David Schildknecht reviews Beauty and the Yeast: A Philosophy of Wine, Life, and Love by Dwight Furrow.

Probe Head Publications (2020)

352 pages; $21.95 / £16.62 / €19.54

There is an unfortunate risk that the title—not to mention the sub-title—of this book will discourage the attention it deserves. Those already concerned with rigorous application of philosophical tools to matters vinous might remain unaware that this book represents just such an effort, while many enophiles, lured by the title, will be surprised to find themselves in unfamiliar, seriously philosophical territory. Dwight Furrow—an Emeritus Professor at San Diego Mesa College—goes out of his way stylistically to encourage readers from the latter camp to persist; and, without becoming excessively repetitive, offers succinct summaries of his arguments and signposts to what lies ahead that should prevent those unfamiliar with the sort of analysis that is academic philosophy’s stock in trade from losing their way. There seems a good chance that after closely reading this book, a typical enophile will be left wondering why anyone would take exception to many of its basic tenets and why so much of contemporary wine discourse seems predicated on ignoring or violating them. If so, then Furrow will have accomplished that loosening of conceptual knots into which we have tied ourselves that Wittgenstein deemed a fundamental aim of philosophy. Though along the way, he ties a few complicated, if creative knots of his own.

Worthy of love

In attempting to explain why wine is worthy of love and should be viewed both as art and “as a living organism,” Furrow arguably goes beyond what is necessary to accomplishing his essential aim of “revis[ing] our concepts of creativity, objectivity, aesthetic experience, expressiveness, and beauty to accommodate th[e] collaboration between culture and nature” that is wine. While one speaks of “wine lovers” and “Weinliebhaber,” French makes do with “amis du vin”—and it surely suffices if one can account for our fascination with, and peculiar sense of attunement to, wine. Whether or not one deems it a conceptual stretch to call wine art, a multitude of published arguments purporting to demonstrate how wine differs from art deserve the detailed rebuttals to which Furrow subjects them, in the course of which—as, indeed, in his book as a whole—wine’s claim to aesthetic assessment is reinforced and its unique aesthetic status clarified. As for “living,” what is essential to this book’s overarching account is the extent of analogies to be drawn between wine and living organisms, which in turn help explain our aforementioned fascination and attunement.

