The late 1980s; a tired, fume-laden street in London’s Notting Hill; a basement room underneath a wine bar. Fifty assorted Beaujolais wines. Here are some sheets of paper and a pen—off you go. This, I remember, was my first professional wine-tasting engagement, for the long-defunct Wine magazine. It was traumatic. The wines (many from co-ops and négociants) seemed largely undifferentiated and largely uninteresting: What was there to say? I slogged on from bottle to bottle, like a monk plodding up and down an MC Escher staircase. Escape from the endless circularity somehow came. I slunk home, ashamed of my terrible debut.

With hindsight, perhaps “terrible” is an exaggeration; much Beaujolais in the late 1980s (crus included) was light, homogenous, forgettable. And I did, after all, know exactly what this wine could be.

In the mid-1970s, seated at the lunch table of a flamboyant (later disgraced) priest, a Beaujolais-Villages had opened my nose and my mouth to the phenomenon of irresistible drinkability—wine so gorgeously inviting that you cannot stop until it’s all gone. This changed my world. It’s why, circuitously, I’m here today. What higher wine ideal can there be? Even the grandest, gravest wines must shed their masks and cloaks to arrive, at last, at that place of carnival where everything comes off, as nose, lip, tongue, and throat dance the fermented grape juice off to oblivion. It may happen sooner, it may happen later, but any wine that fails to ignite that desire, that delight, and that final abandon has itself, somehow, failed.

Drinking Beaujolais with Rabelais

Among less expensive wines, of course, we live with such failure all the time. “It didn’t cost much; what can you expect?” This bottle—and many of its contemporary Beaujolais peers—protests: You don’t have to live with failure. For the price of a couple of duck breasts, you can open wine of explosive, joyous riot.

