It was the eighth day of the nominal shutdown of the US federal government, and political pundits everywhere couldn’t help but remark on what the founding fathers would do if they were alive to see this mess. Almost certainly they would have been gathered in the back room of Plume, the restaurant at the Jefferson Hotel in Washington, DC, lured by the heady scent of old Madeira that practically wafted through the hotel lobby and out the doors to the street. For the founding fathers were passionate admirers of constitutional democracy and fine Madeira, and when the Rare Wine Co’s Mannie Berk throws a Madeira party, it’s an event not to be missed.

Berk had titled the October 8 event “A Trip Through Time: Retracing Madeira’s Journey Across Early America.” “The wines tonight were selected almost exclusively for the story they tell historically,” Berk explained. “I’m as fascinated by the history and connection to America as I am with the wine itself.” Berk co-hosted the event with Vinhos Barbeito’s Ricardo Freitas. Eighteen years ago, Berk faxed Freitas and placed a modest order for some long-unsold inventory: 1,000 cases back to the 18th century. “I was shocked,” Freitas recalled. “I had never shipped old vintages. […] My grandfather and my mother, they had never shipped old vintages.” That original order became the inventory Berk used to start the Rare Wine Co, though those old jewels are much scarcer and more expensive than they used to be.

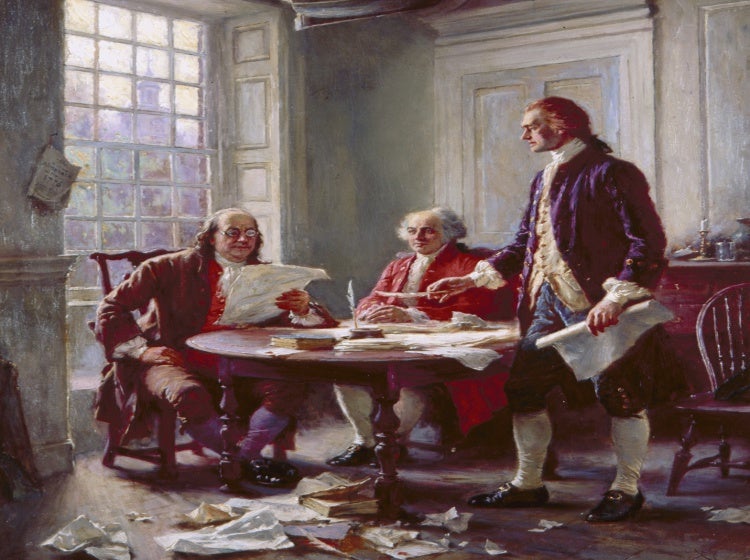

In recent years, Berk and Freitas have collaborated on a series of Madeiras released under the Rare Wine Co Historic Series label. “The way we’ve worked on the Historic Series,” Berk explained, “is that I have this idea of what I want the wine to represent, and then Ricardo makes it. It’s very easy for me.” Some of them, such as the Benjamin Franklin Special Reserve and the Lee Family Stratford Hall Reserve, are named for historical figures with some connection to the style on offer. Others are named for the early American cities in which the style was fashionable. And no wine was more fashionable than Madeira in colonial and early post-independence America — nor, for that matter, more intertwined with America itself. Its rough journey by ship across the Atlantic and subsequent nurturing in cask in stateside cellars was considered essential to forming its character, and anyone who was anyone in American society collected it. In his 1984 book The Island Vineyard, Noël Cossart wrote: “Madeira played such an important part in the American way of life that it was used to toast the Declaration of Independence. Thomas Jefferson used it in July 1792 to toast the decision to locate the US Capitol in Washington, DC, and George Washington’s inauguration in April 1789 at Fraunces Tavern was toasted with Madeira wine. Francis Scott Key composing the ‘Star-Spangled Banner,’ and Betsy Ross sewing the American flag, drank Madeira in 1777.”

The story about the Declaration of Independence was surely apocryphal, Berk admitted, but just as surely true. They toasted everything with Madeira.

One of the better documented examples was on the occasion of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The banquet marking the occasion, as related in David Hancock’s Oceans of Wine, featured four toasts: “the first toast, to the United States and Jefferson, was drunk with Madeira; the second, to Spain and Charles IV, with Malaga and Canary; the third, to France and Napoleon, with pink and white Champagne, and the last, to the ‘eternal happiness of Louisiana,’ with a wine of each drinker’s choosing.” That decision to toast France with French wine, Spain with Spanish wine, and the USA with Madeira, Berk stressed, “tells you that not only did we know that it was our wine, but the rest of the world knew it, too.”

