned to make wine: “From a book. I did, actually.”

Then he flipped to Andrew Jefford (an old friend) and discussions of terroir—“If you were in Brixton and had a little garden and grew vines, there would be nowhere else in the world like that”—and then onto delivering the eulogy for his aunt at her funeral: “I said I wouldn’t do a traditional eulogy about how wonderful she was, and I turned to the coffin and said I’m going to talk about my late aunt Janie, and I talked about— I was born and bred a Catholic, but as a young teenager I got further and further away. I’m an agnostic, and there’s a cigarette paper between that and atheism, but I still say I don’t know. I’m not trying to buy myself a ticket just in case…

“The first wine I ever made here, in a barrel, was still wine. My wine chemist—a shit-hot wine chemist, Maria Russell—knew Peter Reynier, who gave a wonderful crit of this wine: He said it had a fabulous nose. Then it falls down because the style of that nose is never respected; the graph is wonky. The shape of the wine is important.”

I ask the question again. “I’ll review this while I open the next wine. I told my son Jon, who is a sculptor, I could teach him to make wine in 20 minutes. Rubbish, of course. But a few 20-minutes a week…”

Who taught you? “The good Lord above.” This in an Irish accent. “I don’t know. Look, this is Cuvée Michelle Moreau.”

And we’ll come to her later.

It’s an exhilarating ride, bouncing between people and places, music and ideas, 50 years ago and today. What emerges—often between the lines, since straight answers are not really Hall’s thing—is a man of immense stubbornness and courage, ultimately elusive, and profoundly and joyfully a world away from everything you could possibly describe as “modern.” Breaky Bottom itself is barely accessible and self-contained, full of books and music. And it is his creation.

Early lessons in terroir and tenacity

But to begin, as Dylan Thomas said, at the beginning. Hall was born was in 1943, on April 21, which is the same day as the Queen’s birthday. “Every year there’d be a 21-gun salute in Kensington Gardens, and I thought, How nice.

“My Irish granny was from the Lake District, but her husband was killed at Gallipoli, and at 31 she was swept up by my step-grandfather and moved to Gloucestershire, to a house that had 26 rooms, and I was born there.”

It also had a big old-fashioned mixed farm attached to it, which any amateur psychologist worth their salt would say had an effect on him.

“My brother Remy was born in 1941.” He also has a younger brother, Patrick. “Mother was French, an amazing woman. Dear Mother. The only language when Remy and I were born was French.”

His father worked for Marconi but wrote all night long—short stories, for which there was a good market then. Her father was from Normandy, and until the 1930s he had had a restaurant in Soho, where the clientele included opera stars from Covent Garden, VIPs, and the odd prime minister; and he (the grandfather) was who introduced Hall to the wines of France.

When he retired, he went to the Midi, and during holidays there, “when my parents went off to Antibes to get pâté for lunch, he would sit us down under a big old olive tree in the shade, with a bottle of Morey-St-Denis, and say, ‘Respect the label.’ He would describe [the site], saying it faces east or southeast, it catches the morning sun, if you planted it farther up it would be too cool, and farther down it would be too warm; respect the label, the maker, the year.”

His other grandparents were English, Irish, and Italian. He doesn’t speak Italian, he says, but he can gesticulate in Italian. He speaks to Toto the cat in “invented Persian” (Purrsian?), and he’ll slip into a French accent, or Geordie, or Italian, or All-Purpose Rustic whenever he feels like it. Anyway, his Irish granny took one look at the newborn in the cottage hospital in Chipping Sodbury “and said, ‘Chiang Kai-Shek.’”

Later they moved to Sussex, to a mill with trout in the stream, and at the age of 12 he fell in love with Schubert, and on stays in London he and Remy could walk to concerts—“now people would be reluctant to let 12-year-olds wander in London.” (“When I became 31,” he adds later, “I said to Franz Peter Schubert, I will expand and put you on one side, but in the last 15 or 20 years I’ve come back to him.”)

He developed a crush on the au pair, Francine, who in his mind was his first girlfriend—and she crops up later. He fell in love with birds and finds it amazing how they communicate. “One day, there will be a Pocket Oxford Dictionary of Crowspeak.”