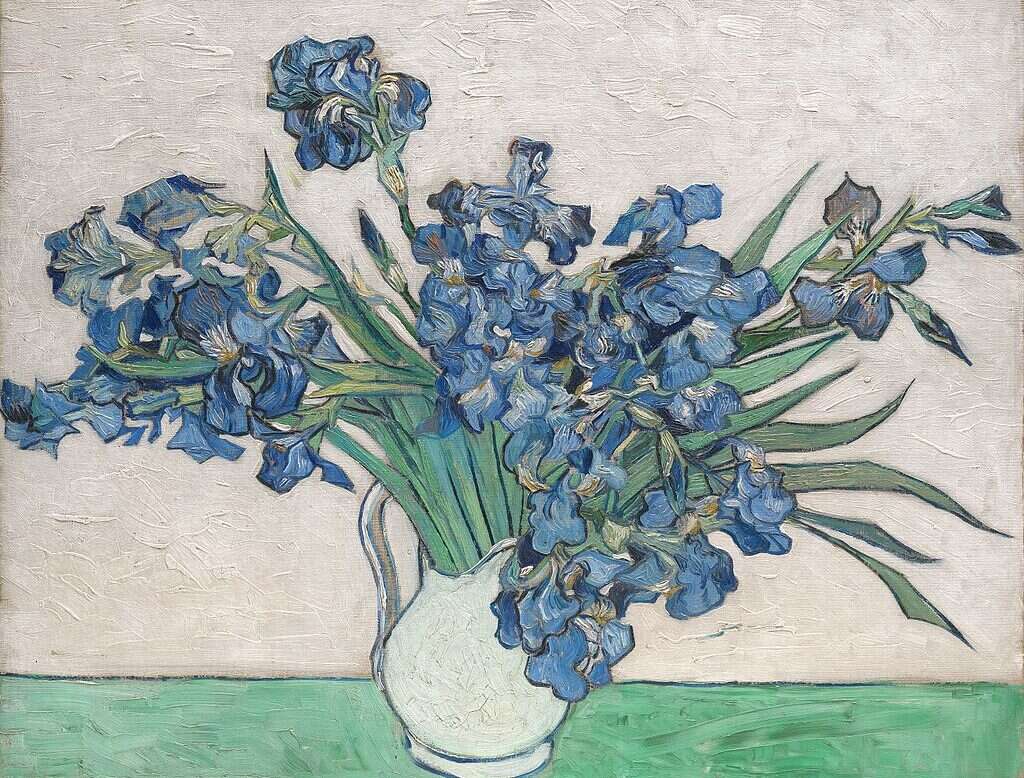

Furrow credits wine with expressing emotions as well as with being representational. He is less concerned with arguing for the latter capacity, but to the extent he does, his account prompts reservations. “A wine,” he avers, “can represent the flavor profile of a vineyard or a region.” Surely there is an equivocation at work here. The sort of representation attributed to much visual art is that of depiction. Substituting “illustration” for “depiction,” only perpetuates equivocation. A van Gogh painting can be deemed to illustrate what its title—Irises or Cypresses, say—indicates and at the same time illustrate the artist’s late, Saint-Rémy period, or illustrate how thick application of oil paint can convey a sense of motion while acquiring an independent, abstract aesthetic appeal. In the sense of serving as an illustration, a wine can exemplify an appellation, terroir, site, or vintage—and in fact, taking his cue from Nelson Goodman’s seminal theory of art, Furrow goes on to treat expressiveness as exemplification. But it is hard to conceive, nor does Furrow attempt to explain, how a wine could depict these. In any case, a vineyard—which is a physical place—isn’t something that can possess a taste profile in the relevant sense; though wines from that vineyard might, in which case a given wine might illustrate that profile.

A bit of metaphysics

Furrow comes to emotional expression by way of a discourse on “expressing vitality.” He prefaces this with what some readers may take as a warning: “To see the connection between life and wine, we must engage in a bit of metaphysics.” Others may find “bit” an understatement and what follows over-the-top:

The art of wine puts th[e] process of difference, disparity, and integration on a pedestal. It reveals and makes alluring the tensions between stability and change, degradation and maintenance, and predictability and contingency. The mediation between these demands is a persistent feature of all life. Wine makes this mediation a sensuous event. Wine is where the intersection of nature and culture becomes entangled with the tensions of eros and pathos and becomes poetry.

But Furrow quickly gets down to business by surveying theories that attempt to explain the relationship between music and emotion, then suggesting how these might be applied to wine, placing particular emphasis on psychologist Daniel Stern’s notion of music as reflecting “vitality forms” that underlie our emotions, and which arguably have their vinous counterpart in touch sensitive flow patterns and other aspects of how flavor evolves over time on one’s palate.

Furrow’s account of the sublime in wine (borrowing at once from Terry Theise and Immanuel Kant), with its contentions that sublime aesthetic vista open where words and recognition fail while “beauty fades when mysteries are solved,” might do more than merely (as his very next sentence states) “ruffle the feathers of analytical tasters.” It seems analogous to suggesting that the beauty of a musical composition fades once one has subjected it to analysis. But this is another instance where the author’s most important insights remain on solid, if less elevated ground. “[T]he marker of quality,” Furrow immediately continues, “is the ability of a wine to stimulate the imagination.” And less-than-awe-inspiring, even seemingly prosaic circumstances—such as trying to recognize the identity of an elusive scent that we’re convinced we have encountered and named before—can trigger flights of imagination that engender self-awareness as well as vinous awareness (see WFW 59, p.38). Were we to succeed in re-identifying that scent, a certain sort of mystery would indeed have been solved; but it’s hard to conceive that the wine’s beauty (if in fact we found it beautiful as well as intriguing) would thereby fade, much less that the insights and pleasure derived from having exercised our imagination and explored our memory in the search could somehow be taken back.