Civil War blend

The vintages poured at the Jefferson Hotel went back to 1821 in the form of a Rainwater Madeira imported by Robert Benson. The “youngest” wine was the newest installment in the RWC Historic Series, the Thomas Jefferson Special Reserve, a blend of nine parts young Verdelho and one part sweet Malvasia from a Barbeito stock over 100 years old. Freitas was in attendance to talk about the Historic Series and two special Madeiras he had drawn from demijohns in his family’s collection to feature in the dinner, the Civil War-vintage 1863 Bual and an 1834 Malvasia vinified, boasted Berk, when Madeira connoisseur John Marshall was still chief justice of the Supreme Court. Cossart reports that Marshall was “famous for his boisterous lawyers’ parties at which Madeira was always drunk, and which kept the Virginia wine merchants prosperous.” But Marshall is best known as the author of Marbury v Madison, in which the Supreme Court resolved a power struggle between the two dominant political parties of the day by ruling against his own Federalist Party — through a chain of reasoning in which he asserted for the court, which the Federalists then controlled, the power to deem laws unconstitutional and strike them down. It was a pyrrhic victory for the newly elected Republican president Thomas Jefferson and eventually recognized as a strategically masterful power grab, “a brilliant example of Chief Justice Marshall’s capacity to sidestep danger while seeming to court it, to advance in one direction while his opponents are looking in another.”

The then secretary of state, James Madison, the respondent in that case, along with John Jay, the court’s first chief justice, and Alexander Hamilton, the country’s first treasury secretary, coauthored the 1787-88 Federalist Papers arguing for the ratification of the Constitution. They signed them anonymously under the name “Publius,” though their collective role in authoring the papers was, according to historian Douglass Adair, “not an especially well-kept secret.” It was whispered about by their friends and officially confirmed with the publication of a French edition in 1792 crediting the work to “Mm Hamilton, Maddisson E Gay, citoyens de l’Etat de New York.” But Madison and Hamilton steadfastly resisted all entreaties to reveal who had written which of the individual papers. Adair attributes this to the fact that they had become bitter political enemies and each found it politically convenient at various times to disclaim interpretations of the Constitution they had previously committed to writing. The authorship of each paper was finally revealed in 1810 as an indirect result of Hamilton’s ill-fated duel with Vice President Aaron Burr. Writes Adair: “Premonitions of death spurred the New Yorker hurriedly to set all of his affairs in order. Among the matters that Hamilton, so typically a man of the 18th century, could not ignore was the judgment that posterity would make of his political career as spokesman for union and interpreter of the United States Constitution. His signature on certain controversial essays, while inconvenient during his life, might well add to his fame if issued posthumously. And so Hamilton stopped by the law office of Egbert Benson two days before his fatal meeting with Burr, and ostentatiously concealed in his friend’s book-case a slip of paper in his own handwriting listing by number the authors of the various essays in The Federalist. After his tragic death the memorandum was discovered as he had planned; nor were well-wishers loath to undertake the commemorative task of making certain his greatness was recognized. In 1810 on the basis of this dramatically planted list, a new edition of The Federalist appeared — the first to attribute […] essays to individual authors.”

Egbert Benson was both a jurist and a founding father who represented New York in the Continental Congress; his nephew Robert was a clerk in his uncle’s law office when Hamilton came to visit, but he later became a prolific Madeira shipper in the March & Benson partnership, which supplied wine to James Madison and his successor in the White House, James Monroe. It’s Robert Benson’s name on the label of the pale 1821 Rainwater served in the Jefferson Hotel on October 8, 2013.

More interesting than delicious?

Mannie Berk had warned in advance that some of the older Madeiras were likely to be more interesting than delicious. The 1821 had an overwhelming stench of nail-polish remover and turpentine that some attendees found disqualifyingly off-putting. But it was not so off-putting to repel anyone from drinking it — which, when you think about it, is itself a rather impressive credit to something poured from a moldy old jug with a mostly unknowable chain of custody going back almost two centuries. The stench was fortunately not a portent of its taste, which was clean and precise and by far the most persistent of all the Madeiras served, reverberating for minutes with flavors of pine-sap and old wood in a fashion almost more reminiscent of a whiskey or other cask-aged spirit than any kind of wine, natural or fortified.