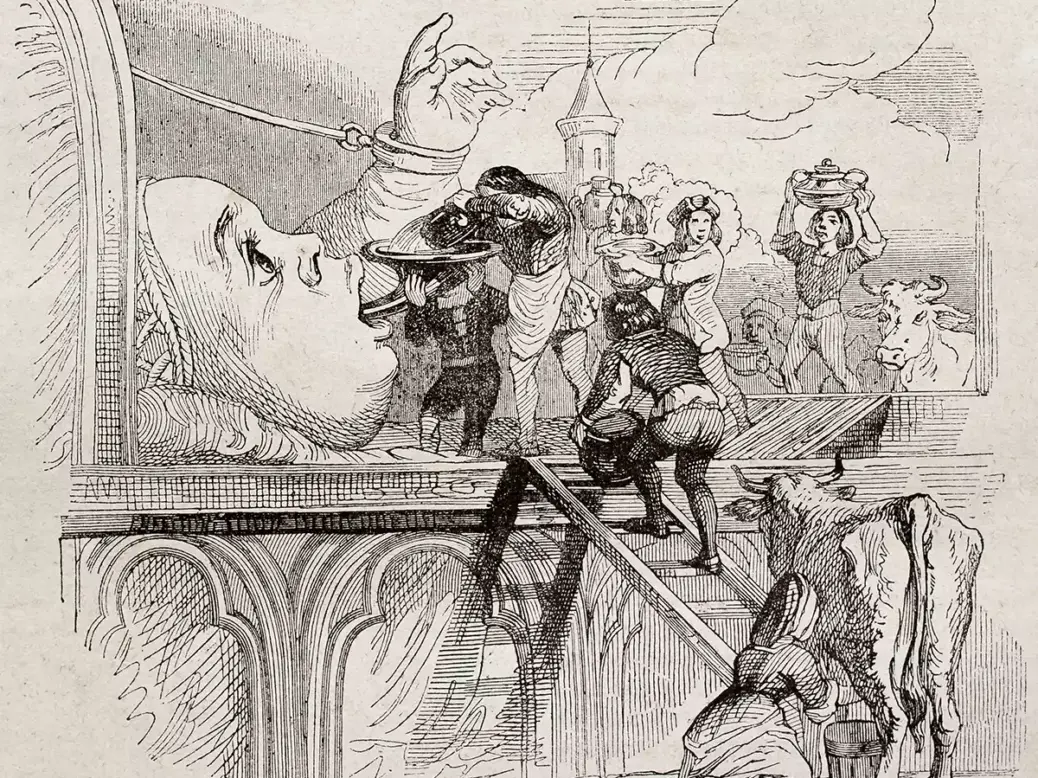

The bottle of Brouilly came to me from M Chavy via a friend. It’s sans sulfite, without added sulfur dioxide—wine “in its original version,” according to M Chavy’s back label, when “the terroir is sublime, the color more intense, the aromas exalting, and the taste gourmand, round and silky.” These words on a label can sometimes hoot a warning, but here they proved true. The wine was deep purple-red and opaque. Aromas calved from the glass: powerfully fruit-laden, of course, but with citrus-peel perfumes, too—and spotless, wholly undeviant. When you tumble into red wines of carnival and riot like this, Rabelais and his Gargantua motto come to mind: “Live joyfully!”1 Monk, doctor, theological scholar, humanist, curator of obscenities, and compiler of colossally irreverent, wine-sodden word-riffs written almost 500 years ago, Rabelais could, I felt, have been sniffing Chavy’s Brouilly with me. “Ah, the bouquet of wine: how much more smiling, whiling, beguiling it is, much more paradisiacal and delightful than that of oil!”2 Well, indeed. This was the sort of scent after which sipping becomes obligatory. “I moisten. I humidify. I drink lest I die.”3

Actually I felt M Chavy’s “gourmand, round and silky” undersold the palate, which to my mouth seemed deep, dark, shocking, and deliciously grippy, though the grippiness was so bound up in the storm of fruit that you might not perceive it as such. The fruits were sweet but juicy, not sucrous; those citrus-peel perfumes were amplified on the palate into the richly bitter flavors that sweet fruit craves. I’ve sometimes thought that, as our climate roars on toward apocalypse, Beaujolais’s acid-soiled hills would be better planted with Syrah than with Gamay—but here the Gamay had almost Syrah-like force and energy rather than being some kind of Pinot manqué. As a means of expression of place, in fact, Gamay is almost uniquely protean; the grower can lead it in so many directions. “[T]ravailler la vigne et le vin,” wrote M Chavy to me, by hand, in a note that arrived with the bottle, “c’est composer avec la nature, une quête vers un idéal, observer, comprendre, tenter, apprendre” (“To work the vine and wine is to compose with nature, a quest toward an ideal, to observe, to understand, to try, to learn”). There speaks the grower—but there speaks Beaujolais itself, France’s Janus region, gazing both north to the cool hills and south to the warm stonefields, its Roman curls ruffled, too, by the winds that come off the daunting mountains to the east and the retired volcanoes to the west. Chill winds, chilling the wine. “[I]f possible drink some cool wine.”4 Of course.

It’s a young wine, barely a year old, so a part of the pleasure is the memory of the tumult of ferment. It’s the ferment, as much as the grower, that makes the wine; grape juice, after all, is disappointment. The aging of wine is a forgetting of ferment. Sometimes, perhaps, this is wise—but here’s a wine that loves remembering its ferment, always both carnival and riot. The purity with which this is done (not always easy; much can go wrong) is yet another measure of the grower’s skill. M Chavy steered it down the line.

Now the bottle is drained. This Brouilly was, as Rabelais said of the Gali, his countrymen, “naturally joyful, candid, gracious, and well loved.”5 A wine other than a fine Beaujolais might not have been—or at least not to the same extent. Better still, I feel “an everlasting asperging of my dry and gristly innards,” which is at least one of the roles good wine must accomplish.6 Everlasting? Well, I know where to go next time. Merci, M Chavy.

NOTES

1. François Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, translated by MA Screech (Penguin Books, London; 2006), p.203.

2. Ibid, p.208.

3. Ibid, p.220.

4. Ibid, p.210.

5. Ibid, p.239.

6. Ibid, p.221.