He decided to study agriculture at Newcastle University. (He pronounces Newcastle with an appropriately short “a.”) “I loved the Geordie accent and the Northumbrian countryside,” and he has happy memories of “the medics, who drank like fishes and still do.”

Post-Newcastle (short “a”), he had to decide what to do and thought he should probably get practical experience on a farm. A schoolfriend, training to be a solicitor, knew the man who ran North Ease Farm near Lewes in Sussex, so Hall asked this man if he could work for him on the farm for a year.

“I lived in a room in Brighton over a bar, with umpteen tenants queuing for the loo. I would get up at 4, have breakfast, make my sandwiches, wrap them in greaseproof paper, and take two buses to get to North Ease by 7.”

Soon after he started, he was told to go to Breaky Bottom on a tractor to feed the sheep. “I stopped at the top of the hill, looked down and thought, Wow. I did the sheep, then I asked him if I could live there. He was very surprised: There was no electricity, no telephone, and just a standpipe for water. It hadn’t been lived in for 50 years.”

He describes the farmer as difficult. “He was a grumpy old sod. On my 365th day, I went for orders—he was shy, and he wouldn’t look you in the eye; he’d kick a bit of flint about and give you orders. It was my last day, and I said, could I stay for another year? He said, Yes, as long as you don’t talk so much.

“It was exhausting work, but I found delight in knowing these men, the laborers, knowing about their lives and talking about things they didn’t know.” At the same time (and remember those hours), he worked in a restaurant in Lewes, for the money.

He stayed there three years, by which time his family was suggesting he should get a farm manager’s job somewhere. At that point, he met the farmer’s daughter and married her. “I didn’t know Christina then.” (Christina is the second Mrs Hall, and an artist. Between them they have six children, but none seems to be involved in Breaky Bottom.)

“The farmer sort of accepted it and said, ‘You’ll get no money, but you’re the only one I’ve ever met who likes Breaky Bottom. Do you want a tenancy?”’ So, a 13-acre (5ha) tenancy was drawn up.

In time, the farmer’s son—“who was one year older than me and a tough cookie, too”—had got financial problems, and the bank told him to sell various assets, including Breaky Bottom. He sold it to “a wheeler-dealer” over Hall’s head “because he didn’t like me,” and the wheeler-dealer promptly put Breaky Bottom up for auction.

“There were maybe 160 people at the auction. My friend Nick the solicitor from school had said, You must agree not to go over x. I didn’t have any money ready, but the night before, Francine had been on the phone to me, saying, I can lend you some money if you need.

“I was at the auction, and they were taking bids off the wall; it was classic. It wasn’t worth that much. It got to £90,000, and Nick was frowning at me. £92,000. I was bidding on, he was getting agitated, and it got to £100,000. The auctioneer lifted the gavel, and it was a lifetime before the gavel came down. I had to write a check for the £10,000 deposit.

“I knew afterward that if I’d given up at £50,000 and walked out, before I’d got out, his man would have stopped me and said, Just a minute, we can talk.”

What he had bought was 15 acres including the house and barns. Breaky Bottom now is 30 acres (12ha), and he is still a tenant of those other 15 acres. “I don’t like money,” says Hall suddenly. “I understand human nature, I do, even if people cheat.”

Risk and reward at Breaky Bottom

He first planted grapes at Breaky Bottom in 1974, which (tangent alert) was also the year when fellow winemaker Dermot Sugrue was born.

“Dear Dermot. With a bottle of Paddy, in an hour I’m as Irish as he is. Dermot once said, ‘Peter, if you were a girl I’d marry you.’ Pause. ‘If you were a wee bit younger.’”

In 1974, there were, Hall says, maybe half a dozen vineyards in England. He hadn’t really intended to grow vines until Nick Poulter, who had a vineyard on the Isle of Wight, came over and said, “This is a wonderful place to plant vines.” “So, I did.” He made still wines initially. “When I think back to my early days of still wines, I still think I’ve jumped ship.”