The essence of fine wine

However rarified the atmosphere into which Furrow’s occasional metaphorical or metaphysical flights take readers, or occasionally convoluted his conceptual cross-stitching, Beauty and the Yeast is largely tightly argued, and it’s refreshing how many prevalent pitfalls its author avoids. He distinguishes between commercial and artisanal wine, but with carefully considered criteria such as are generally missing when that dichotomy is invoked. He writes of subjectivity and objectivity in wine evaluation, but places that overworked polarity in a properly nuanced philosophical context that includes detailed critical expositions of the relevant recent literature. Furrow impressively dissects the role of the wine critic, and in lieu of the typically simplistic and sloganeering treatment offers an insightful discussion of Robert Parker’s approach to wine criticism—under the social-theoretical rubric of “deterritorialization”—and its relevance to creeping homogenization. Whether or not a reader is persuaded that “the central issue in wine aesthetics [is] the problem of homogeneity,” few will argue with the sentence that follows: “The wine world thrives on variation.” And variation, together with its corollaries of contingency and creativity, are perceived by Furrow as the essence of fine wine, and as accompanying every stage of its generation as well as its appreciation.

Furrow candidly admits to leaning heavily on the intriguing theories and model of wine quality propounded by enological consultant Clark Smith, which narrows the book’s perspective. Occasionally, some misinformation is imparted or naivety betrayed, especially concerning “Old World” wines. Furrow would have readers believe that, in contrast with the homogenizing effects of commercialization in the US, “France and Germany […] for the most part, continue to target consumers with the experience (and disposable income) to appreciate distinctive terroirs.” If only! Furrow’s faith in site-influence as a guarantor of distinctiveness itself borders on naivety. And while an excellent case can be made—or an account of vinous aesthetics might plausibly stipulate—that wines of distinction are perforce distinctive, the converse constitutes a dubious contention with which Furrow flirts.

Aesthetically virtuous

A more diversified account of what makes a wine aesthetically virtuous and the approbations we bestow on wines would have been useful, as well as appropriate to the complex “mesh of dispositions”—taster’s as well as wine’s—that Furrow treats as underlying our vinous experience. In common with Douglas Burnham and Ole Martin Skilleås (in their Aesthetics of Wine, see WFW 39, pp.28–30), Furrow treats an extremely small number of attributes—notably complexity and elegance—as quintessential aesthetic concepts, i.e. markers of aesthetic appraisal, yet fails to justify that narrowness or to analyze critically those two extremely broad and elusive notions. The problematic breadth and elusiveness of “elegant” surfaces when Furrow’s “dispositional realist” theory of wine appreciation leads him to contend that “the quality of elegance is […] a disposition of [a] wine, a capacity of the wine to cause perceptions of elegance in properly situated observers.” Surely the amorphousness and huge fungibility of elegance, like beauty itself, reinforces an impression that it is in the eye or olfactors and palate of the beholder. “The next time someone tells you beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” writes Furrow, “just point out that it depends on whether the beholder has an eye for beauty.” But a quip cannot substitute for an explanation of how to assess whether a beholder is properly situated without begging the question at issue. (Even the notion of optimal conditions as applied to color attributes is not unproblematic.)

It’s hard to imagine a subscriber to The World of Fine Wine failing to benefit from reading Beauty and the Yeast, whether inspired or provoked by its author’s more metaphysical musings. This well-indexed book is sparingly but excellently footnoted at the end of each chapter, which will prove especially useful for those wishing to pursue the relevant philosophical literature. In intent, at least, a 31-page appendix “supplies the linkages needed to make practical use of [the book’s] theoretical claims” when describing wines. Under the heading “Inspirations,” Furrow offers an account of wines—many from far-flung and internationally unfamiliar North American estates—that prompted or that illustrate the views expressed in each just-concluded chapter. Furrow regularly reminds readers that his arguments and analyses simultaneously chart a personal journey, and his book is that much more compelling for its heartfelt confessions of vinous discovery, love, and wonder.

Beauty and the Yeast: A Philosophy of Wine, Life, and Love by Dwight Furrow is published by Probe Head Publications (2020)

352 pages; $21.95 / £16.62 / €19.54