Yet this was a Madeira that would not have spent much time at all in wood. Unlike the typical Bual or Malvasia, whose long residence in cask amplifies the grapes’ sweetness as evaporation does its work, the Rainwater style was bottled young from grapes allowed to ferment mostly dry. With further aging in bottle it becomes bone-dry, as the 1821 was. The general idea was something pale in color and ethereal in its presence. That aspiration was probably best evidenced by another wine from the same era poured together with the 1821, identified only as “Coffin” after the New England family that imported it sometime between 1825 and 1840. It had such a light touch on the palate that it seemed almost, well, watery, but not in the sense of feeling empty or dilute; it simply delivered its flavor subtly and gently, in wisps rather than gushes.

Nobody knows for sure where the Rainwater name came from except that it was certainly of American coinage. The story Berk likes best — if a little too perfect to be true — was that a newly shipped barrel was left on the waterfront with the bunghole open during the rain, and the delicacy of the resulting wine was met with wide approval and came to define a style. Whatever the origin, the Rainwater moniker was once significantly more prestigious than it is now. The Baltimore banker Douglas Thomas, “considered the country’s greatest Madeira connoisseur” in the late 1800s, according to Berk, called Rainwater “the highest standard” of Madeira. Today, Berk noted, most Madeiras sold with the (unregulated) tag Rainwater are innocuous and commercial and bear little resemblance to that once-prized style. He had attempted, with the Baltimore Rainwater in the RWC Historic Series, to fashion an exception — “a recreation of a true Rainwater, the first attempt to make a genuine Rainwater in the last century.” The result actually did bear a striking resemblance to the 1821 and the Coffin, similarly complexioned with that same piney and whiskey-like woodiness, but without any of the alcoholic stiffness of a spirit.

This was not a coincidence. Berk had shipped Freitas a sample of the 1821, and Freitas used that wine as his model in creating the Baltimore Rainwater blend. “It took more than one year of discussions trying to reach the ideal blend to replicate the 1821,” Freitas said. “The Baltimore was the closest I could reach.” He began considering grape varieties produced in big quantities in the early 19th century and settled on Verdelho as the basis for the blend, adding Sercial to bring the result closer to the desired level of dryness. Freitas also noted that a key attribute of the 1821 was that the oxidation level is much lower than the modern norm for Madeira. The Verdelho and Sercial together were too oxidized, so Freitas did “something completely unthinkable” to bring down the oxidation level — he added one-year-old wine. Yet the blend was still missing something, and Freitas had a puzzle at hand: how to find something developed enough to instill the necessary character without negating everything he had done before to achieve the levels of sweetness, oxidation, and weight he was aiming for. The solution came in the form of 250 liters he found of 20-year-old Tinta Negra — “aged, but not oxidized, because it had been aged in a stainless-steel tank.”

The final parameters for the wine were so dangerously atypical for the appellation that Freitas feared it might not be approved for sale by the authorities. But the comparison with the Benson and Coffin leaves little room to doubt that it was typical of what was sold in the early 1800s. While it lacked the endlessly persistent finish that only age can deliver, the uncanny similarity in their flavors and structural profile made the case for Freitas as a master blender.

The difference between a master blender and a random blender was, in fact, demonstrated somewhat evocatively by one of the other bottles opened — a bottling of the leftovers of a dozen old Madeiras opened at a Rare Wine Co dinner held in New York in 1999. The oldest of those was from 1802, and if it seems like sacrilege to pour them all together in an indiscriminate brew, Berk had explained that it was a common feature of 19th-century Madeira parties “to make a toast, using a blend (called the ‘lees’) of all the Madeiras drunk at a previous Madeira party.” In this case, the result was perfectly agreeable but also muddled and anonymous, lacking the identifiable style and character that distinguished the other wines.

Perhaps its company put it at a disadvantage, because it was preceded by the 1863 Bual and the 1834 Malvasia, which silenced the room. Both had aged to a Port-like complexion, the Bual throwing off one of those packed aromas that keeps one’s nose in the glass for ages before it even becomes necessary to venture a sip. On the palate, it seemed to ooze with the nectar of exotic sun-dried fruits reminiscent of some hybrid of cranberry and fig, though its alcoholic strength left the finish a bit spirity. The Malvasia, however, amplified the fruit density to such a level that the alcohol was completely masked. It was instantly palate-coating with similar sun-dried flavors but an octave deeper in tone, and slick and glossy as it went down the gullet.