He can’t remember what his first row of vines was, but he thinks it was probably Seyval Blanc, because that’s what was available. “I’m a risk-taker. We were all risk-takers in those days.” Even before the first row had produced fruit, he’d planted more. “Houston, we have lift-off.” Said in the appropriate accent, of course.

Seyval Blanc was how he first made his name. Back in the 1980s, when I was editing Wine magazine, Andrew Jefford wrote a monthly diary for the magazine of a year’s visits to Breaky Bottom. During a pub lunch in the area, I ordered a bottle on the strength of what he wrote—and was utterly convinced. This was wine of depth and finesse, and it aged to a rich wineyness.

He still has about 60 percent Seyval Blanc, but in 2002 he planted some Chardonnay, and in 2004 planted 70 percent Chardonnay plus 15 percent each of Pinot Meunier and Pinot Noir. It’s the shape of the land he points to as being crucial: It’s just below wind level.

You get to Breaky Bottom by driving along a spectacularly potholed track with spectacular views toward the sea, which is only a few miles away across the South Downs. Then you suddenly dive down into a hollow, and there is Breaky Bottom. It could hardly be more sheltered.

From the wind, anyway. “It’s been flooded five times,” says Hall. There were “big fields of winter wheat, and if there are not enough roots to be grass-like… There’s no clay up there, it’s just silt, impermeable, and it just washes out.” He was flooded in 1972, 1976, 1982, 1987, and 2000.

“Last time, we lived in a caravan for two and a half years. They’d wanted to pull the house down, but it was repaired with insurance money, and he [the farmer] was told that if he flooded the Halls again, he wouldn’t be able to be covered, and he got the shits. There’s less wheat now and more sheep.

“In 2010, the farm started a corporate shoot. The birds are released on September 1, and they come down to us by September 2.” To eat the grapes, that is. “Christina documented it on film, sitting in the vineyard at dusk. It was like the Tokyo underground in the rush hour. Over six years we had an estimated loss of 30,000 bottles.” They sued, and Hall got compensation, but not much.

He made his first sparkling in “1994 or 1995” and released it at the end of the century. It was called Millennium Cuvée Mme Mercier, and it was named after his mother. “She died in 2001, and she was pretty elderly; I said, ‘Maman, une belle surprise.’ It seemed natural to do it”—plant fizz, that is.

Hall’s first sparkling was Seyval Blanc, because the vines were mature. He says that he always knew that Seyval Blanc would make good sparkling. “It’s very clean down the middle, and at full ripeness the acidity is still there.”

Rathfinny: In the Drivers’ seat

Hambledon Vineyard: Chalk show

A people thing

All his sparkling releases are named after people who have been important in his life one way or another, and these shine a light on his story, sometimes obliquely—for example, Cuvée Jack Pike, which is Seyval Blanc 2015. Jack Pike mowed the lawn when they lived in Sussex, and he and Hall became friends despite a 30-year age difference.

“He had a slight build, but he was strong as an ox and determined; he taught me how to work. He would come here to help me plant the vines. He planted the first one, and he had 10,000 holes to dig, with a spade. When he planted the first one, he said, ‘What do we do next?’ It’s a lie, but in France they say you pee into the hole. They don’t, but he did.”

Cuvée Koizumi Yakumo, Seyval Blanc 2010, is named after Hall’s great-great-uncle, who was not Japanese except perhaps in spirit; he was otherwise known as Anglo-Irish writer Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904). At the age of 40, at a time when Japan was isolated from the West, he went to Japan and lived there for 14 years.

“He loved old Japan and wrote ghost stories and myths and legends, and his work was translated back into Japanese, and the Japanese have worshipped him ever since. When I see Japanese people here, if they’re nice enough and keen enough to have one of the old bottles on allocation, I have to get low and they get even lower, and they do selfies… Every child at prep school always learns about Koizumi.”

It’s a warm, rich, deep winey wine, salty and poised. “Beautiful,” says Hall. “Well done. It’s still good.”

Cuvée Michelle Moreau 2014 is a Chardonnay/Pinot Noir/Pinot Meunier blend named after the younger sister (by some ten years) of the more famous Jeanne.