What impressed me the most, however, was how well many of the RWC Historic Series Madeiras acquitted themselves beside these legends. Two of them were particular standouts and among the highlights of the evening. The first, called The Wanderer, after a ship used to carry Madeira and other goods to New York in the 1800s, certainly did justice to the “Rare Wine” label because only 60 bottles were made. It was drawn in 2006 from a demijohn of Tinta Negro believed to have been vintaged in the 1940s or 1950s. The wine had a blonde, grainy complexion but the longer it sat in the mouth, the deeper the flavors became, with an expansive palate coverage. It was compelling not just in its own right but as a demonstration of an underappreciated fact about Madeira: that though it may be virtually indestructible, it is not static. In the first few years after the Wanderer’s bottling, Freitas admitted, he didn’t much like it. But now it exhibited a very forceful personality, as indeed it had before Freitas made the decision to preserve it as its own wine instead of a component in a blend. He corrected the common misapprehension that Madeira once out of its cask remains in a state of suspended animation. It evolves both in bottle and in demijohns, the latter of which he considers not so much a holding pen but a tool in the winemaking process, allowing some oxidative flavor development (because they are not necessarily filled to the brim) without the evaporation and thickening of the body that occurs in cask.

Freitas thinks that the newest Historic Series offering, the Thomas Jefferson Special Reserve, could turn out to be the best he has made. It actually has a more direct connection to Jefferson than any of the famously fraudulent “Th.J.” clarets purported to have come from his cellar. A 29-year-old Jefferson wrote in 1773 that “[M]rs. Wythe” — the wife of George Wythe, mentor in law to both Jefferson and John Marshall — “puts 1/10 very rich superfine Malmesey to a dry Medeira and makes a fine wine.” Decades later, he described four “terms by which we characterise different qualities of wines,” including “sweet wines,” “acid wines,” “dry wines,” and finally “silky wines, which are in truth a compound in their taste of the dry wine dashed with a little sweetness, barely sensible to the palate: the silky Madeira which we sometimes get here, is made so by putting a small portion of Malmsey into dry Madeira.” The Jefferson Special Reserve recreates the Wythe blend in grand fashion: The one part sweet Malmsey is from a stock over 100 years old; the remainder is younger dry Verdelho. The result seemed to me an eerily accurate recreation of what the wine Jefferson drank must have tasted like, because “silky” is the very first word that came to my mind on tasting it. It had a sheen to it but with added textural intrigue reminiscent of the lacy tannic knit of a fine red Burgundy. The admixture of the young Verdelho with the century-old Malmsey gave the wine a tensile spine and an intricate complexity combining fresh citrus notes with deeper, darker tones encompassing steeped orange-peel, mulling spices, and some of the flavors of old brandy. Jefferson surely would have approved.

Restoration of Madeira

Writing in Federalist no.58 in 1788, James Madison offered his prediction that in any standoff among the branches of government, the House of Representatives was likely to prevail. The House’s ability to “refuse […] the supplies requisite for the support of government,” Madison wrote, “may, in fact, be regarded as the most complete and effectual weapon with which any constitution can arm the immediate representatives of the people, for obtaining a redress of every grievance.” He dismissed the idea that the House would be “first to yield” in a “trial of firmness,” figuring that “[t]he utmost degree of firmness that can be displayed by the federal Senate or President will not be more than equal to a resistance” grounded in the House’s “power over the purse.”

Madison got it wrong. On October 17, 2013, the House of Representatives caved to the demands of US President Barack Obama and the Democratically controlled Senate and passed a bill unconditionally restoring funding to the government. They did not toast the agreement with anything so memorable as Madeira, however. On the eve of the deal, an Associated Press photographer captured a Congressional aide making a delivery of several dozen pizzas to the office of Speaker of the House John Boehner, where leaders of the two warring parties were huddled in negotiations. No doubt they were accompanied by copious caffeinated soda. History demonstrates that partisan politics was just as ruthless when our “government of laws and not of men” was administered by men of Madeira rather than men of pizza and Coke, but it was, at the very least, rather more dignified. At the Jefferson Hotel, Freitas proposed a toast: “The restoration of Madeira in this country is a reality, because of Mannie Berk.” Perhaps there is hope for America yet.