“Chris knew her in her early 20s. She died a few years ago, and they’d been really good buddies. I’ve known Chris for over 30 years, and I knew Michelle for over 30 years. She lived in Brighton. Her sister was a different person. Jeanne was dancing on tables in occupied Paris. She made great films. And such a beautiful young woman. Bring back the black-and-white films of the old days!” His all-time favorite film is Some Like It Hot. “The last line! ‘Nobody’s perfect.’”

Cuvée Reynolds Stone is 2010 and, again, a Chardonnay/Pinot Noir/Pinot Meunier blend. In 1976, Hall’s first vintage, he needed a label. Reynolds Stone was famous, accomplished, and near the end of his career. A letter-cutter and engraver, he had designed, among other things, the coat of arms on British passports, British banknotes, and memorials in Westminster Abbey to Benjamin Britten and TS Eliot. Says Hall, “I couldn’t believe he said yes.”

They became such good friends in the few years before Stone died that he asked Hall if he would like to live at his house, the Old Rectory at Litton Cheney in Dorset, because he and his wife had to move. “It had to be a firm no. But it was so touching.”

Cuvée David Pearson (2015, Chardonnay/Pinot Noir/Pinot Meunier) is, by contrast, named for the man who made the cardboard boxes for Hall’s first still wines. Hall knows his story, of course; he always knows people’s stories. Pearson was a bachelor who had been to Plumpton College; he’d been a tobacco grower and “he suffered from Hodgkin’s lymphoma or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,” and Hall’s son Jonathan called him DCBM—Dad’s Cardboard-Box Man. “I had to decide if I would call the wine DCBM.” If Hall had had a bigger vineyard, more money, more equipment, he might have been Hall’s vineyard manager.

Had Breaky Bottom been a bigger operation, perhaps he would never have staged operas in his barn. “I had to take out the tanks and put straw bales in to seat 280 people. Where the cellar is now was the stage.”

The opera company was New Sussex Opera, which is still going, and some of the singers were drawn from the chorus of Glyndebourne Festival Opera, which is conveniently close and has a formidable reputation for talent. These operas happened in the barn for three years.

The first year, “I rang the BBC, the arts department, and said I was putting on an opera, and I had vines, chickens—a mixed farm—and they took the bait. Along came two 2CVs with a soundman and a cameraman and a presenter. We pointed at each other, and we both said, ‘Newcastle.’ It was Kate Adie. She was such fun; she was a darling. The following year I went to ITV, and they came down.”

One of the operas was Peter Grimes, directed by Nicholas Hytner. But Fidelio couldn’t be staged in the barn and had to be done in Lewes, and Hall realized he couldn’t do operas anymore. He doesn’t go to the opera, either: “I’ve been a hermit for a few years now. Running a little vineyard is bloody difficult.”

Sir Harry Kroto loved music, too. His cuvée is 2013, and it’s Seyval Blanc. “Harry Kroto was a chemist. He looked at the whole universe, and he won the Nobel Prize for chemistry. He and his wife came to Lewes 25 or 30 years ago, and we became buddies. He loved red wine and never enjoyed any white, but he tasted Breaky Bottom and loved it.

“I used to bottle in halves as well, and he bought loads and would have a half with his lunch. We really clicked. He was a brilliant scientist. He had discovered a new form of carbon… carbon something. Carbon 60. Only a year before he died was it proven. Dear Harry. On his deathbed, he took his mask off and said, ‘I love you, Peter, but I still prefer your still wines.’”

Soon there will be Cuvée Sir Andrew Davis 2016. Somebody, many years ago, had just moved into one of the houses nearby; Hall bumped into him and they got chatting. “He was interested in music and kept asking questions [about the opera at Breaky Bottom], and I kept answering, and after a while I said, ‘What’s your trade?’ And then I said, ‘Shit, you’re Andrew Davis, aren’t you?’”

It was only toward the end of our talk that I asked him where he’d been to school; it was where I went, too, for my last two years, albeit (I add hastily) some years after Hall had left. The girls’ school that joined forces with his school was St Maur’s Convent; as I left and we hugged our farewells, Hall said, “That’s another St Maur’s girl I’ve kissed.” “How many is that now?” I asked. But he wouldn’t tell me that, either.